Physicists at Florida State University (FSU) have uncovered a fascinating new phase of matter — a “ quantum pinball state” in which electrons act both as conductors and insulators at the same time. In this bizarre quantum regime, some electrons freeze into a rigid crystalline lattice while others move freely around them, much like balls ricocheting around fixed pins in a pinball machine. The discovery offers a new perspective on how quantum materials behave and could pave the way for breakthroughs in quantum computing, spintronics, and superconductivity.

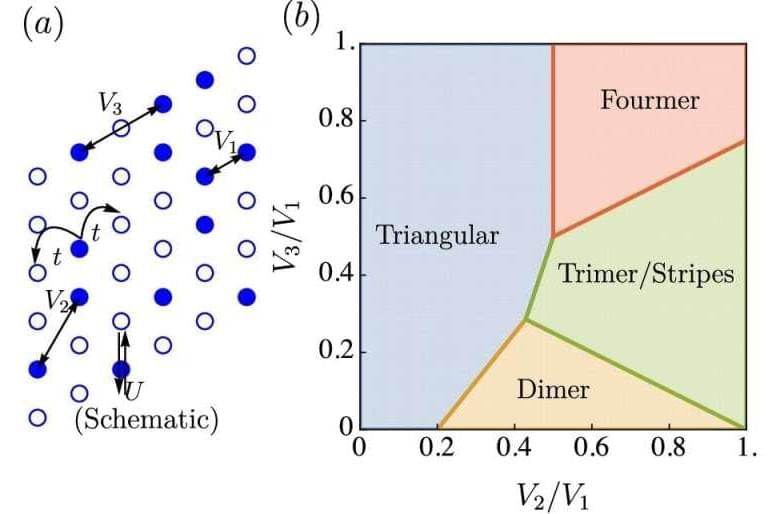

The research, published in npj Quantum Materials, was led by Dr. Aman Kumar, Prof. Hitesh Changlani, and Prof. Cyprian Lewandowski of FSU’s National High Magnetic Field Laboratory. Their study explores how electrons in a two-dimensional “moiré lattice” can transition between solid-like and liquid-like states under certain conditions, forming what physicists call a generalized Wigner crystal.