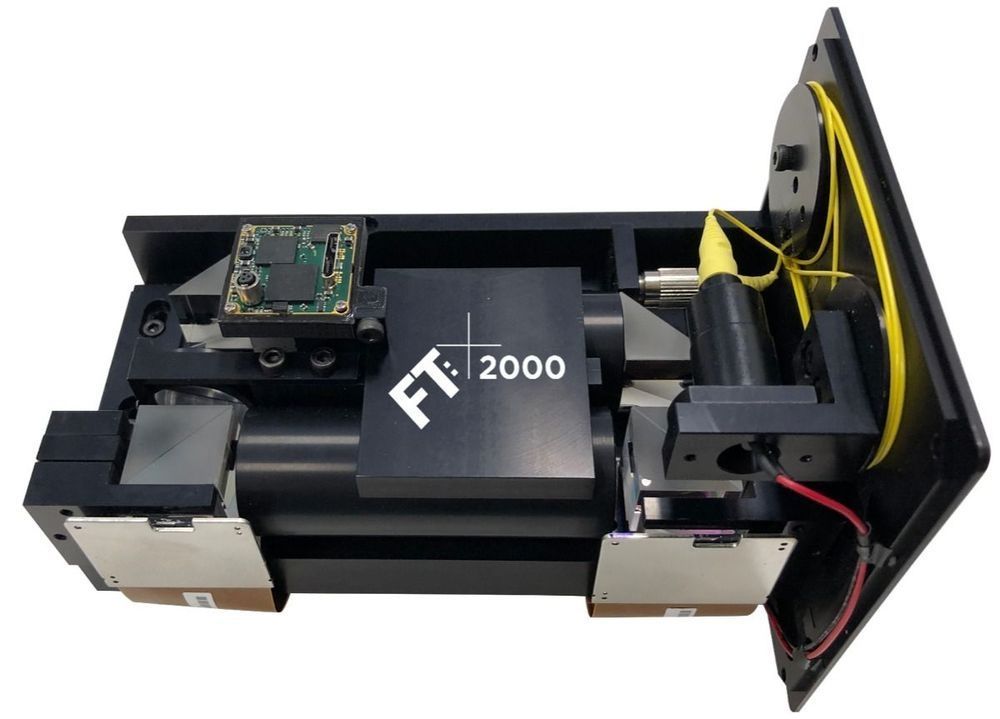

YORKSHIRE, U.K. — 7 MARCH, 2019 — Optalysys Ltd. (@ Optalysys), a disruptive technology company developing light-speed optical AI systems announced today that the world’s first optical co-processor system, the FT: X 2000, is now available to order.

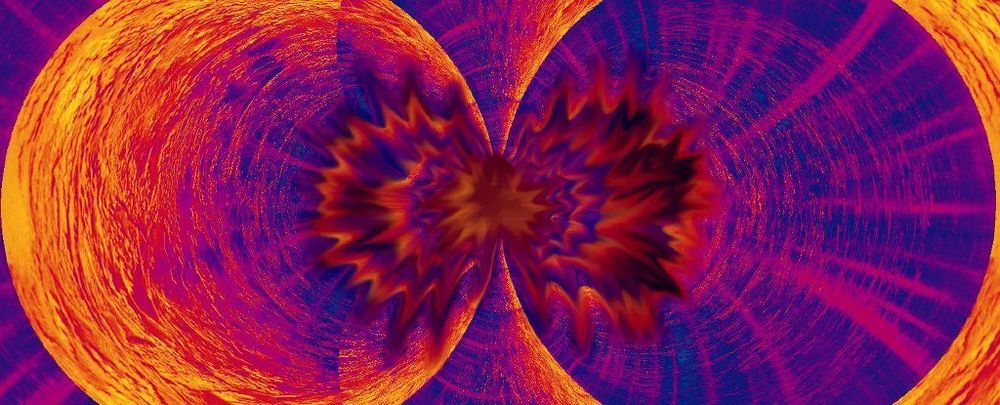

Optical processing comes at a pivotal time of change in computing. Demand for AI is exploding just as silicon-based processing is facing the fundamental problem of Moore’s Law breaking down. Optalysys is addressing this problem with its revolutionary optical processing technology — enabling new levels of AI performance for high resolution image and video-based applications.