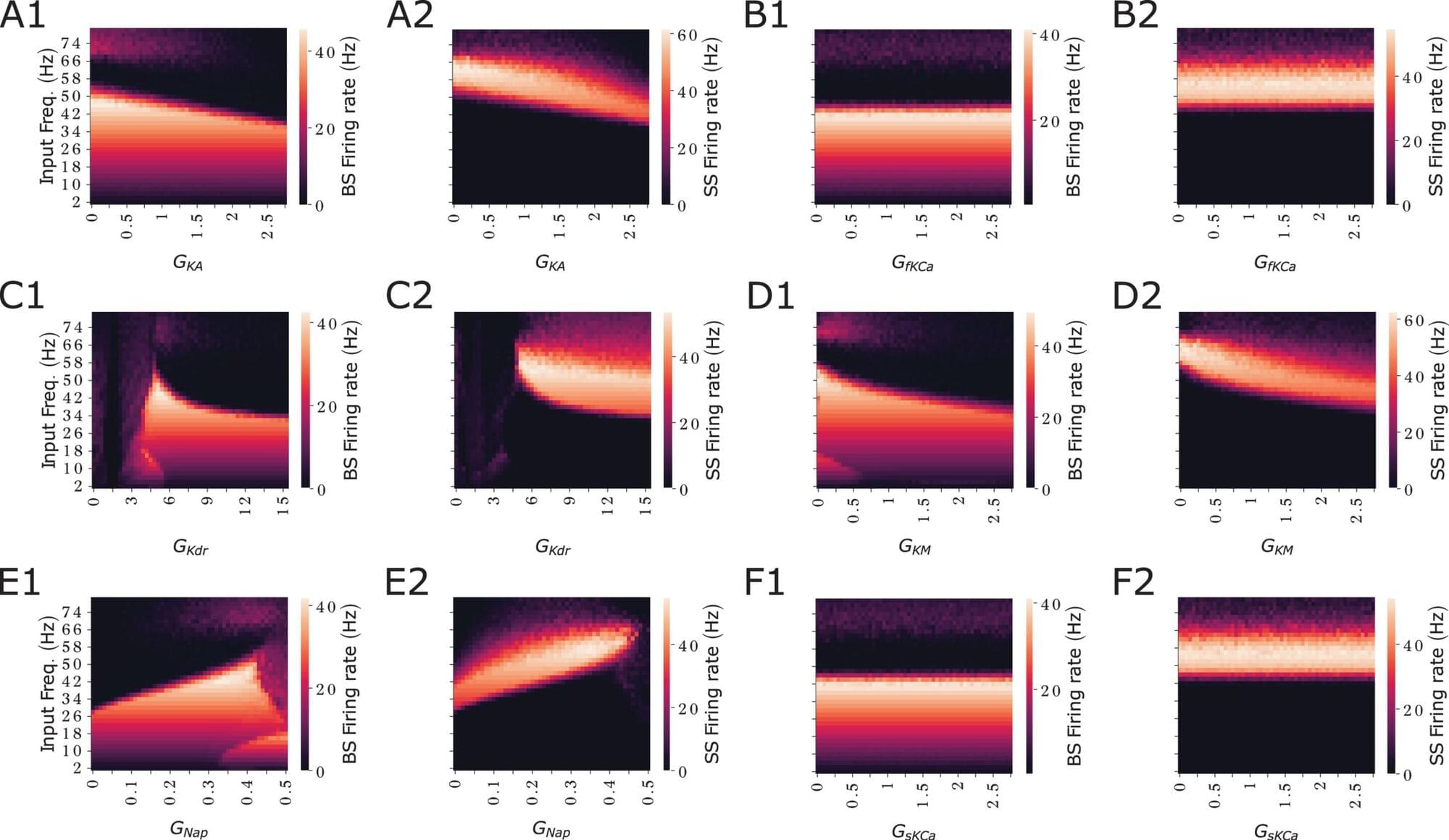

The brain is constantly mapping the external world like a GPS, even when we don’t know about it. This activity comes in the form of tiny electrical signals sent between neurons—specialized cells that communicate with one another to help us think, move, remember and feel. These signals often follow rhythmic patterns known as brain waves, such as slower theta waves and faster gamma waves, which help organize how the brain processes information.

Understanding how individual neurons respond to these rhythms is key to unlocking how the brain functions related to navigation in real time—and how it may be affected in disease.

A new study by Florida Atlantic University and collaborators from Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, Netherlands, and the University of Amsterdam, Netherlands, has uncovered a surprising ability of brain cells in the hippocampus to process and encode and respond to information from multiple brain rhythms at once.