Storm-2657 exploits phishing and weak MFA to hijack HR SaaS accounts and redirect payroll funds.

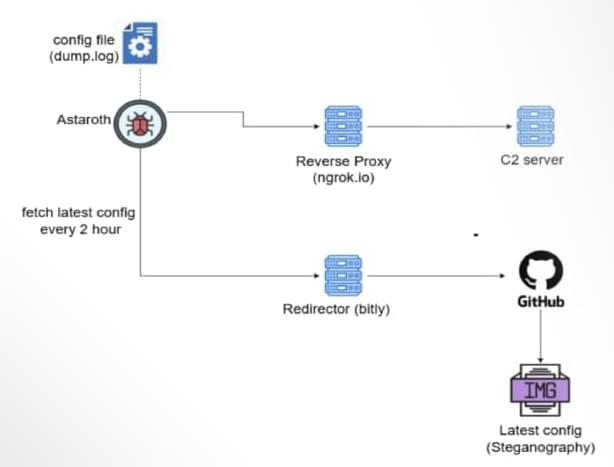

Cybersecurity researchers are calling attention to a new campaign that delivers the Astaroth banking trojan that employs GitHub as a backbone for its operations to stay resilient in the face of infrastructure takedowns.

“Instead of relying solely on traditional command-and-control (C2) servers that can be taken down, these attackers are leveraging GitHub repositories to host malware configurations,” McAfee Labs researchers Harshil Patel and Prabudh Chakravorty said in a report.

“When law enforcement or security researchers shut down their C2 infrastructure, Astaroth simply pulls fresh configurations from GitHub and keeps running.”

A large-scale botnet is targeting Remote Desktop Protocol (RDP) services in the United States from more than 100,000 IP addresses.

The campaign started on October 8 and based on the source of the IPs, researchers believe the attacks are launched by a multi-country botnet.

RDP is a network protocol that enables remote connection and control of Windows systems. It is typically used by administrators, helpdesk staff, and remote workers.

Google is updating the Chrome web browser to automatically revoke notification permissions for websites that haven’t been visited recently, to reduce alert overload.

While Google Chrome’s Safety Check tool already removes access to other permissions, such as location and camera, this new feature will extend this functionality to notifications on both desktop and Android versions of the browser.

The company said the new feature is designed to target sites that send frequent notifications that get little to no user interaction. According to Chrome product manager Archit Agarwal, although users receive a high volume of alerts, fewer than 1% of these notifications actually generate any engagement.

Microsoft is investigating an ongoing incident that is preventing some customers from accessing Microsoft 365 applications.

While the company has yet to share which regions are currently affected by this ongoing issue, it has been tagged as an incident in the admin center, a designation typically used for service issues with noticeable user impact.

According to a service alert seen by BleepingComputer, Redmond is currently reviewing telemetry data to discover the root cause and develop a fix.