Phishers abused Google Sites and DKIM replay to send valid-signed emails, bypassing filters and stealing credentials.

Microsoft on Monday announced that it has moved the Microsoft Account (MSA) signing service to Azure confidential virtual machines (VMs) and that it’s also in the process of migrating the Entra ID signing service as well.

The disclosure comes about seven months after the tech giant said it completed updates to Microsoft Entra ID and MS for both public and United States government clouds to generate, store, and automatically rotate access token signing keys using the Azure Managed Hardware Security Module (HSM) service.

“Each of these improvements helps mitigate the attack vectors that we suspect the actor used in the 2023 Storm-0558 attack on Microsoft,” Charlie Bell, Executive Vice President for Microsoft Security, said in a post shared with The Hacker News ahead of publication.

Microsoft has released the optional KB5055612 preview cumulative update for Windows 10 22H2 with two changes, including a fix for a GPU paravirtualization bug in Windows Subsystem for Linux 2 (WSL2).

The KB5055612 cumulative update preview is part of Microsoft’s “optional non-security preview updates” schedule, typically released at the end of every month. This update allows Windows admins to test upcoming fixes and features that will be released in the upcoming May Patch Tuesday.

Unlike Patch Tuesday cumulative updates, this preview update does not include security updates.

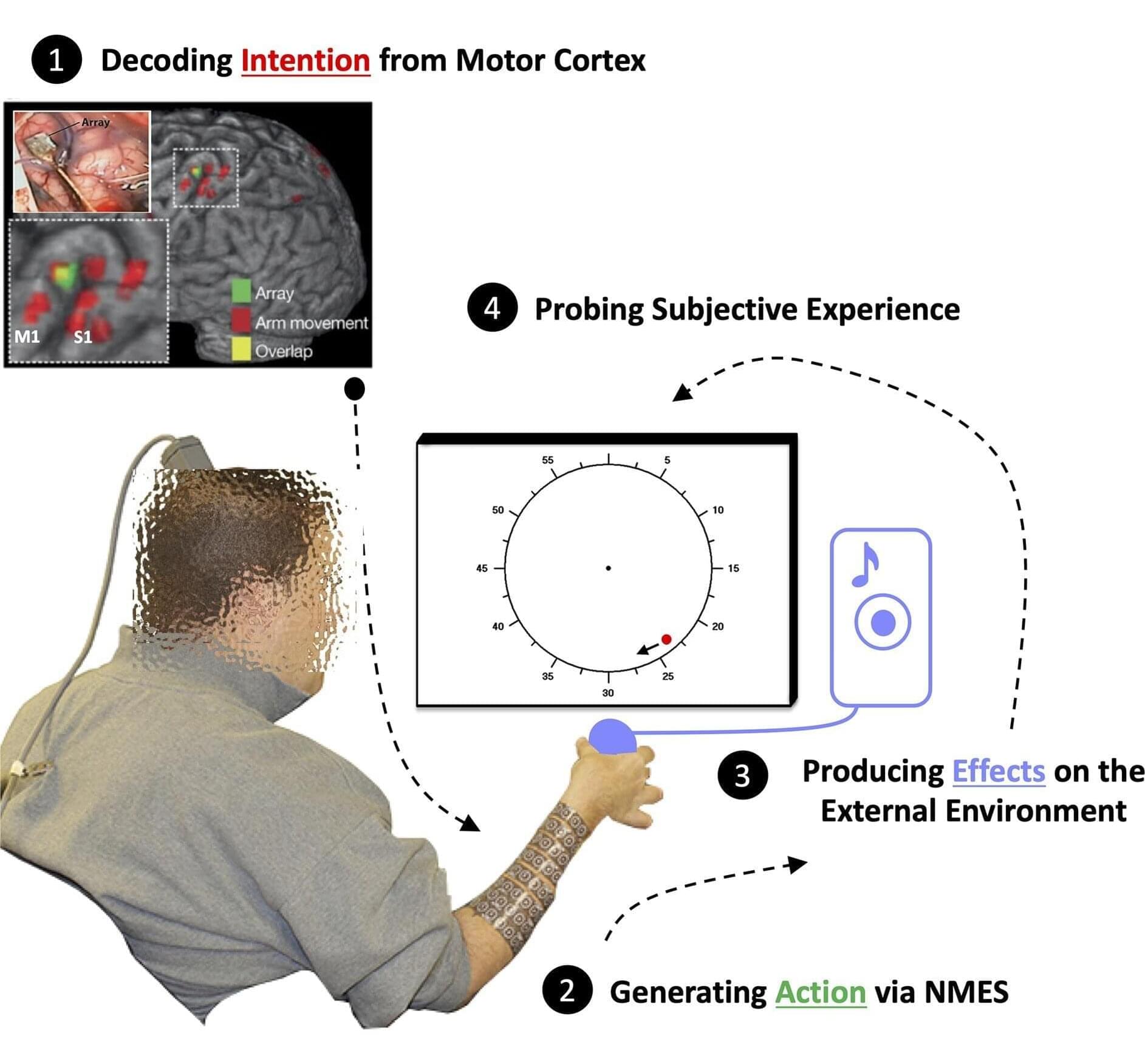

Researchers led by Jean-Paul Noel at the University of Minnesota, United States, have decoupled intentions, actions and their effects by manipulating the brain-machine interface that allows a person with otherwise paralyzed arms and legs to squeeze a ball when they want to.

Published in the open-access journal PLOS Biology, the study reveals temporal binding between intentions and actions, which makes actions seem to happen faster when they are intentional.

Separating intentions from actions was made possible because of a brain-machine interface. The participant was paralyzed with damage to their C4/C5 vertebrae and had 96 electrodes implanted in the hand region of their motor cortex.

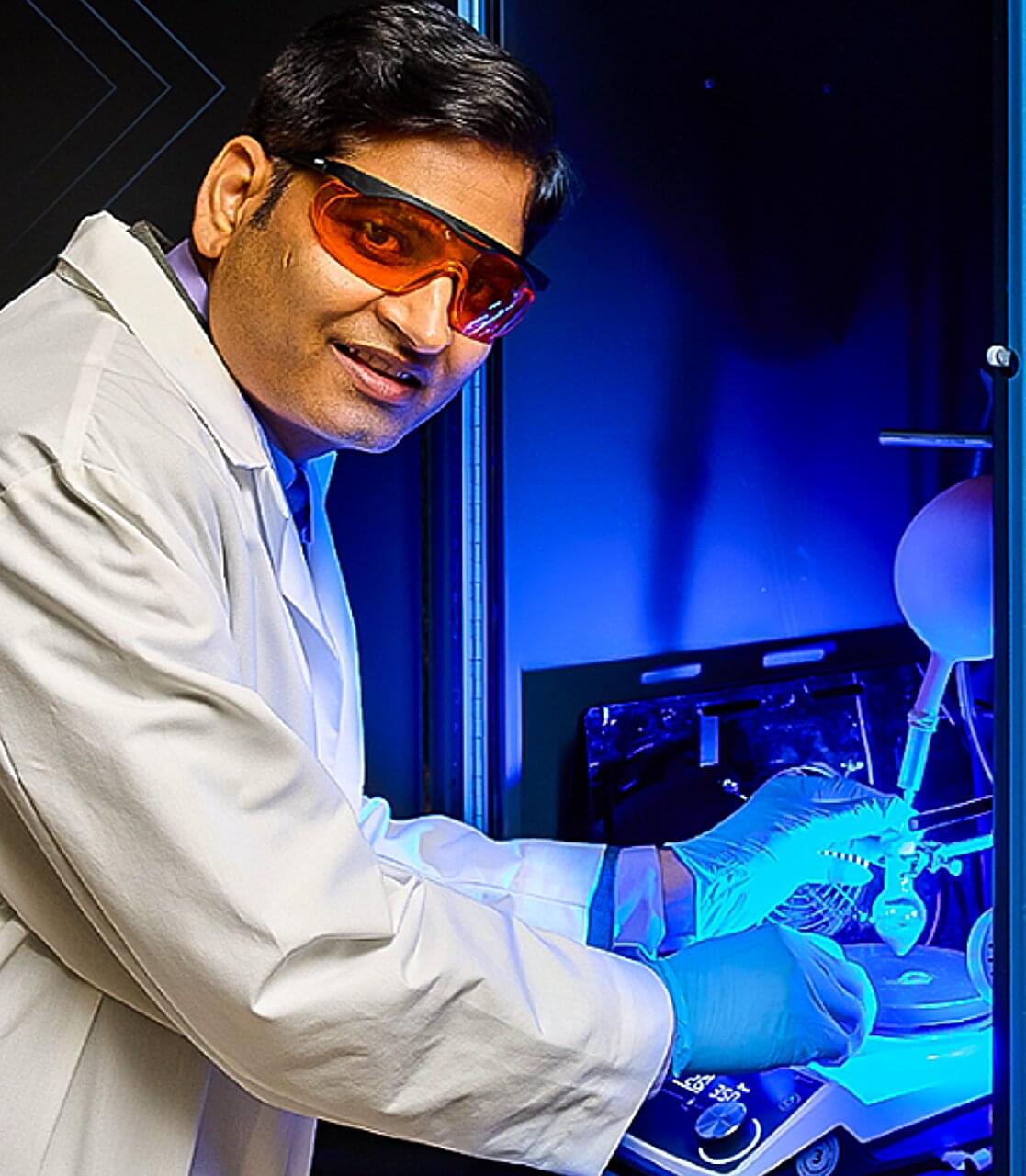

Researchers at the University of Oklahoma have made a discovery that could potentially revolutionize treatments for antibiotic-resistant infections, cancer and other challenging gram-negative pathogens without relying on precious metals.

Currently, precious metals like platinum and rhodium are used to create synthetic carbohydrates, which are vital components of many approved antibiotics used to combat gram-negative pathogens, including Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a notorious hospital-acquired infection responsible for the deaths of immunocompromised patients. However, these elements require harsh reaction conditions, are expensive to use and are harmful to the environment when mined.

In an innovative study published in the journal Nature Communications, an OU team led by Professor Indrajeet Sharma has replaced these precious metals with either blue light or iron, achieving similar results with significantly lower toxicity, reduced costs, and greater appeal for researchers and drug manufacturers.

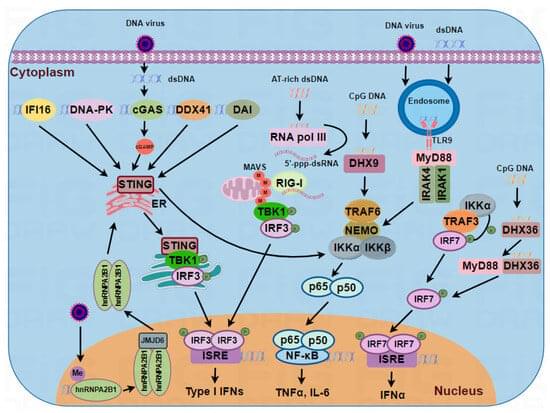

During viral infection, the innate immune system utilizes a variety of specific intracellular sensors to detect virus-derived nucleic acids and activate a series of cellular signaling cascades that produce type I IFNs and proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines. Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) is an oncogenic double-stranded DNA virus that has been associated with a variety of human malignancies, including Kaposi’s sarcoma, primary effusion lymphoma, and multicentric Castleman disease. Infection with KSHV activates various DNA sensors, including cGAS, STING, IFI16, and DExD/H-box helicases. Activation of these DNA sensors induces the innate immune response to antagonize the virus. To counteract this, KSHV has developed countless strategies to evade or inhibit DNA sensing and facilitate its own infection. This review summarizes the major DNA-triggered sensing signaling pathways and details the current knowledge of DNA-sensing mechanisms involved in KSHV infection, as well as how KSHV evades antiviral signaling pathways to successfully establish latent infection and undergo lytic reactivation.

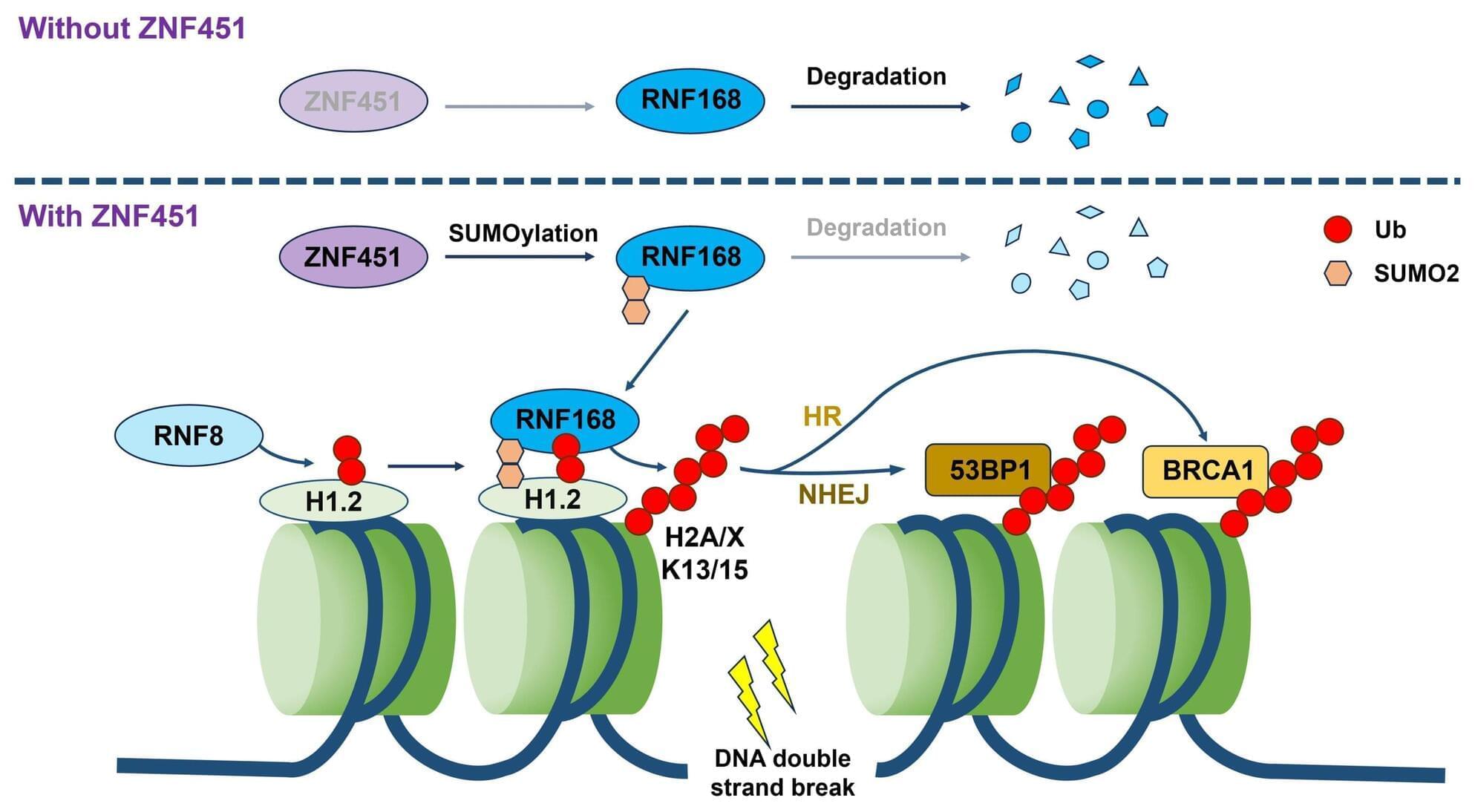

A research team has unveiled a crucial mechanism that helps regulate DNA damage repair, with important implications for improving cancer treatment outcomes.

The result was published in Cell Death & Differentiation. The team was led by Professor Zhao Guoping at the Hefei Institutes of Physical Science of the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

The efficacy of radiotherapy is largely limited by the DNA damage repair capacity of tumor cells. When ionizing radiation induces DNA double-strand breaks—the primary lethal damage—tumor cells often exhibit abnormal overexpression of DNA repair proteins, establishing a robust damage response system that drives clinical radioresistance. To address this challenge, the team deciphered the regulatory network of epigenetic modifications in DNA damage repair.

But classic risk factors do not seem to fully explain the recent rise in early-onset cancers, says Dr. Cathy Eng, director of the Young Adult Cancers Program at Vanderbilt University’s Ingram Cancer Center in Tennessee. Some of the trends are baffling; young, nonsmoking women, for example, are being diagnosed with lung cancer in strangely high numbers. Many times, Eng’s patients were extremely healthy: vegetarians, marathon runners, avid swimmers. “That’s why I really believe there’s other risk factors to account for this,” she says.

There’s no shortage of theories about what those may be. Many scientists point to modern diets, which tend to be heavy on potentially carcinogenic products—including ultra-processed foods, red meat, and alcohol—and may also contribute to weight gain, another cancer risk factor. The foods we eat can also affect the gut microbiome, the colony of microbes that lives in the digestive system and appears linked to overall health. Alterations to the gut microbiome via diet, or perhaps exposure to drugs like antibiotics, have also been implicated.

Other researchers blame the microplastics littering our environment and leaching into our food and water supplies, some of which, according to a 2024 study, have even shown up in cancer patients’ tumors. Other environmental factors could also be to blame, given that everything from cosmetics to food packaging contains substances that many researchers aren’t convinced are safe. Even our near constant exposure to artificial light could be messing with normal biological rhythms in ways that have profound health consequences, some research suggests.

The electric skin cell signals, which move at glacial pace compared to those in nerve cells, may play a role in initiating healing.

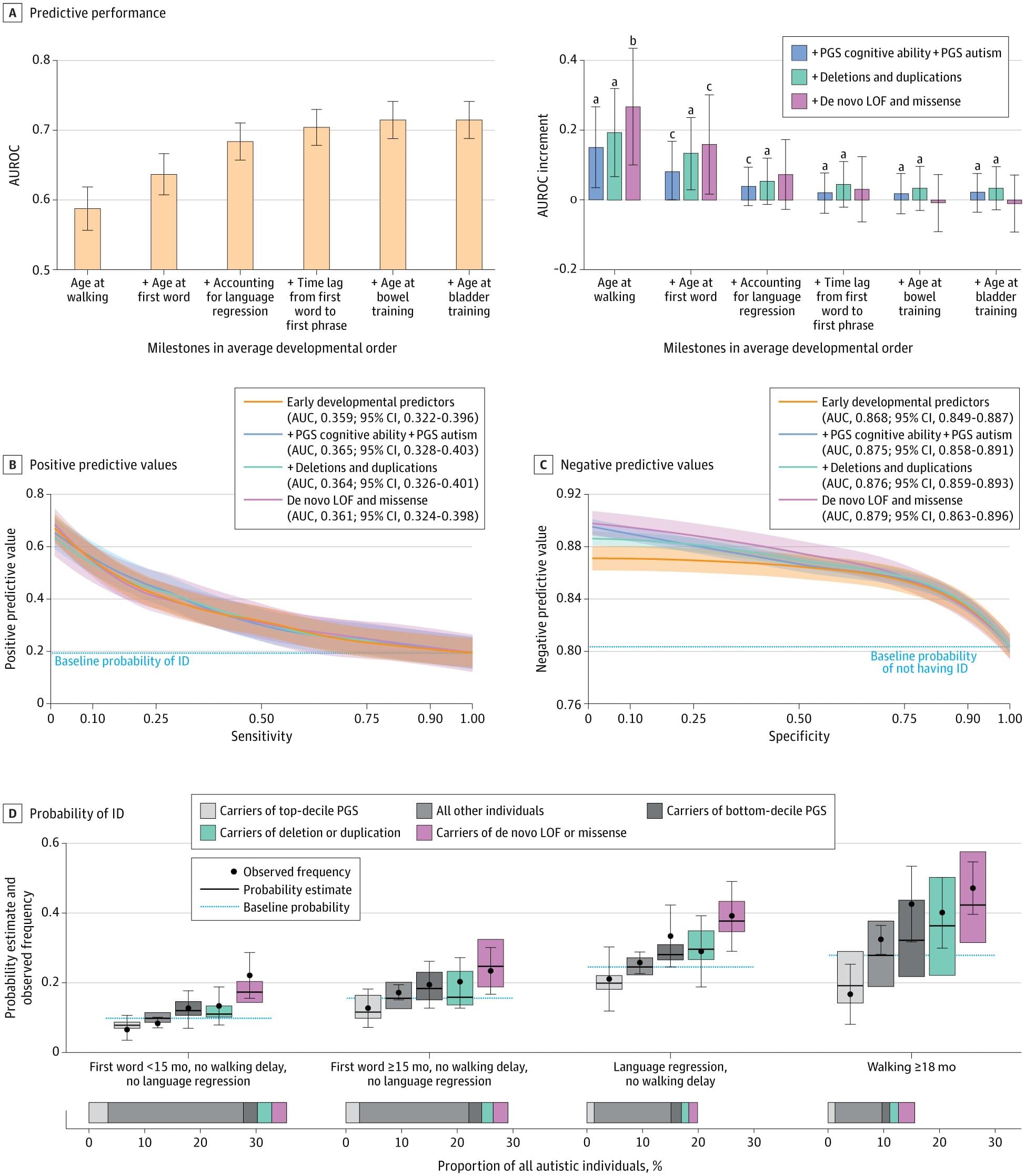

Will a child who’s evaluated for autism later develop an intellectual disability? Can this be accurately predicted? Early-childhood experts in Quebec say they’ve have come up with a better way to find out.

In a study of 5,633 children drawn from three North American cohorts, clinician-researchers affiliated with Université de Montréal developed a new predictive model that combines a wide range of genetic variants with data on each stage of a young child’s development.

Their goal? To obtain reliable information as early as possible to predict the children’s developmental trajectory and thus offer more proactive support to those who may need it—namely, parents trying to better understand and anticipate their child’s needs.