Viral infections are amongst the most common diseases affecting people worldwide. New viruses emerge all the time and presently we have limited number of vac…

Exercise is extremely important, especially if we don’t move around much at work. There are plenty of apps and watches that can tell us when to move and be active. Primary care physicians emphasize exercise as a preventive measure against symptoms of aging. We are told that consistent exercise with a healthy diet is crucial for a high quality of life. As a result, we are all trying new diets and exercise routines to improve our health. Interestingly, there are specific regimens for individuals at different stages of life. Even cancer patients are encouraged to maintain as much of an active lifestyle as possible. However, how much does exercise really affect our health in cancer? Couldn’t we just each healthier?

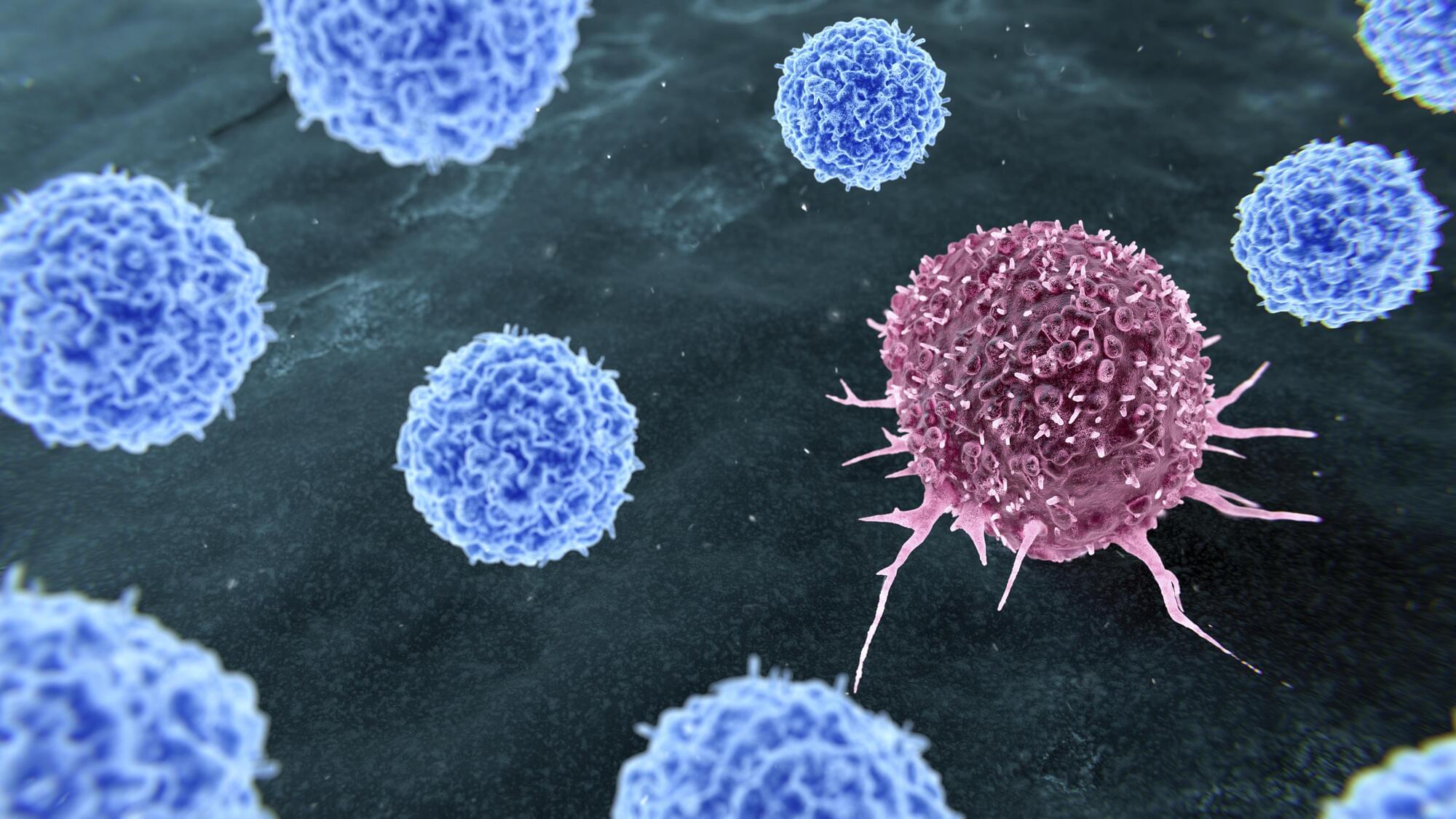

A research group at the University of Pittsburgh discovered that exercise directly alters gut microbes which improve anticancer immunity. The paper published in Cell, by Dr. Marlies Meisel, Catherine Phelps, and others, demonstrated the mechanism that occurs in the gut after exercising. Meisel is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Immunology at the University at Pittsburgh. Catherine Phelps is a talented graduate student in the Meisel Lab and first author on the publication. Meisel’s research focuses on the mechanisms of the microbiota and its effect on systemic immunity. Specifically, she works to understand the role of the microbiome in the context of cancer and autoimmune disorders to improve therapeutic outcomes.

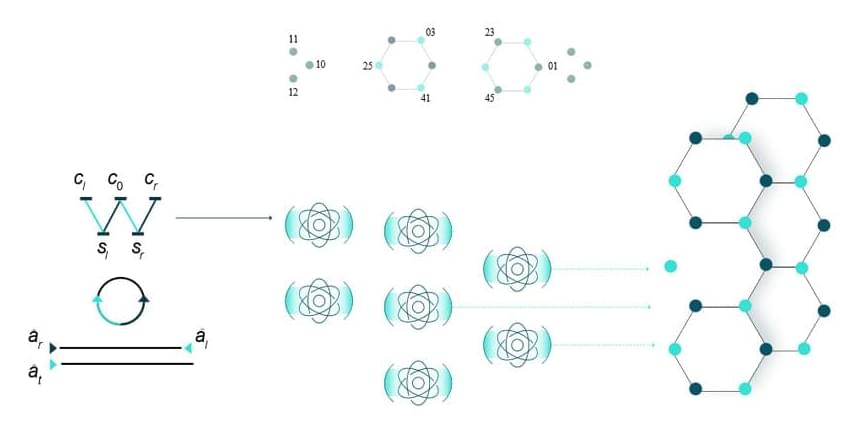

Previous work in the field demonstrated that exercise improves cancer therapy. Additionally, it was known that exercise changes the gut microbiome, which includes various bacteria that is helpful to the body. However, there was a gap missing between these two findings. Meisel and her team set out to understand how these two ideas were linked. Specifically, they wanted to know how exercise changes the gut microbiome to improve cancer immunotherapy. Catherine and other researchers in the Meisel Lab had mice exercise for four weeks in one group and had another group that did not exercise. When they implanted tumors, they found that the mice that exercised had smaller tumors compared to the no-exercise group. However, when researchers conducted the same experiment with mice that were germ-free or treated with antibiotics to eliminate the gut microbiome, they lost the change in tumor growth.

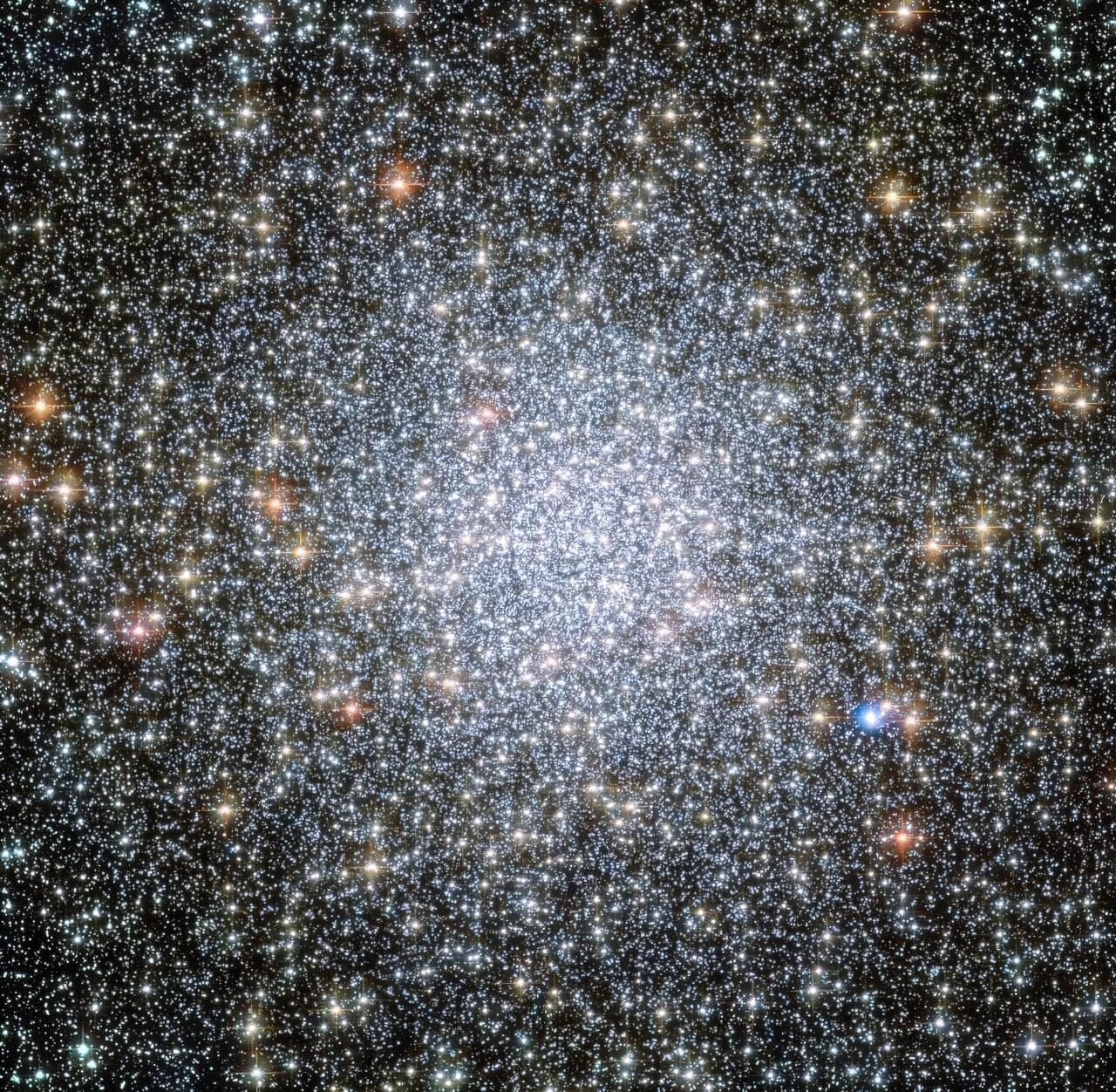

Astronomers have studied the globular cluster 47 Tucanae extensively, but still have many questions. It may have an intermediate mass black hole in its center like Omega Centauri is expected to have. There are reasons to believe it may be the remnant of a dwarf galaxy that was gobbled up by the Milky Way, like other GCs. Also like other GCs, its center is extraordinarily dense with stars, and astronomers aren’t certain how far the cluster spreads.

Individual stars in 47 Tuc are difficult to observe because they’re so tightly packed in the center and because they’re difficult to differentiate from field stars on its outer edges. Can the Vera Rubin Observatory help?

Early data from the Vera Rubin and its Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST) were designed to test and refine the telescope’s system. But it’s still good quality data, and researchers are using it to not only understand how the Vera Rubin Observatory (VRO) performs, but also for concrete science results.

Van Leeuwen also cited the example of a group of chimpanzees at a zoo in the Netherlands in which one female started walking as if she were carrying a baby even though she wasn’t.

Soon, all of the females had adopted this walking style, he said. In addition, when two new females were brought into the group, the one that adopted the style swiftly was integrated quickly, whereas the one that refused to walk in the group style took longer to be accepted.

For Van Leeuwen, these behaviors are about fitting in and smoothing social relationships, just as with humans.