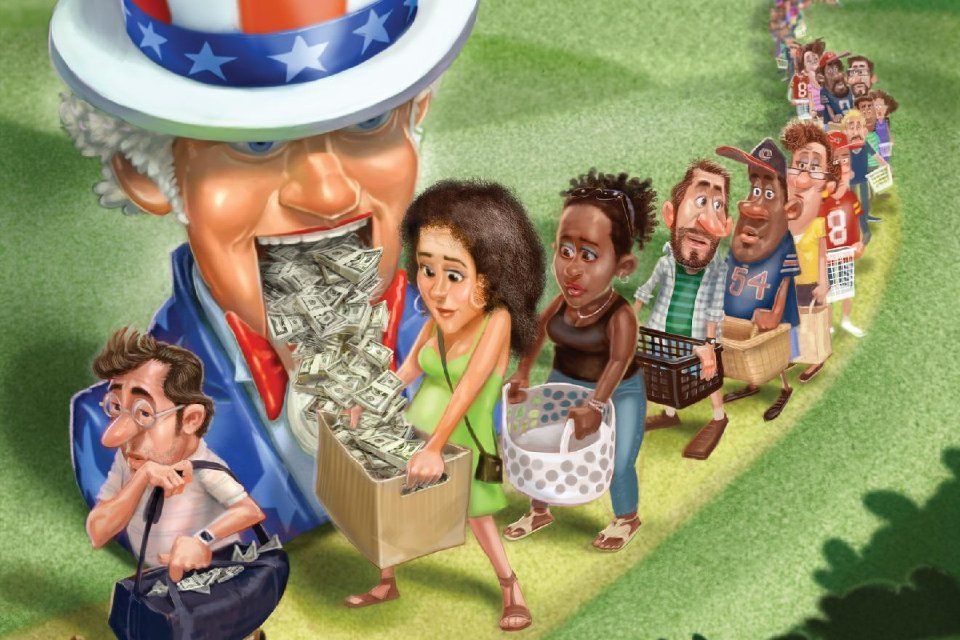

Finally, are we prepared to expand science and technology opportunities for all Americans? The United States has only 5 percent of the world’s population. To stay ahead, we’ll need to use all our assets. That means leveling the barriers for women in science and engineering, and closing the participation gap for underrepresented minorities. It also means expanding tech-driven prosperity beyond the two coasts. Pittsburgh’s success is a proof of principle, but we need to nurture at least a dozen new tech hubs across America, anchored by leading universities.

We need clear answers to six big questions.

To begin, do we care if China surpasses America as the leading spender on research and development? In 2000, China and the United States accounted for roughly 5 and 40 percent, respectively, of global R&D. In 2015, the figures were 21 and 29 percent. At this pace, the lines will cross before 2020. While the average quality of American science remains higher, that gap is closing too.

To be clear, being the global hub of innovation isn’t about bragging rights. It’s about the prosperity that comes with it.