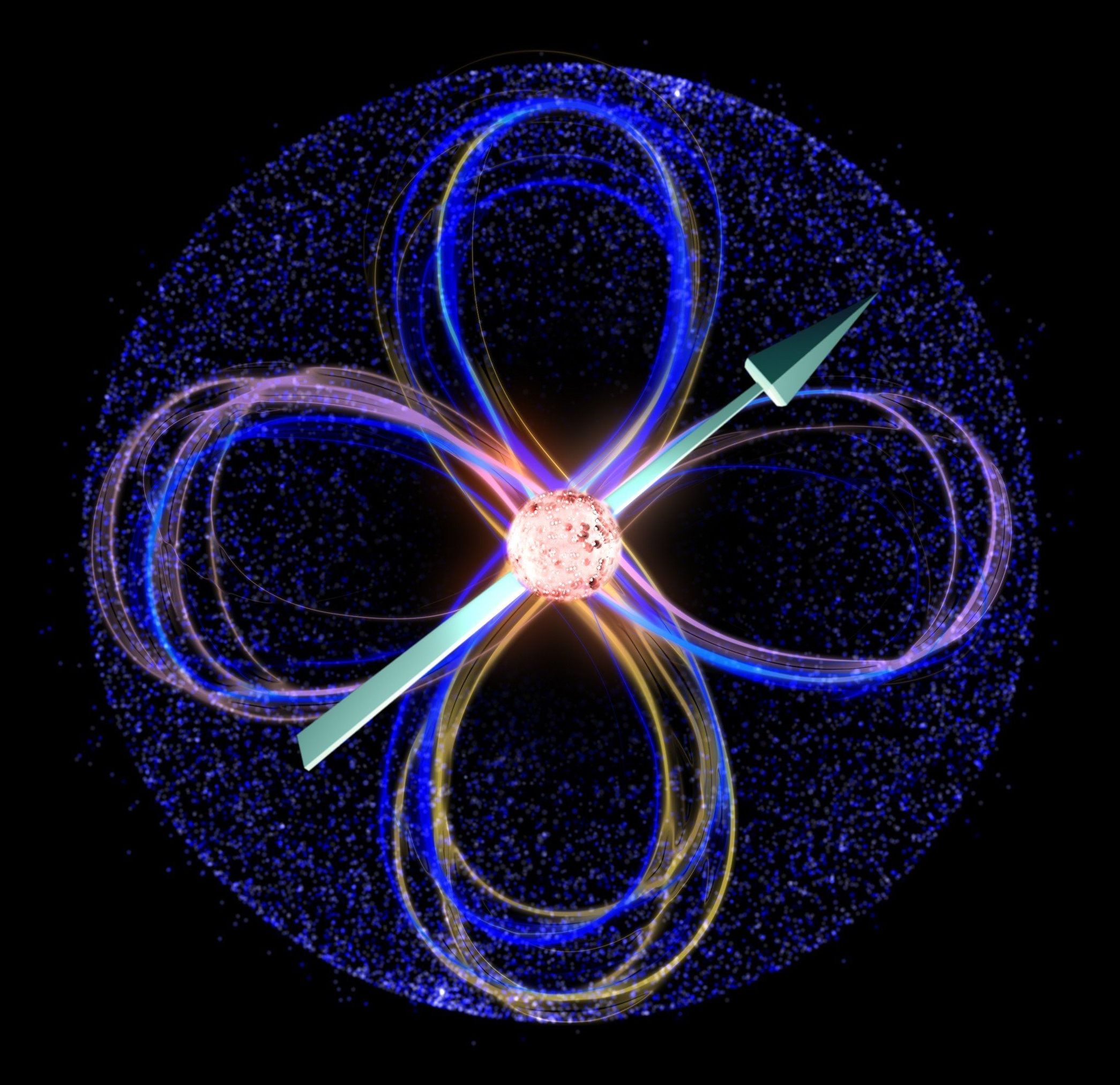

As on Earth, so in space. A four-satellite mission that is studying magnetic reconnection—the breaking apart and explosive reconnection of the magnetic field lines in plasma that occurs throughout the universe—has found key aspects of the process in space to be strikingly similar to those found in experiments at the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory (PPPL). The similarities show how the studies complement each other: The laboratory captures important global features of reconnection and the spacecraft documents local key properties as they occur.

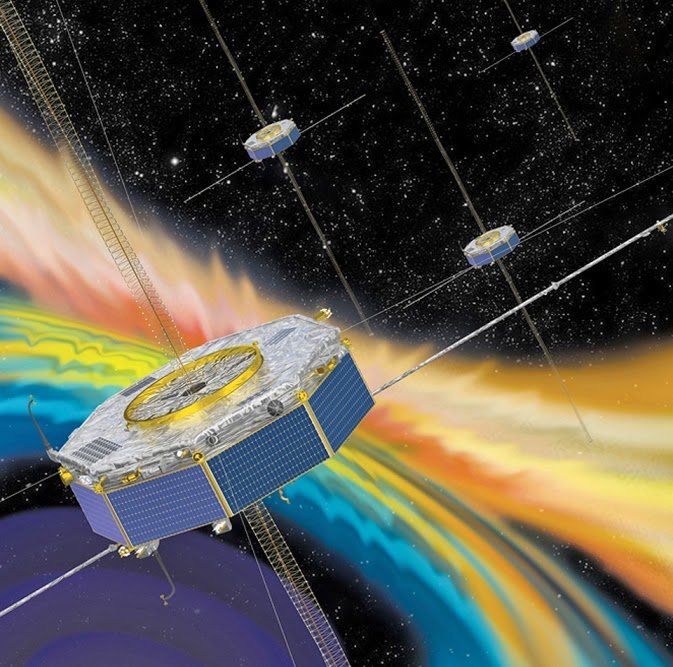

The observations made by the Magnetospheric Multiscale Satellite (MMS) mission, which NASA launched in 2015 to study reconnection in the magnetic field that surrounds the Earth, correspond quite well with past and present laboratory findings of the Magnetic Reconnection Experiment (MRX) at PPPL. Previous MRX research uncovered the process by which rapid reconnection occurs and identified the amount of magnetic energy that is converted to particle energy during the process, which gives rise to northern lights, solar flares and geomagnetic storms that can disrupt cell phone service, black out power grids and damage orbiting satellites.