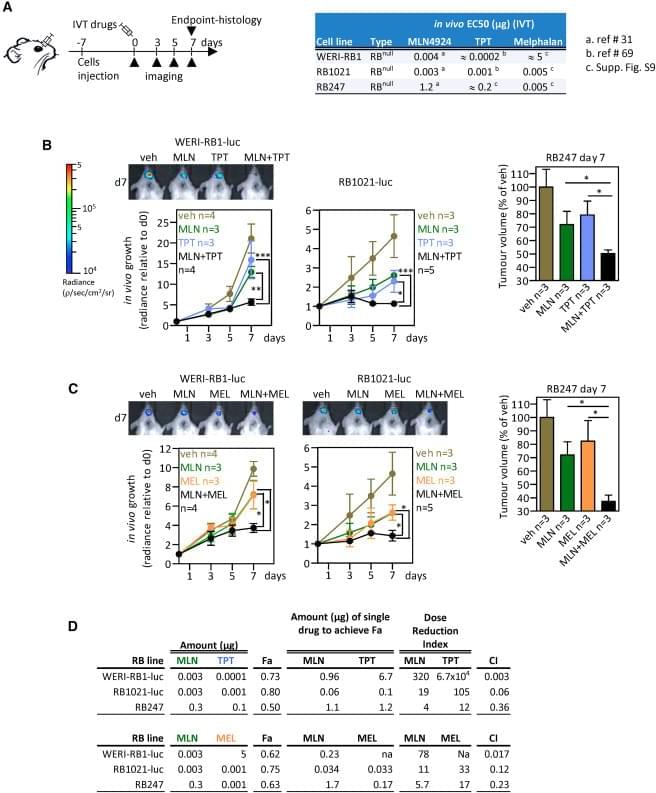

(Cell Reports 42, 112925; August 29, 2023)

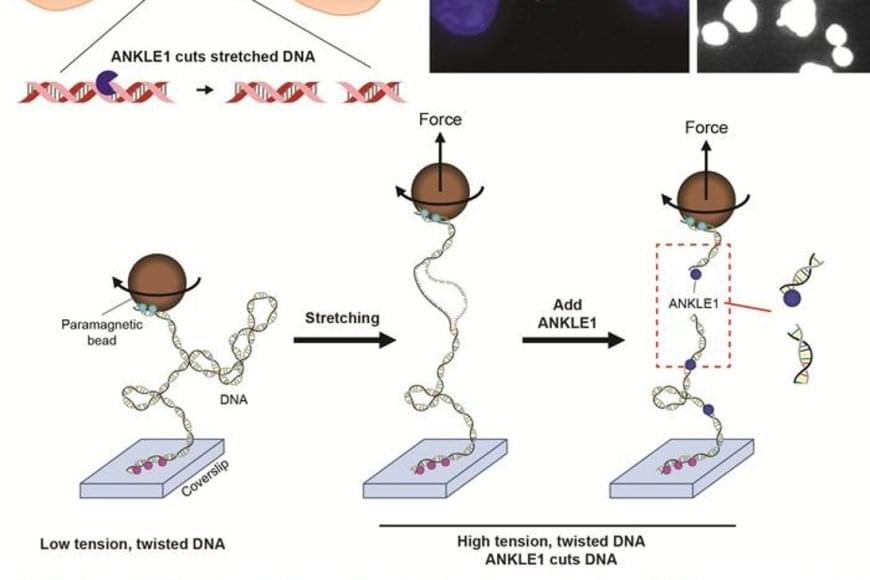

The authors were made aware of an image duplication in their published paper. The representative photo in Figure 5B is the same as the image in Fig. 4g of Aubry et al., 2020, Oncogene 39, p. 5338–5357. The assays involved treating xenografts of the RB1021-luc retinoblastoma line, using either MLN4924 (MLN) and topotecan (TPT; Cell Reports) or the RAD51 inhibitor B02 and TPT (Oncogene). These assays were run and analyzed concurrently in 2018. For the Xenogen measurements of tumor growth, we first quantified the signal and recorded the values in tables. After all the mice were assessed, appropriate mice were placed together for representative images. Thus, the quantification, which was performed correctly, and acquisition/storage of the representative image, which was not, were performed separately. Our review of image files revealed that the representative image of the B02 + TPT series of mice was accidentally duplicated using the file name for the MLN + TPT series of mice.