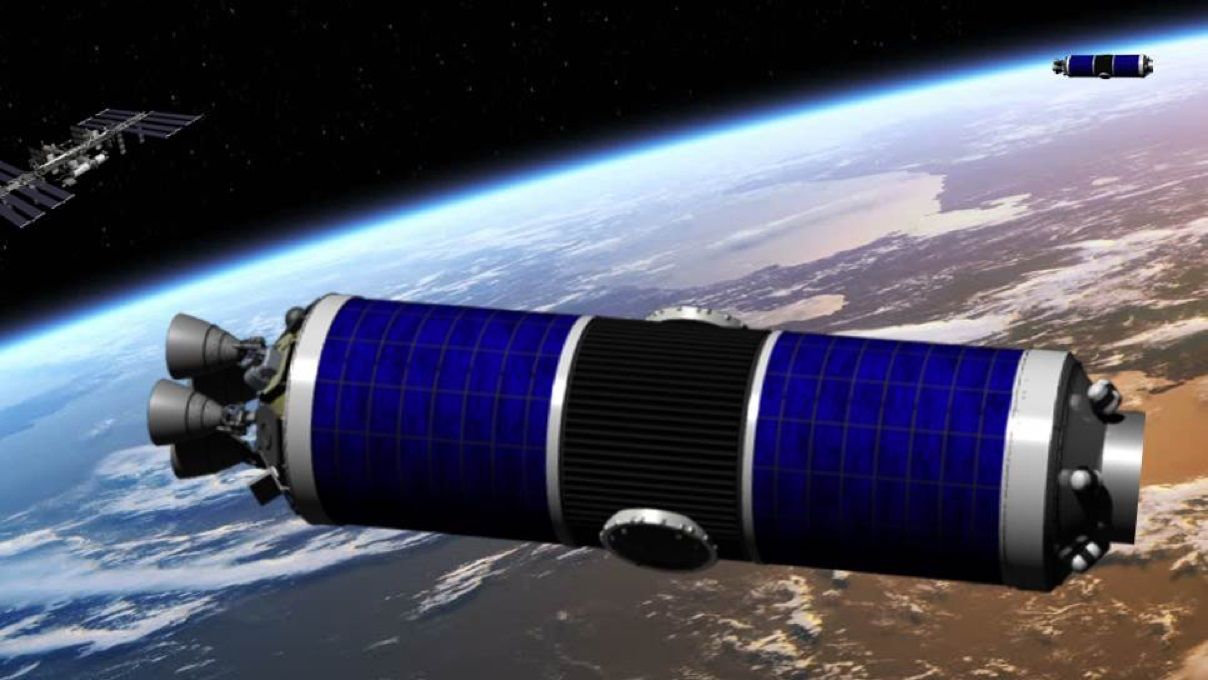

Texas-based NanoRacks is fine-tuning and rebranding its concept for turning upper-stage rocket boosters into orbital outposts, starting with a habitat called Independence-1.

This one’s kinda hard to swallow so take a deep breath, open your minds, and pretend it’s 2100. I CONTACT is essentially a mouse fitted to your eyeball. The lens is inserted like any other normal contact lens except it’s laced with sensors to track eye movement, relaying that position to a receiver connected to your computer. Theoretically that should give you full control over a mouse cursor. I’d imagine holding a blink correlates to mouse clicks.

The idea was originally created for people with disabilities but anyone could use it. Those of us too lazy to use a mouse now have a free hand to do whatever it is people do when they sit at the computer for endless hours. I love the idea but there is a caveat. How is the lens powered? Perhaps in the future, electrical power can be harnessed from the human body, just not in a Matrix creepy-like way.

Designers: eun-gyeong gwon & eun-jae lee.

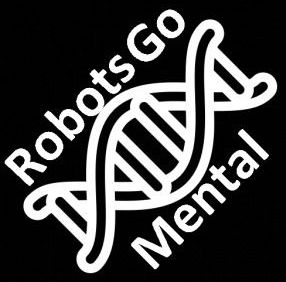

next is an advanced smart transportation system based on swarms of modular self-driving vehicles, refined by italian designers and engineers. the modules can drive autonomously on regular roads, joining themselves and detach even when in motion. when joined, the doors between modules fold, creating a walkable open space among modules. founded by tommaso gecchelin, the concept would greatly outperform conventional transportation when used in conjunction with other modules. the collection of next modules would improve traffic fluidity, commute time, running costs and pollution prevention by optimizing each module occupancy rate.

once linked, passengers would be able to walk between modules

the modules would be individualized

shipping and goods transportation could be adapted

companies would offer specific modules to the system piotr boruslawski I designboom.

Anything that keeps people from getting hit is important.

When the light turns red, a huge laser wall projecting apparitions of crossing pedestrians spans across the crosswalk. The concept is designed to keep crossing pedestrians safe from any overzealous drivers who otherwise might have ran the red light.

NASA has just released an all-new 4K-resolution video showing the surface of the moon in incredible detail. Created using data gathered over the last nine years, the five-minute presentation shows our nearest neighbor like you’ve never seen it before.