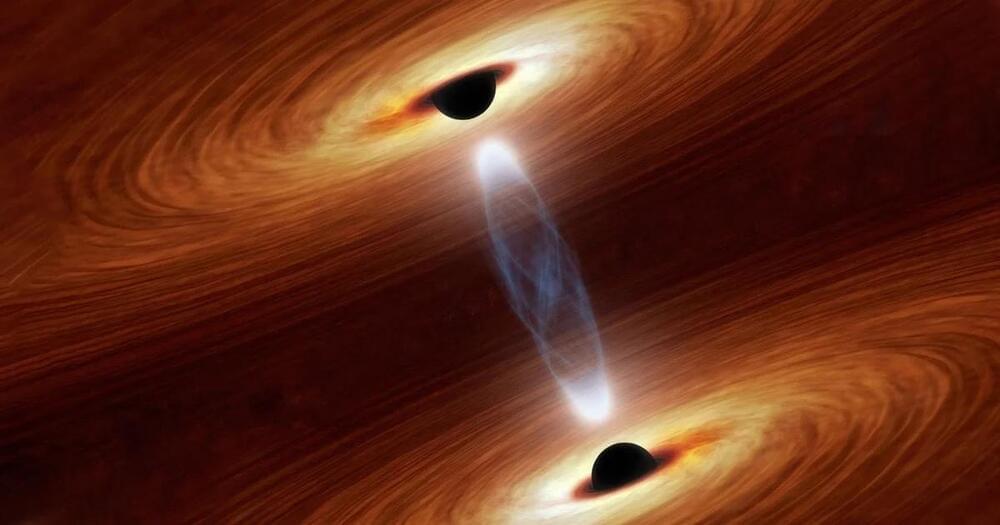

Two supermassive black holes will collide in 10,000 years, warping space and time.

A Cosmic Collision in the Making

In a galaxy 9 billion light-years away, two enormous black holes are locked in a cosmic dance that will eventually end in a massive collision. These supermassive black holes, each hundreds of millions of times the mass of our sun, are currently orbiting one another. In about 10,000 years, they will merge in a violent event, unleashing enough force to distort space and time by creating gravitational waves—ripples in the universe’s fabric.