Graphene is known as the world’s thinnest material due to its 2-D structure, in which each sheet is only one carbon atom thick, allowing each atom to engage in a chemical reaction from two sides. Graphene flakes can have a very large proportion of edge atoms, all of which have a particular chemical reactivity. In addition, chemically active voids created by missing atoms are a surface defect of graphene sheets. These structural defects and edges play a vital role in carbon chemistry and physics, as they alter the chemical reactivity of graphene. In fact, chemical reactions have repeatedly been shown to be favoured at these defect sites.

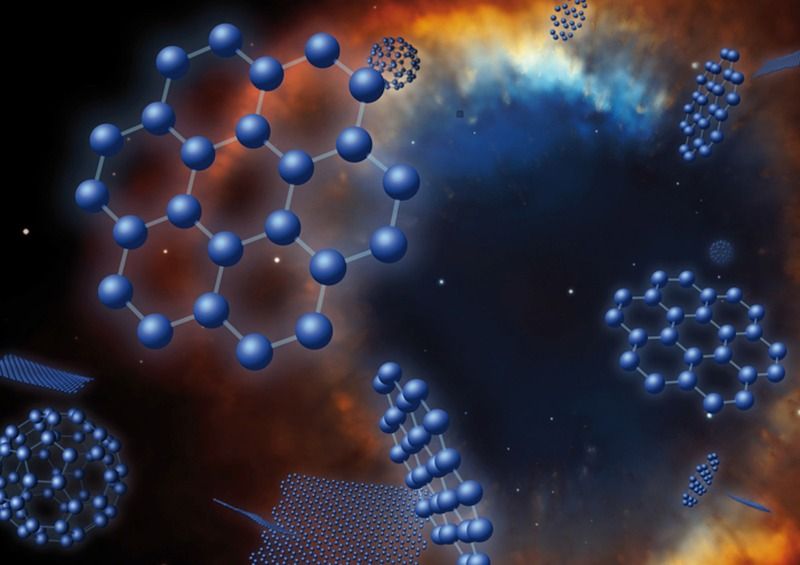

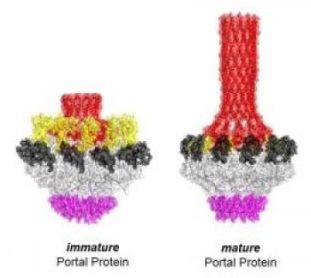

Interstellar molecular clouds are predominantly composed of hydrogen in molecular form (H2), but also contain a small percentage of dust particles mostly in the form of carbon nanostructures, called polyaromatic hydrocarbons (PAH). These clouds are often referred to as ‘star nurseries’ as their low temperature and high density allows gravity to locally condense matter in such a way that it initiates H fusion, the nuclear reaction at the heart of each star. Graphene-based materials, prepared from the exfoliation of graphite oxide, are used as a model of interstellar carbon dust as they contain a relatively large amount of atomic defects, either at their edges or on their surface. These defects are thought to sustain the Eley-Rideal chemical reaction, which recombines two H atoms into one H2 molecule.

The observation of interstellar clouds in inhospitable regions of space, including in the direct proximity of giant stars, poses the question of the origin of the stability of hydrogen in the molecular form (H2). This question stands because the clouds are constantly being washed out by intense radiation, hence cracking the hydrogen molecules into atoms. Astrochemists suggest that the chemical mechanism responsible for the recombination of atomic H into molecular H2 is catalysed by carbon flakes in interstellar clouds. Their theories are challenged by the need for a very efficient surface chemistry scenario to explain the observed equilibrium between dissociation and recombination. They had to introduce highly reactive sites into their models so that the capture of an atomic H nearby occurs without fail.