Google wants you to browse the internet with your contact lenses.

Posted in internet

Here is the real challenge to ask the average parent or grandparent on the street: are you willing to allow your 5 year old child or grandchild to have a brain tumor removed by an autonomous robot without any trained & experienced surgeon or nurse supervision?

An unmanned robot has been used to stitch together a pig’s bowel, moving science a step closer to automated surgery, say experts.

Unlike existing machines, the Star robot is self-controlled — it doesn’t need to be guided by a surgeon’s hands.

In tests on pigs, it at least matched trained doctors at mending cut bowel, Science Translational Medicine reports.

My verdict will continue to be out on this version. Unless we truly see a QC environment where the full testing of Cryptography, infrastructure, etc. is tested then at best we’re only looking at a pseudo version of QC. Real QC is reached when the infrastructure fully can take advantage of QC not just one server or one platform means we have arrived on QC. So, I caution folks from over-hyping things because the backlash will be extremely costly and detrimental to many.

IBM has taken its quantum computing technology to the cloud to enable users to run experiments on an IBM quantum processor.

Big Blue has come a long way, baby. IBM announced it is making quantum computing available on the IBM Cloud to accelerate innovation in the field and find new applications for the technology.

(Source: Jimmy Pike & Christopher Wilder ©Moor Insights & Strategy)

Microsoft and Facebook recently announced how they plan to drive leadership in the digital transformation and cloud market: bots. As more companies—especially application vendors—begin to drive solutions that incorporate machine learning, natural language, artificial intelligence, and structured and unstructured data, bots will increase in relevance and value. Google’s Cloud Platform (GCP) and Microsoft see considerable opportunities to enable vendors and developers to build solutions that can see, hear and learn as well as applications that can recognize and learn from a user’s intent, emotions, face, language and voice.

Bots are not new, but they have evolved over time through the evolution of artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning, ubiquitous connectivity and increases in data processing speeds. In the mid-1990s, the first commercial bots were developed. For example, I was on the ground floor for the first commercial chat providers called ichat. As with many disruptive media-based technologies, as was the case with ichat, early adopters tend to be the darker side of the entertainment industry. These companies saw a way to get website visitors to stay online longer by having someone to interact with their guests at 3AM. Out of this necessity, chatbots were developed. Thankfully, the technology has evolved and now bots are mainstream and are being used to helping people perform simple tasks and interact with service providers.

I find this amusing because much of the top US AI talent has worked for many decades in the National Labs and not always in academia. National labs often is a mix of top scientists, engineers as well as academia; not academia only. Granted universities do incubations such a GA Tech, VA Tech, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, etc.; however, the bulk of AI and other patented innovations truly have come out of the national labs such as X10, Los Alamos, Argonne, over the years.

The high demand for AI talents at giant corporations This means the academe is directly affected because their smartest AI experts are rapidly transferring to the corporate world and leaving the academe.

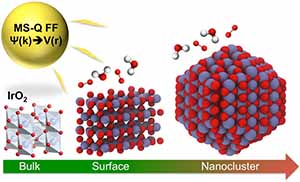

Iridium oxide (IrO2) nanoparticles are useful electrocatalysts for splitting water into oxygen and hydrogen — a clean source of hydrogen for fuel and power. However, its high cost demands that researchers find the most efficient structure for IrO2 nanoparticles for hydrogen production.

A study conducted by a team of researchers at the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE’s) Argonne National Laboratory, published in Journal of Materials Chemistry A, describes a new empirical interatomic potential that models the IrO2 properties important to catalytic activity at scales relevant to technology development. Also known as a force field, the interatomic potential is a set of values describing the relationship between structure and energy in a system based on its configuration in space. The team developed their new force field based on the MS-Q force field.

“Before, it was not possible to optimize the shape and size of a particle, but this tool enables us to do this,” says Maria Chan, assistant scientist at Argonne’s Center for Nanoscale Materials (CNM), a DOE Office of Science User Facility.

Deep Space Industries and the Luxembourg Government announce partnership to commercialize space resources.

Asteroid mining company Deep Space Industries, together with the Luxembourg Government and the Société Nationale de Crédit et d’Investissement (SNCI), the national banking institution in Luxembourg, have signed an agreement formalizing their partnership to explore, use, and commercialize space resources as part of Luxembourg’s spaceresources.lu initiative.

The Luxembourg Government will work with Deep Space Industries to co-fund relevant R&D projects that help further develop the technology needed to mine asteroids and build a supply chain of valuable resources in space.

How could global economic inequality survive the onslaught of synthetic organisms, micromanufacturing devices, additive manufacturing machines, nano-factories?

(http://www.beliefnet.com/columnists/lordre/2016/04/obsessed-…L36KMDo.99)

Narrated by Harry J. Bentham, author of Catalyst: A Techno-Liberation Thesis (2013), using the introduction from that book as a taster of the audio version of the book in production. (http://www.clubof.info/2016/04/liberation-technologies-to-come.html)

Paperback: http://www.amazon.com/Catalyst-Techno-Liberation-Harry-J-Ben…atfound-20

Kindle: http://www.amazon.com/Catalyst-Techno-Liberation-Harry-J-Ben…atfound-20

Audio: coming soon!