Humanoid robots are on the cusp of mass adoption. And Elon Musk’s Tesla bots aren’t the only game in town.

There are ways of cooling the planet, and then there are cool ways of cooling the planet. Spending decades grinding up something approaching a quadrillion dollars worth of diamonds into dust, and then dispersing the powdered gemstones into our atmosphere? That falls into the latter. Contrary to what you might…

Sweden’s Alight and Finland’s 3Flash have entered into a joint development agreement to build a 120 MW solar park in Loviisa, a town in southeastern Finland.

Construction is expected to begin early next year, with commissioning currently scheduled for 2027. Once completed, it is expected to generate 155 GWh, equivalent to the annual electricity needs of 31,000 households.

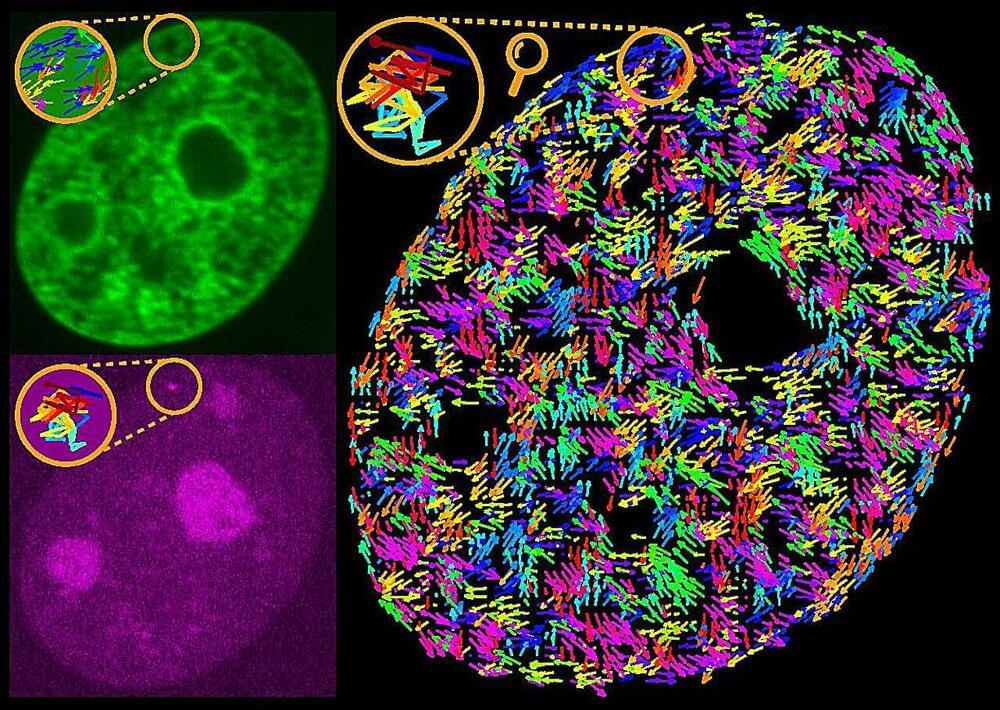

A team of scientists has discovered surprising connections among gene activity, genome packing, and genome-wide motions, revealing aspects of the genome’s organization that directly affect gene regulation and expression.

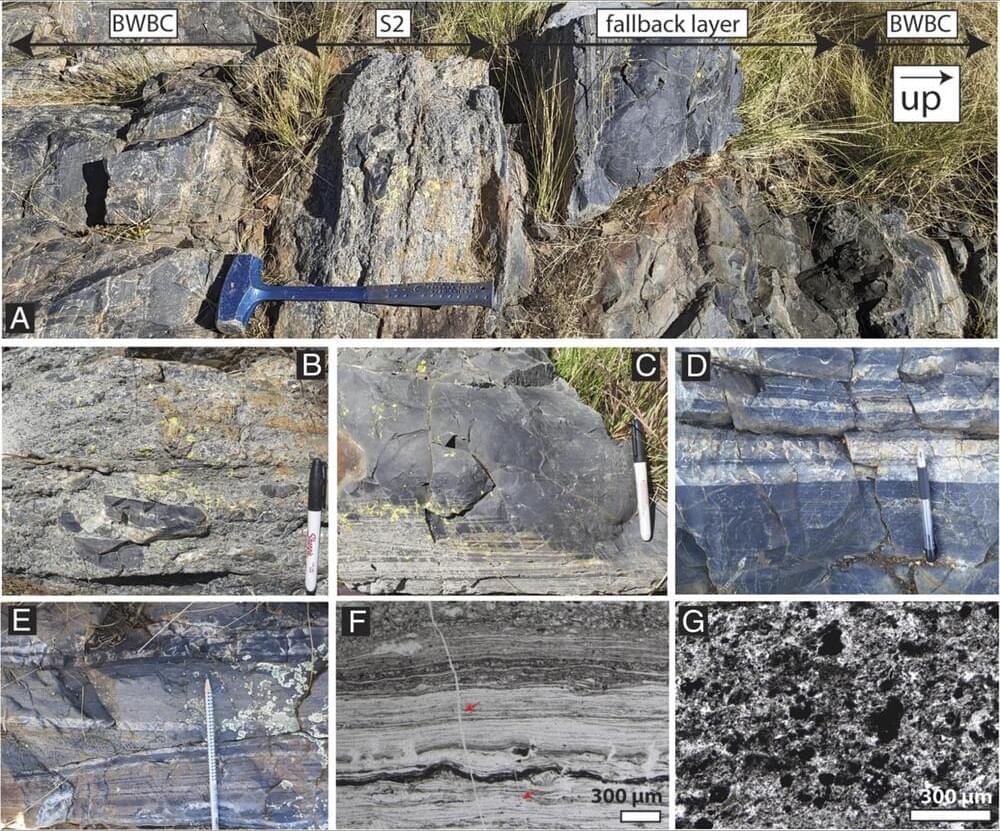

Large meteorite impacts must have strongly affected the habitability of the early Earth. Rocks of the Archean Eon record at least 16 major impact events, involving bolides larger than 10 km in diameter. These impacts probably had severe, albeit temporary, consequences for surface environments. However, their effect on early life is not well understood. Here, we analyze the sedimentology, petrography, and carbon isotope geochemistry of sedimentary rocks across the S2 impact event (37 to 58 km carbonaceous chondrite) forming part of the 3.26 Ga Fig Tree Group, South Africa, to evaluate its environmental effects and biological consequences.

New research has found that a mineral found in Brazil nuts could be the key to stopping the spread of triple negative breast cancer.

Triple negative breast cancer can be hard to treat but is often manageable through therapy and surgery, unless it spreads to other parts of the body when it can become inoperable.

The study, funded by Cancer Research UK, suggests that limiting the antioxidant effects of selenium, a popular ingredient of multivitamin supplements found in everyday foods such as nuts, meat, mushrooms and cereals, could be the secret to controlling this form of the disease.

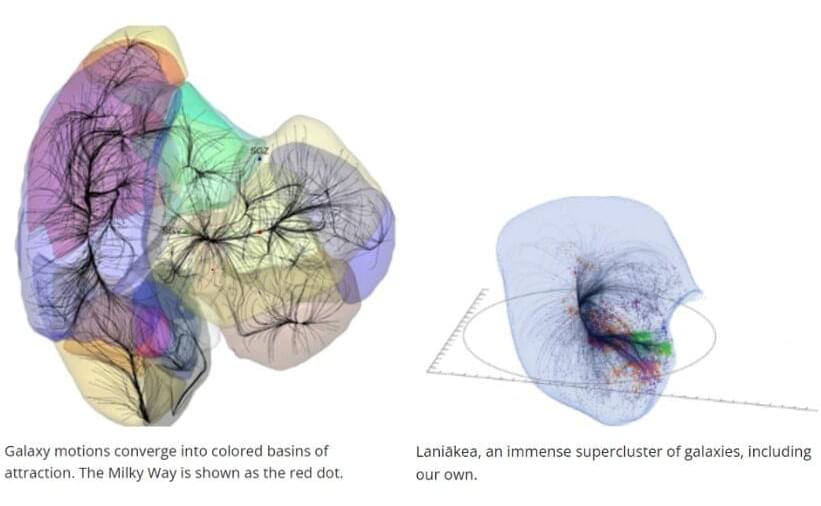

The Cosmicflows team has been studying the movements of 56,000 galaxies, revealing a potential shift in the scale of our galactic basin of attraction. A team of international researchers guided by astronomers at University of Hawai’i Institute for Astronomy is challenging our understanding of the universe with groundbreaking findings that suggest our cosmic neighborhood may be far larger than previously thought.

A decade ago, the team concluded that our galaxy, the Milky Way, resides within a massive basin of attraction called Laniākea, stretching 500 million light-years across.

However, new data suggests that this understanding may only scratch the surface.

Tohoku University’s Dr. Le Bin Ho has explored how quantum squeezing can improve measurement precision in complex quantum systems, with potential applications in quantum sensing, imaging, and radar technologies. These findings may lead to advancements in areas like GPS accuracy and early disease detection through more sensitive biosensors.

Quantum squeezing is a concept in quantum physics where the uncertainty in one aspect of a system is reduced while the uncertainty in another related aspect is increased. Imagine squeezing a round balloon filled with air. In its normal state, the balloon is perfectly spherical. When you squeeze one side, it gets flattened and stretched out in the other direction. This represents what is happening in a squeezed quantum state: you are reducing the uncertainty (or noise) in one quantity, like position, but in doing so, you increase the uncertainty in another quantity, like momentum. However, the total uncertainty remains the same, since you are just redistributing it between the two. Even though the overall uncertainty remains the same, this ‘squeezing’ allows you to measure one of those variables with much greater precision than before.

This technique has already been used to improve the accuracy of measurements in situations where only one variable needs to be precisely measured, such as in improving the precision of atomic clocks. However, using squeezing in cases where multiple factors need to be measured simultaneously, such as an object’s position and momentum, is much more challenging.