Researchers from the Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology teamed up with colleagues from the U.S. and Switzerland and returned the state of a quantum computer a fraction of a second into the past. They also calculated the probability that an electron in empty interstellar space will spontaneously travel back into its recent past. The study is published in Scientific Reports.

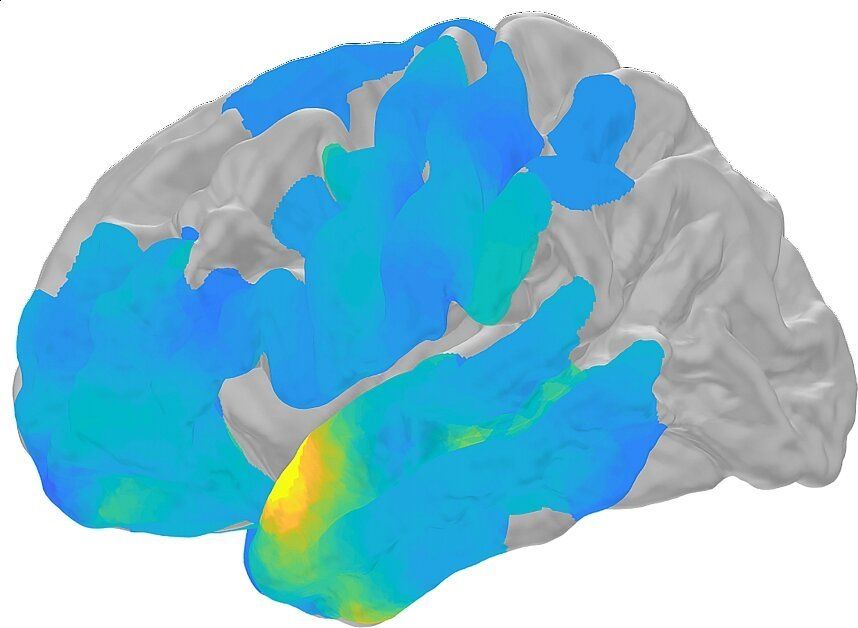

“This is one in a series of papers on the possibility of violating the second law of thermodynamics. That law is closely related to the notion of the arrow of time that posits the one-way direction of time from the past to the future,” said the study’s lead author Gordey Lesovik, who heads the Laboratory of the Physics of Quantum Information Technology at MIPT.

“We began by describing a so-called local perpetual motion machine of the second kind. Then, in December, we published a paper that discusses the violation of the second law via a device called a Maxwell’s demon,” Lesovik said. “The most recent paper approaches the same problem from a third angle: We have artificially created a state that evolves in a direction opposite to that of the thermodynamic arrow of time.”