Fermi Inc. has signed deals to begin production of four big nuclear-power reactors that would be used for a private data center grid campus in the Texas Panhandle.

King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST; Saudi Arabia) researchers have set a record in microchip design, achieving the first six-stack hybrid CMOS (complementary metal-oxide semiconductor) for large-area electronics. With no other reported hybrid CMOS exceeding two stacks, the feat marks a new benchmark in integration density and efficiency, opening possibilities in electronic miniaturization and performance.

A paper detailing the team’s research appears in Nature Electronics.

Among microchip technologies, CMOS microchips are found in nearly all electronics, from phones and televisions to satellites and medical devices. Compared with conventional silicon chips, hybrid CMOS microchips hold greater promise for large-area electronics. Electronic miniaturization is crucial for flexible electronics, smart health, and the Internet of Things, but current design approaches are reaching their limits.

Title: The Shaw Prize Lecture in Mathematics 2025: From Shape to Space.

Date: Oct 22, 2025

Speaker: Prof. Kenji FUKAYA

Please go to our webpage for more IAS Events:

Like humans, artificial intelligence learns by trial and error, but traditionally, it requires humans to set the ball rolling by designing the algorithms and rules that govern the learning process. However, as AI technology advances, machines are increasingly doing things themselves. An example is a new AI system developed by researchers that invented its own way to learn, resulting in an algorithm that outperformed human-designed algorithms on a series of complex tasks.

For decades, human engineers have designed the algorithms that agents use to learn, especially reinforcement learning (RL), where an AI learns by receiving rewards for successful actions. While learning comes naturally to humans and animals, thanks to millions of years of evolution, it has to be explicitly taught to AI. This process is often slow and laborious and is ultimately limited by human intuition.

Taking their cue from evolution, which is a random trial and error process, the researchers created a large digital population of AI agents. These agents tried to solve numerous tasks in many different, complex environments using a particular learning rule.

Wearable or implantable devices to monitor biological activities, such as heart rate, are useful, but they are typically made of metals, silicon, plastic and glass and must be surgically implanted. A research team in the McKelvey School of Engineering at Washington University in St. Louis is developing bioelectronic hydrogels that could one day replace existing devices and have much more flexibility.

Alexandra Rutz, an assistant professor of biomedical engineering, and Anna Goestenkors, a fifth-year doctoral student in Rutz’s lab, created novel granular hydrogels. They are made of microparticles that could be injected into the body, spread over tissues or used to encapsulate cells and tissue and also to monitor and stimulate biological activity. Results of their research were published Oct. 8 in the journal Small.

The microparticles are spherical hydrogels made from the conducting polymer known as PEDOT: PSS. When packed tightly, they are similar to wet sand or paste: They hold as a solid with micropores, but they can also be 3D printed or spread into different shapes while maintaining their structure or redistributed into individual microparticles when placed in liquid.

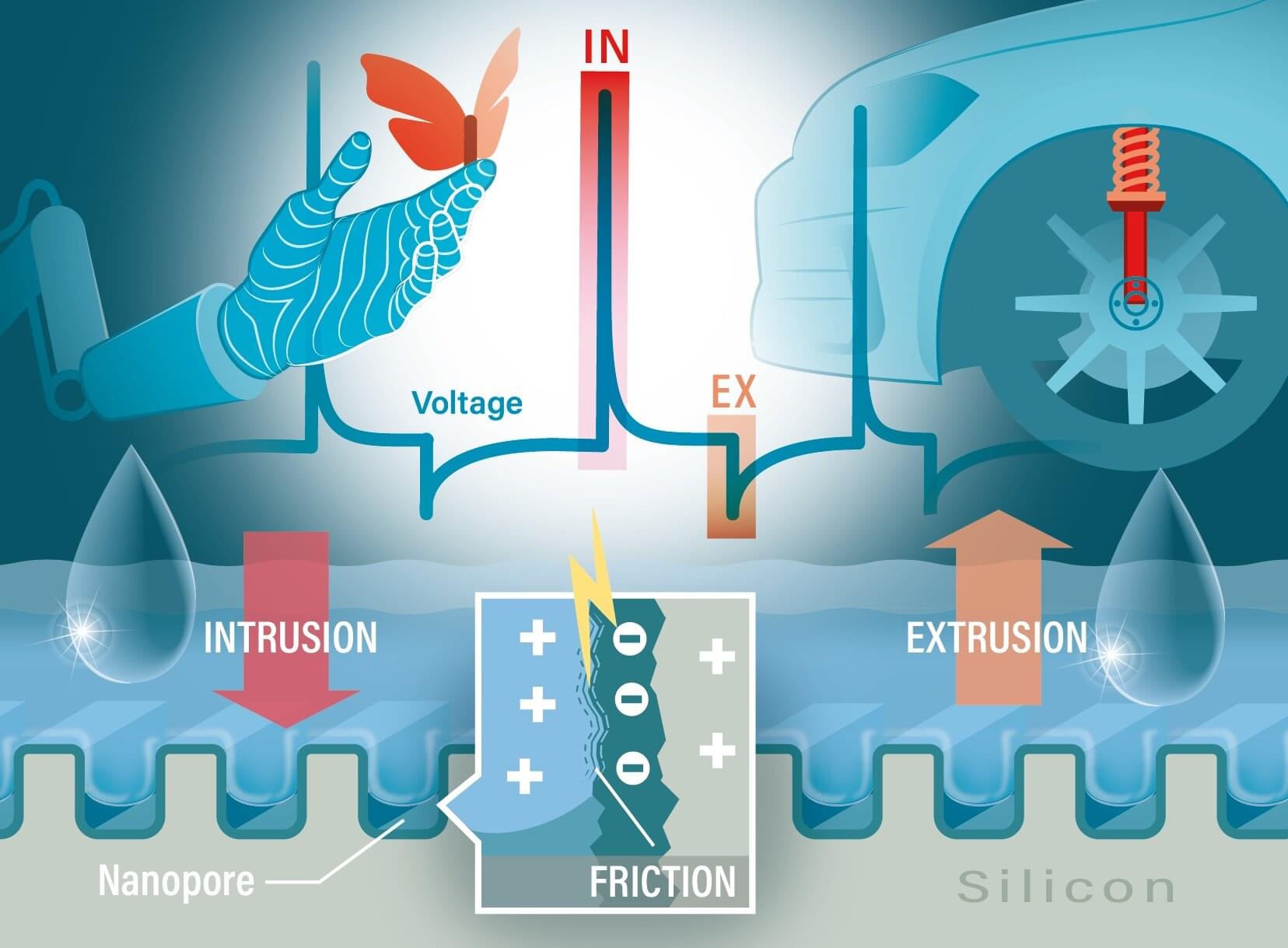

A European research team involving Hamburg University of Technology (TUHH) and Deutsches Elektronen-Synchrotron DESY has developed a novel way for converting mechanical energy into electricity—by using water confined in nanometer-sized pores of silicon as the active working fluid.

In a study published in Nano Energy, scientists from CIC energiGUNE (Spain), the University of Ferrara (Italy), the Hamburg University of Technology (TUHH) and DESY (Germany), the University of Silesia in Katowice (Poland), and Riga Technical University (Latvia), demonstrate that the cyclic intrusion and extrusion of water in water-repellent nanoporous silicon monoliths can produce measurable electrical power.

Scientists from the A*STAR Infectious Diseases Labs (A*STAR IDL) have uncovered a surprising mechanism showing how mosquito saliva can alter the human body’s immune response during chikungunya virus (CHIKV) infection, contributing to Singapore’s broader efforts to strengthen infectious disease preparedness.

The research, published in Nature Communications, reveals that sialokinin, a bioactive peptide in Aedes mosquito saliva, binds to neurokinin receptors on immune cells and suppresses monocyte activation, thereby reducing inflammation and facilitating early viral dissemination. These findings offer new insight into how mosquito bites shape disease outcomes.

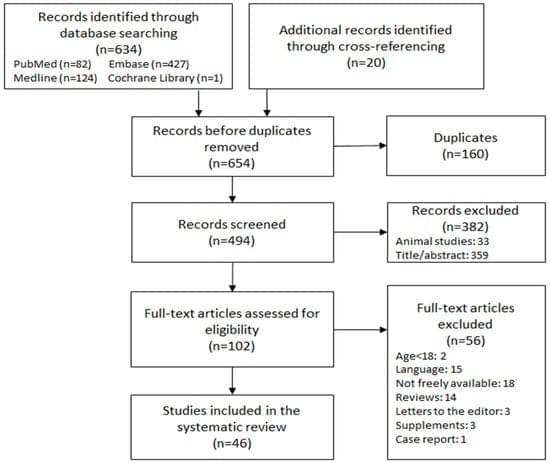

Background: acute mesenteric ischemia (AMI) is a life-threatening condition that is caused by inadequate blood flow through the mesenteric vessel and is related to high mortality rates due to systemic complications. This study aims to systematically review the available literature concerning the major findings of possible biomarkers for early detection of acute mesenteric ischemia in the human population. Methods: studies that measured the performance of biomarkers during acute mesenteric ischemia were identified with the search of PubMed, Embase, Medline, and Cochrane library. Results: from a total of 654 articles, 46 articles examining 14 different biomarkers were filtered, falling within our inclusion criteria. Intestinal fatty acid-binding protein (I-FABP) was the most commonly researched biomarker regarding AMI, with sensitivity ranging from 61.5% to 100% and specificity ranging from 40% to 100%. The second most commonly researched biomarker was D-dimer, with a sensitivity of 60–100% and a specificity of 18–85.71%. L-lactate had a sensitivity of 36.6–90.91% and a specificity of 64.29–96%. Several parameters within the blood count were examined as potential markers for AMI, including NLR, PLR, MPV, RDW, DNI, and IG. Citrulline, interleukin 6 (IL-6), and procalcitonin (PCT) were the least-researched biomarkers. Conclusion: different biomarkers showed different accuracies in detecting AMI. I-FABP and D-dimer have been the most researched and shown to be valuable in the diagnosis of AMI, whereas L-lactate could be used as an additional tool. Ischemia-modified albumin (IMA), alpha glutathione S-transferase (αGST), interleukin 6 (IL-6), and citrulline showed potential use in their respective studies. However, further research needs to be done on larger sample sizes and with controls to reduce bias. Several studies showed that neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio (NLR), platelet–lymphocyte ratio (PLR), mean platelet volume (MPV), red-cell distribution width (RDW), delta neutrophil index (DNI), and immature granulocytes (IGs) might be useful, as well at the same time be widely distributed and affordable in combination with other markers presenting higher specificity and sensitivity.