When 3D printing is combined with machine learning, magic happens at the nano scale.

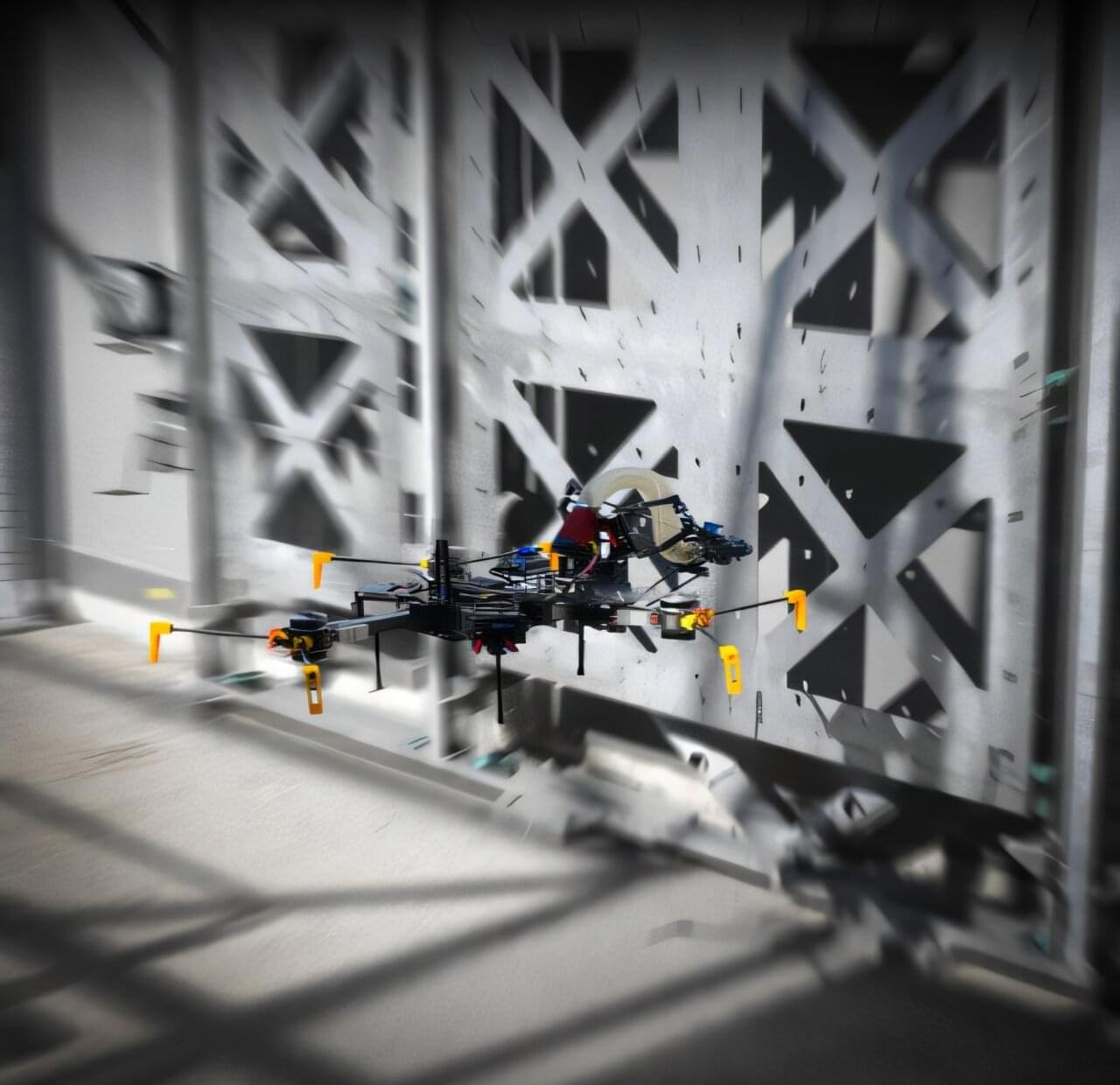

New research led by Imperial College London and co-authored by the University of Bristol, has revealed that aerial robotics could provide wide-ranging benefits to the safety, sustainability and scale of construction.

The research examines the emerging field of using drones for mid-air material deposition in the construction industry —a process known as Aerial Additive Manufacturing (Aerial AM).

This technology addresses pressing global housing and infrastructure challenges using aerial robots equipped with advanced manipulators that can overcome the limitations of traditional construction methods and ground-based robotic systems.

Over 100 red sprites were captured above the Himalayas in 2022. A study linked them to strong lightning strikes in a large thunderstorm system and introduced a new timing method for analysis. Have you ever heard of or seen red lightning? These are not animated characters, but real atmospheric ph

Non-reciprocal interactions between particles enable the regulation of dynamic states. Most systems, whether companies, societies, or entire nations, tend to function most effectively when each member performs their designated role. This efficiency is often supported by spatial organization, whic

Discover QNodeOS, the world’s first operating system for quantum computers, which aims to connect different quantum machines and drive the future of quantum computing.

Researchers have developed a noninvasive brain-spine interface that detects movement intentions and cues spinal cord stimulation to aid rehabilitation.

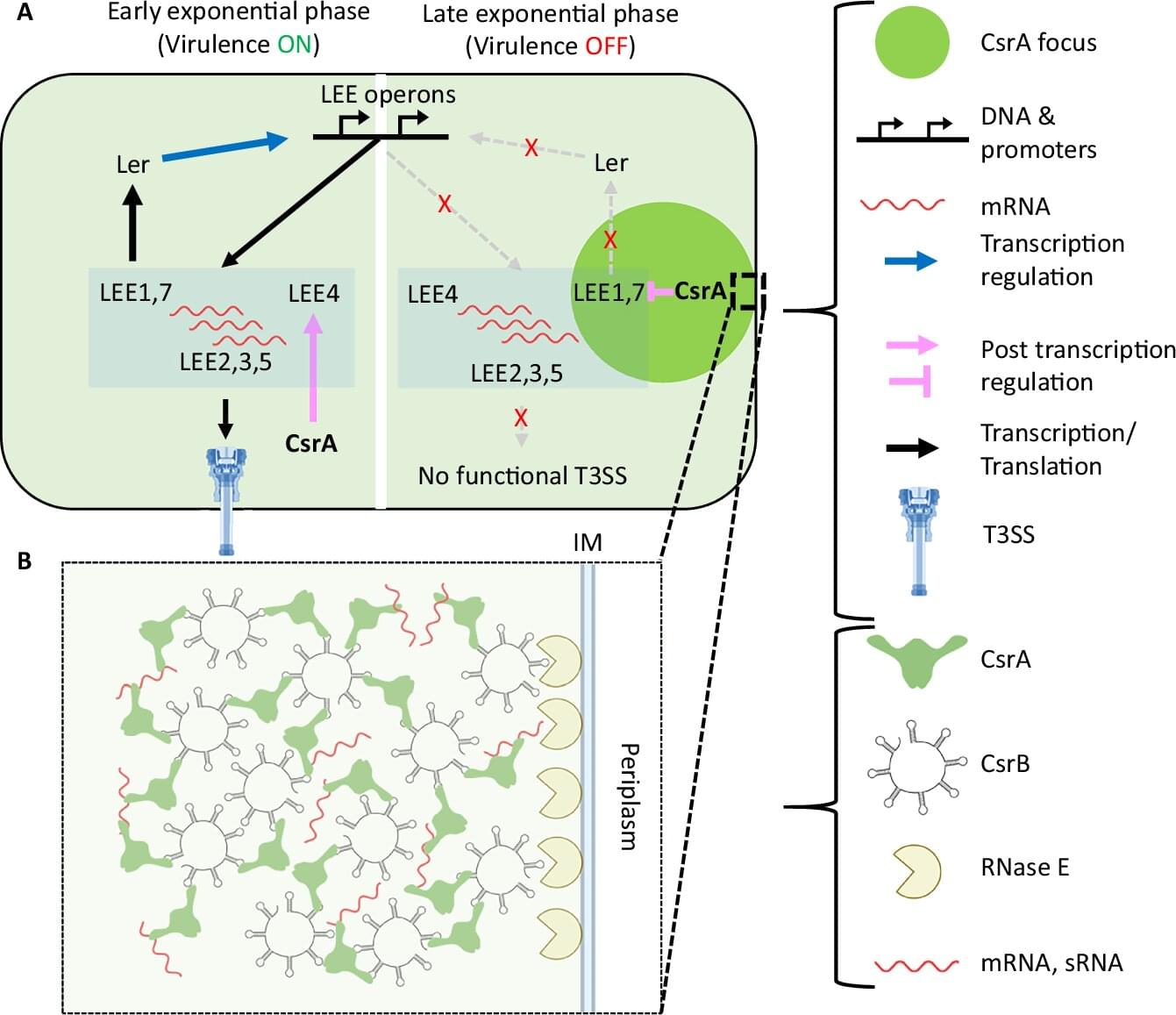

Scientists at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem have uncovered a surprising way in which harmful bacteria prepare to attack their hosts. The discovery, led by Ph.D. students Lior Aroeti, Netanel Elbaz under the guidance of Prof. Ilan Rosenshine from the Faculty of Medicine could one day help researchers find new ways to fight infectious diseases.

At the heart of this study, now published in Nature Communications, is a protein called CsrA, which acts like a switchboard operator inside bacterial cells. It helps bacteria decide which of their genes to turn on or off—especially the genes that make them dangerous to humans.

Researchers have long known that CsrA plays a central role in bacterial virulence—the ability of bacteria to cause disease. But the new study shows that CsrA doesn’t work alone. Instead, it gathers in a special, droplet-like structure inside the cell. This structure has no membrane, making it a “membraneless compartment,” which scientists now believe is crucial in regulating how bacteria behave.

The weird paradox of Schrödinger’s cat has found a lasting popularity. What does it mean for the future of quantum physics?

Michael Elowitz on the early years of synthetic biology and the programmability of living cells.

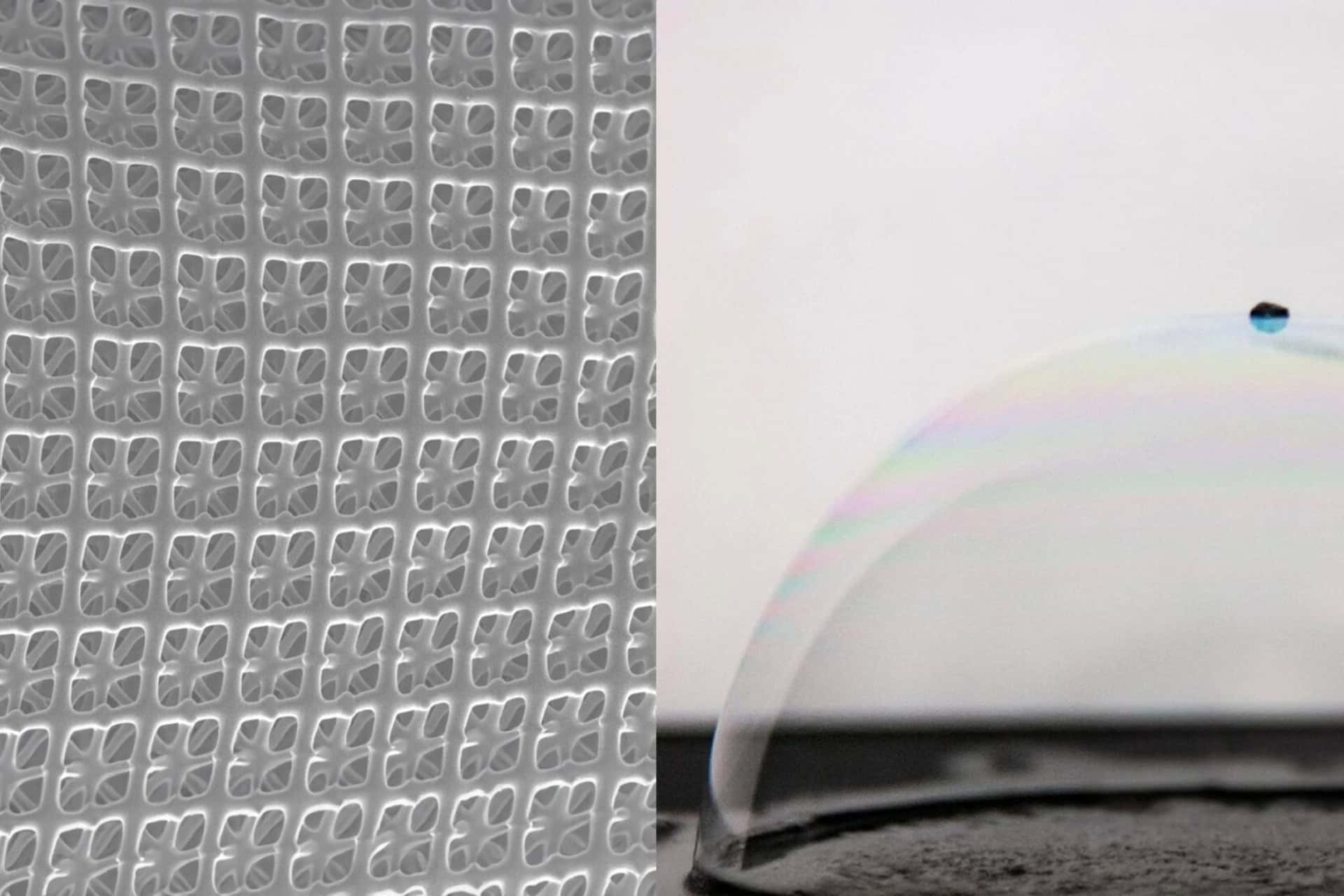

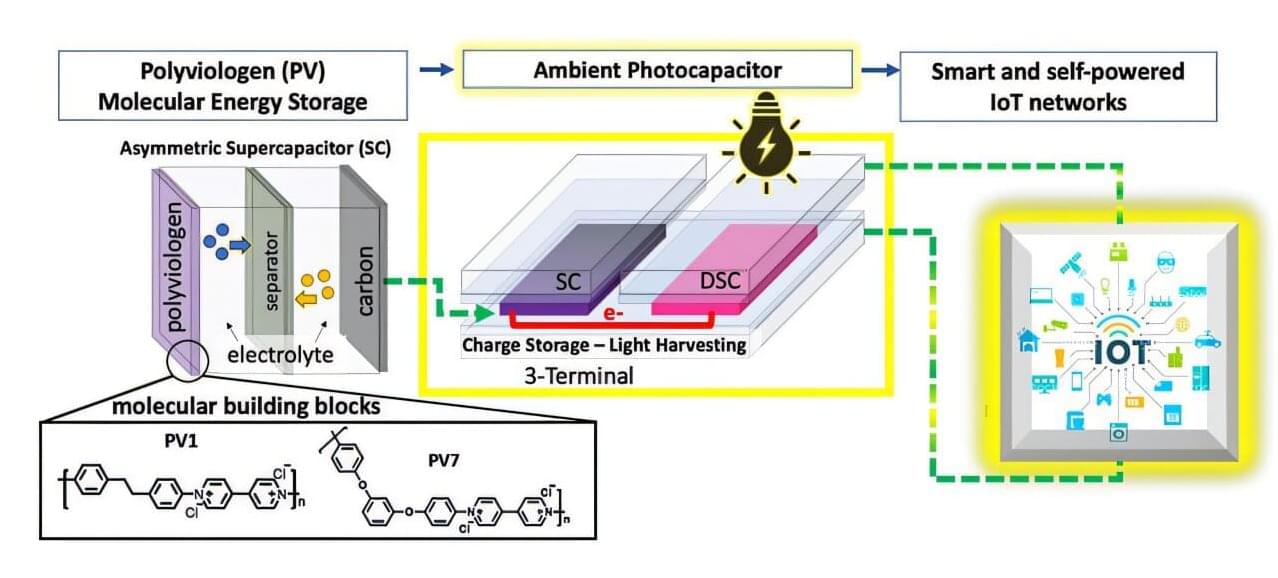

A landmark international collaboration led by Newcastle University has developed the world’s most efficient integrated light-harvesting and storage system for powering autonomous Artificial Intelligence (AI) at the edge of the Internet of Things (IoT).