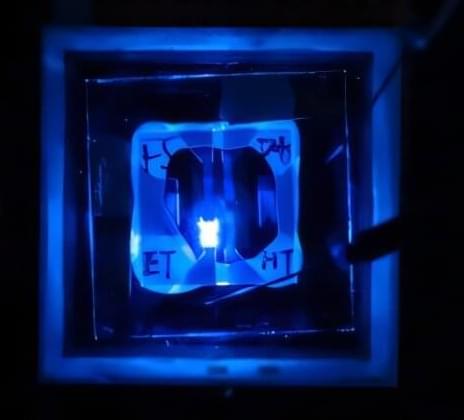

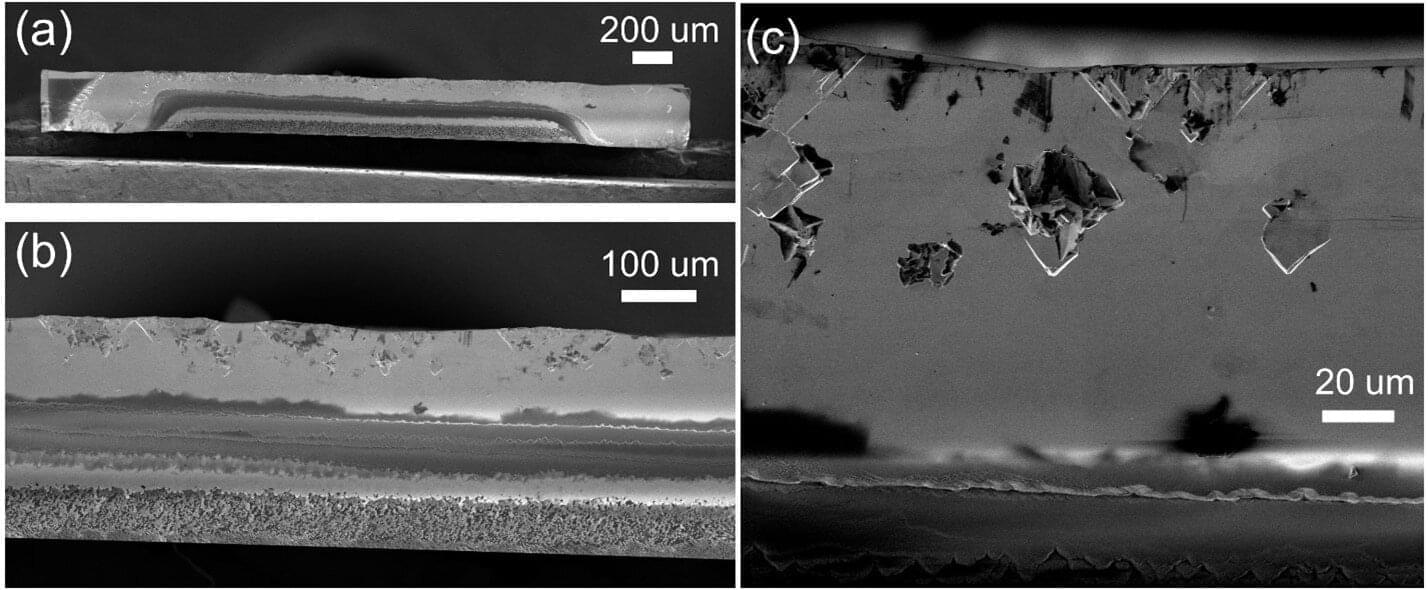

Blue phosphorescent OLEDs can now last as long as the green phosphorescent OLEDs already in devices, University of Michigan researchers have demonstrated, paving the way for further improving the energy efficiency of OLED screens.

“This moves the blues into the domain of green lifetimes,” said Stephen Forrest, the Peter A. Franken Distinguished University Professor of Electrical Engineering and corresponding author of the study in Nature Photonics.

“I can’t say the problem is completely solved—of course it’s not solved until it enters your display—but I think we’ve shown the path to a real solution that has been evading the community for two decades.”