Imagine you are a security guard in one of those casino heist movies where your ability to recognize an emerging crime will depend on whether you notice a subtle change on one of the many security monitors arrayed on your desk. That’s a challenge of visual working memory.

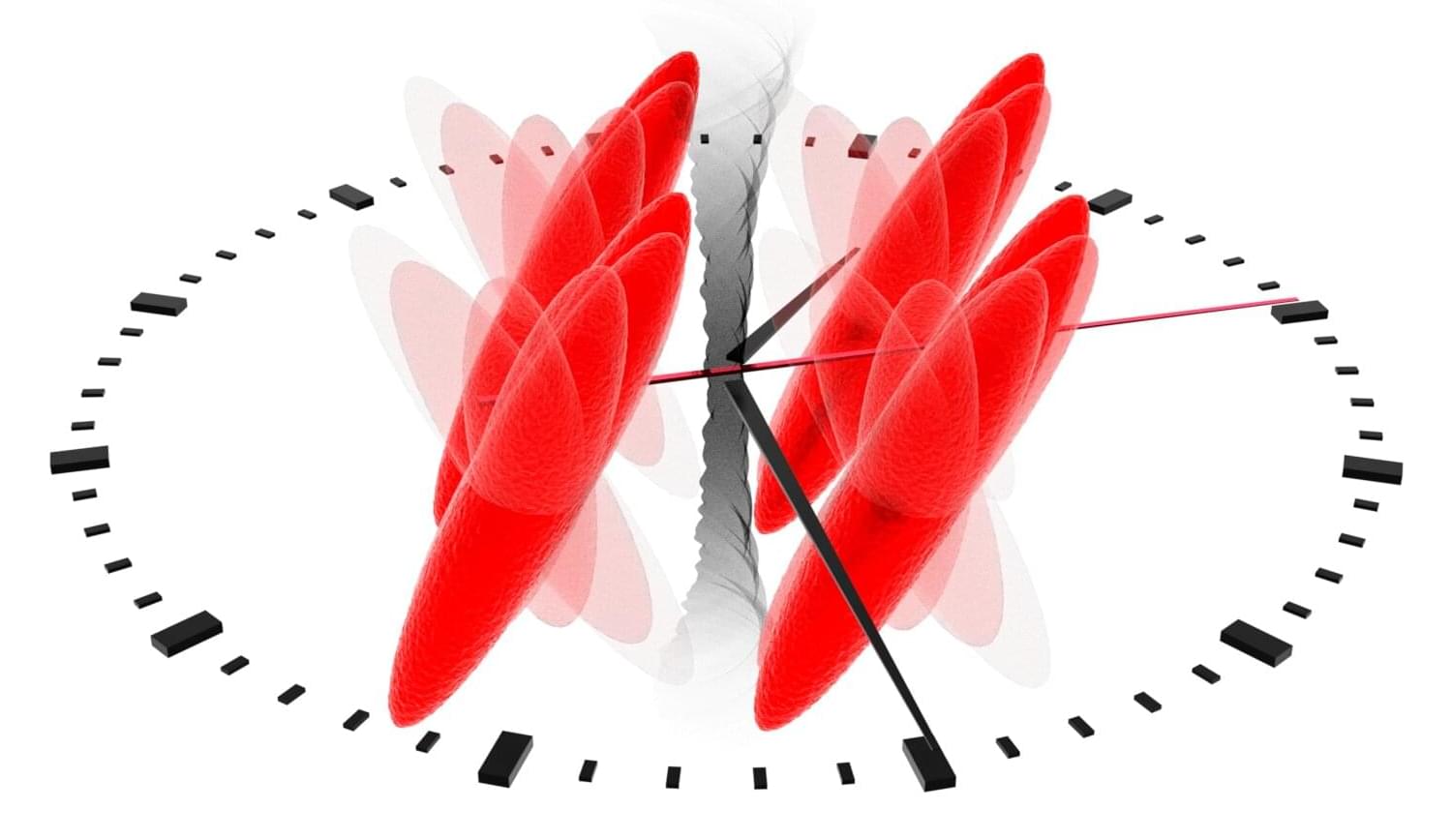

According to a new study by neuroscientists in The Picower Institute for Learning and Memory at MIT, the ability to quickly spot the anomaly could depend on a theta-frequency brain wave (3–6 Hz) that scans through a region of the cortex that maps your field of view.

The findings in animals, published in Neuron, help to explain how the brain implements visual working memory and why performance is both limited and variable.