Nice.

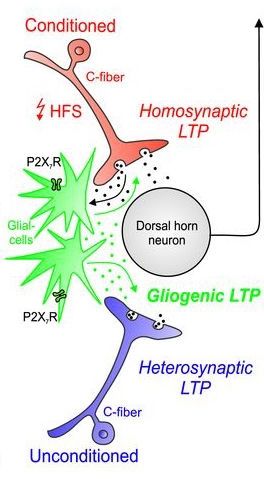

Chronic pain is thought to involve the long-lasting strengthening of synapses, akin to what happens during the formation of new memories. This phenomenon, known as long-term potentiation (LTP), is triggered when neurons on both sides of a synapse are active at the same time. But now, Jürgen Sandkühler, Medical University of Vienna, Austria, and colleagues provide evidence that LTP in nociceptive circuits arises in a different way.

By simultaneously activating two types of glial cells―astrocytes and microglia―the researchers were able to produce LTP at synapses that connect peripheral C-fibers and lamina I neurons in the dorsal horn spinal cord. They also showed that with high-frequency stimulation of C-fibers, glial cells strengthen active and inactive synapses through their release of the NMDA receptor co-agonist D-serine and the cytokine tumor necrosis factor (TNF). Moreover, these molecules traveled to distant synapses, perhaps explaining why pain hypersensitivity can develop in areas surrounding or far away from an injury.

“This paper is going to stimulate a lot of discussion that will lead to important advances for all of us in the pain field,” said Theodore Price, The University of Texas at Dallas, US, who was not involved in the study. “It raises questions for my lab in our day-to-day research that we can address immediately. That’s ultimately the true measure of a really good paper.”