Scientists have turned brain cells into tiny light sources, revealing the brain at work like never before.

Get the latest international news and world events from around the world.

Darwin Gödel Machine Explained: Self-Improving AI Agents

In this video, we dive into Darwin Gödel Machine (DGM), introduced in a recent paper from Sakana AI and the University of British Columbia.

Darwin Gödel Machine takes self-improving AI a step froward, by introducing a mechanism for an AI agent to self-improve itself.

Paper — https://arxiv.org/abs/2505.22954

Written Review — https://aipapersacademy.com/darwin-go… 🔔 Subscribe for more AI paper reviews! 📩 Join the newsletter → https://aipapersacademy.com/newsletter/ Patreon — / aipapersacademy The video was edited using VideoScribe — https://tidd.ly/44TZEiX ___________________ Chapters: 0:00 Introduction 1:54 Darwin Gödel Machine 3:59 Results.

___________________

🔔 Subscribe for more AI paper reviews!

📩 Join the newsletter → https://aipapersacademy.com/newsletter/

Patreon — / aipapersacademy.

The video was edited using VideoScribe — https://tidd.ly/44TZEiX

Ubiquitous Subjectivity: A Whiteheadian Philosophy of Mind

Home.

Process Worldview.

Community.

Art and Music.

Whitehead and Process Thinking.

String Theory in 2037 | Brian Greene & Edward Witten

Edward Witten, widely regarded as one of the greatest living theoretical physicists, sits down with Brian Greene to explore the deepest questions at the frontiers of modern science. From string theory and quantum gravity to black holes, cosmology, and the nature of consciousness, Witten reflects on what physics has revealed—and what remains profoundly mysterious.

The only physicist to receive the Fields Medal, Witten discusses why unifying quantum mechanics and general relativity has proven so difficult, how string theory forces gravity into its framework, and why decades of progress have still not revealed the fundamental principles underlying the theory. He also examines powerful ideas such as duality, extra dimensions, and the controversial anthropic principle, offering rare insight into how physicists grapple with uncertainty at the edge of human understanding.

The conversation moves beyond equations into philosophy, addressing questions about free will, the quantum measurement problem, and whether consciousness plays a role in how reality is observed. Witten reflects candidly on discovery, doubt, beauty in mathematics, and what it feels like to work at the limits of knowledge.

This discussion is essential viewing for anyone interested in theoretical physics, cosmology, quantum theory, and the future of our understanding of the universe.

This program is part of the Rethinking Reality series, supported by the John Templeton Foundation.

Participant: Edward Witten.

Moderator: Brian Greene.

0:00:00 — Introduction: Free Will, Physics, and the Quest to Unify Reality.

Space travel will radically change human psychology and spirituality

It may cause us to geneticly engineer ourselves to live in dangerous environments too.

Throughout human history, we have associated our spirituality, myths, and religions with the sky. Constellations are peppered with sky stories, from Orion to Warepil (the eagle constellation of aboriginal Australians). The Lakota Native Americans associated the Milky Way as a path for departed souls. Jesus ascended to the heavens. The primary god of ancient Egyptians was Ra, the god of the Sun. And the entire Universe was seen inside Krishna’s mouth.

Jason Batt, a science fiction author, mythologist, and futurist, has spent a lot of time thinking about stories like this, and how our relationship with the heavens will change when we become a space-faring race. “So what happens to humanity?” Batt, who is also a co-founder of Deep Space Predictive Research Group and a Creative Manager of 100 Year Starship, pondered while speaking to Big Think. “What is going to change in us? What is going to transform?”

Even though we often associate our space travel with feats of engineering and science, there is an undeniable connection with our myth as well. We see this in how we name our rockets destined for space: Gemini, Apollo, Artemis. Going to space is big, not just for our technology, but for our spirits.

KFSHRC Uses AI Enabled Brain Implants in Advanced Neurological Care

The device is also used in selected neurological cases where accurate signal detection and responsive stimulation are critical to managing symptoms over time. Its application forms part of a broader treatment pathway rather than a standalone intervention.

Implantation is performed using minimally invasive techniques and typically takes three to five hours. The approach avoids large surgical incisions and supports shorter recovery periods, allowing patients to resume daily activities more quickly.

Rather than marking a single milestone, the continued use of this technology reflects KFSHRC’s integration of artificial intelligence into routine neurological care, where adaptability and long-term management are central to patient outcomes.

RIYADH, SAUDI ARABIA, December 28, 2025 /EINPresswire.com/ — At King Faisal Specialist Hospital & Research Centre (KFSHRC) in Riyadh, artificial intelligence enabled brain implants are used as part of advanced care for patients with neurological conditions, including Parkinson’s disease and selected movement disorders.

The implant functions by continuously analyzing brain signals and responding to abnormal activity through targeted electrical stimulation. This adaptive approach allows treatment to adjust in real time based on the patient’s neural patterns, reducing reliance on fixed stimulation settings and limiting the need for frequent manual recalibration.

In clinical practice, the technology has supported improved symptom control for patients whose conditions require precise neuromodulation. As treatment progresses, some patients have been able to reduce their dependence on medication under clinical supervision, while maintaining daily function and stability.

Alexander Grothendieck

You deserve an explanation, so please don’t skip this 1-minute read. It’s Sunday, December 28. Our fundraiser will soon be over, but fewer people are seeing our message this December and we’re short of our goal. If you’ve lost count of how many times you’ve visited Wikipedia this year, we hope that means it’s given you at least $2.75 of knowledge. If everyone who finds Wikipedia useful gave $2.75, we’d hit our goal in a few hours.

It’s been 25 years and Wikipedia is still free. It’s still created by people, not machines, and we don’t run ads or put up paywalls because we’re not here to make a profit off your attention. In other words, it’s still the internet we were promised.

Less than 2% of our readers donate, so if you’ve never given and Wikipedia has provided you with at least $2.75 worth of knowledge, donate today. If you are undecided, remember any contribution helps.

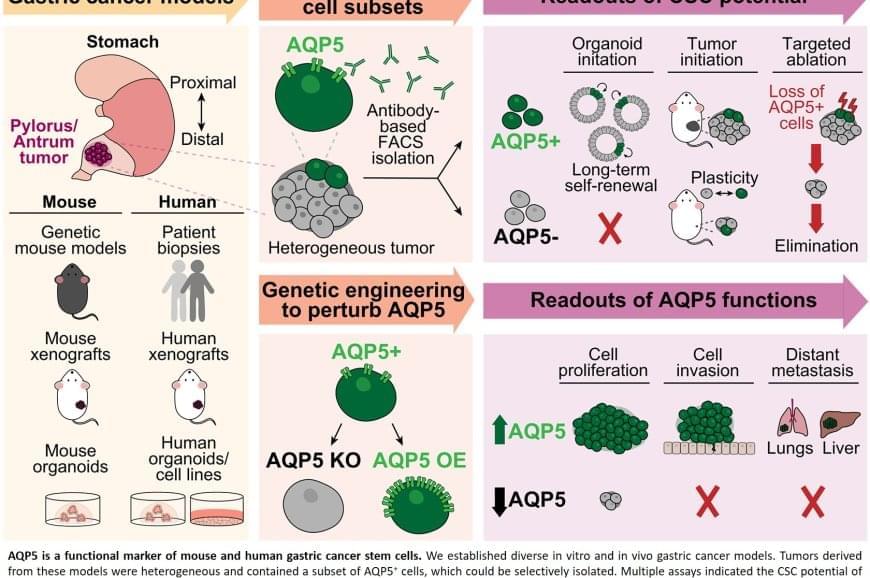

Aquaporins in cancer stem cells targeted to prevent gastric cancer recurrence

Scientists have long suspected that a small population of cells survives treatment and regenerates the tumor. These “cancer stem cells” are thought to resist conventional therapies, allowing the disease to return even after the visible tumor has been removed.

Previous attempts to identify gastric cancer stem cells using other protein markers, such as CD44 or CD133, yielded inconsistent results. These markers often appeared on healthy cells as well or did not fully account for tumor behaviour.

The team discovered that AQP5 reliably marks the cancer stem cells in gastric tumors. Aquaporins are proteins that form channels in cell membranes to control the movement of water into and out of cells. While AQP5 was previously known to mark stem cells in healthy gastric tissue, this study shows it also identifies the specific cells responsible for driving tumor growth, spread, and recurrence.

Importantly, AQP5 does more than simply mark these cells; it actively contributes to their aggressive behavior.

The researchers found that cells with AQP5 were capable of forming new tumors, while cells without AQP5 rarely did so. Most significantly, when they used a targeted method to eliminate only the AQP5-expressing cells, tumors stopped growing or shrank entirely and did not recur. This held true even for cancers that had spread to other organs.

Scientists have identified the specific cells responsible for gastric cancer’s tendency to return after treatment. The study also demonstrated that eliminating these cells stops tumors from growing, even in advanced disease that has spread to other organs.

Machine learning helps robots see clearly in total darkness using infrared

From disaster zones to underground tunnels, robots are increasingly being sent where humans cannot safely go. But many of these environments lack natural or artificial light, making it difficult for robotic systems, which usually rely on cameras and vision algorithms, to operate effectively.

A team consisting of Nathan Shankar, Professor Hujun Yin and Dr. Pawel Ladosz from The University of Manchester is tackling this challenge by teaching robots to “see” in the dark. Their approach uses machine learning to reconstruct clear images from infrared cameras—sensors that can “see” even when no visible light is present.

The breakthrough, published in a paper on the arXiv preprint server, means that robots can continue using their existing vision algorithms without making changes, reducing both computational costs and the time it takes to deploy them in the field.