Experiments with membranes offer a path toward scalable neuromorphic computing.

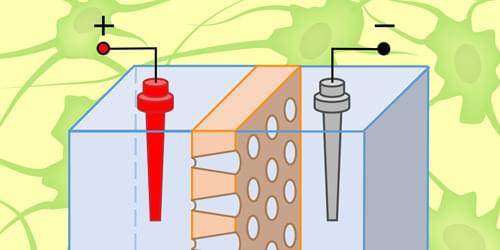

Imagine a future in which computers process information not with streams of electrons but with hydrated ions flowing through salt water, a system that mimics how the brain itself computes. This emerging field—known as iontronics, a portmanteau of ions and electronics—is rapidly growing as researchers design neuromorphic computing devices, inspired by animal nervous systems and powered by electrolyte solutions at the nanoscale [1–3]. Since Leon Chua introduced the memory resistor or “memristor” in the 1970s [4], these components have been considered revolutionary building blocks for neuromorphic computing. A memristor’s electrical resistance depends on the current that flowed through it before it was powered off, offering a way to store information. Unlike solid-state memristors, fluidic ones still face challenges in terms of scalability and integration with a circuit.