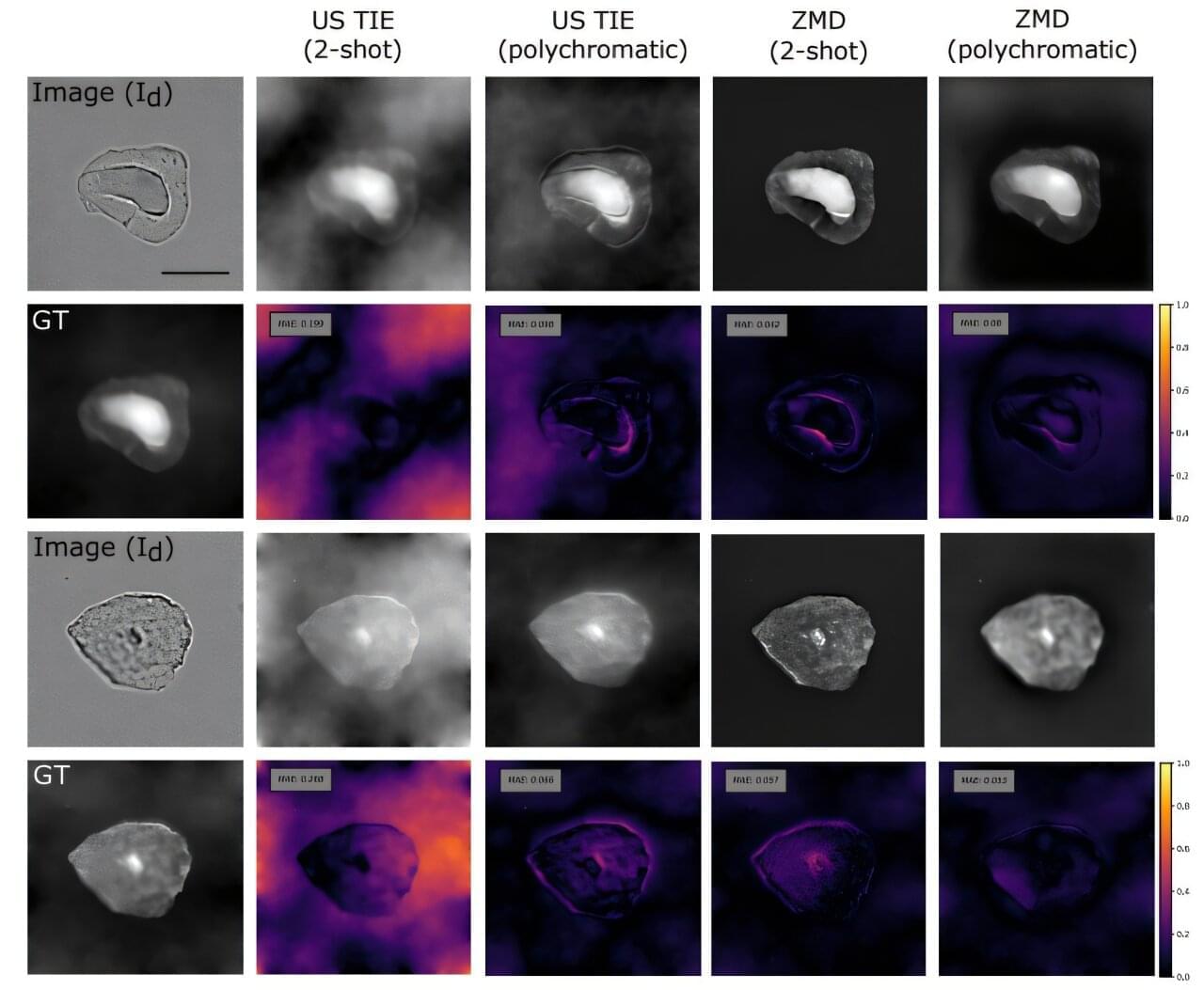

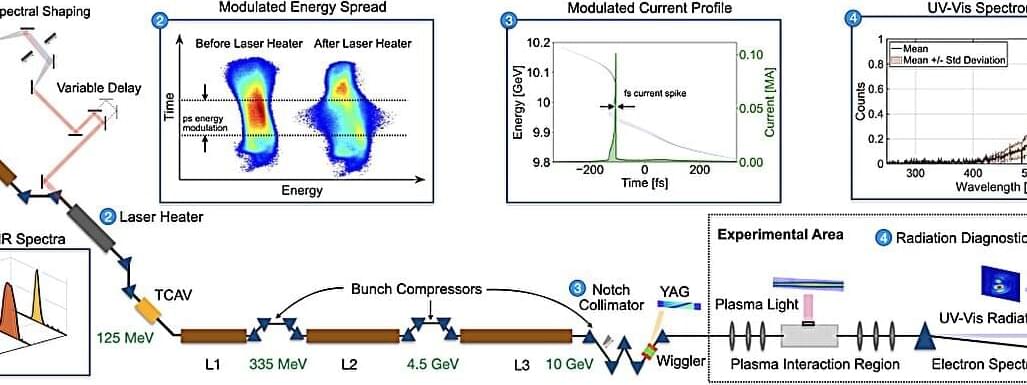

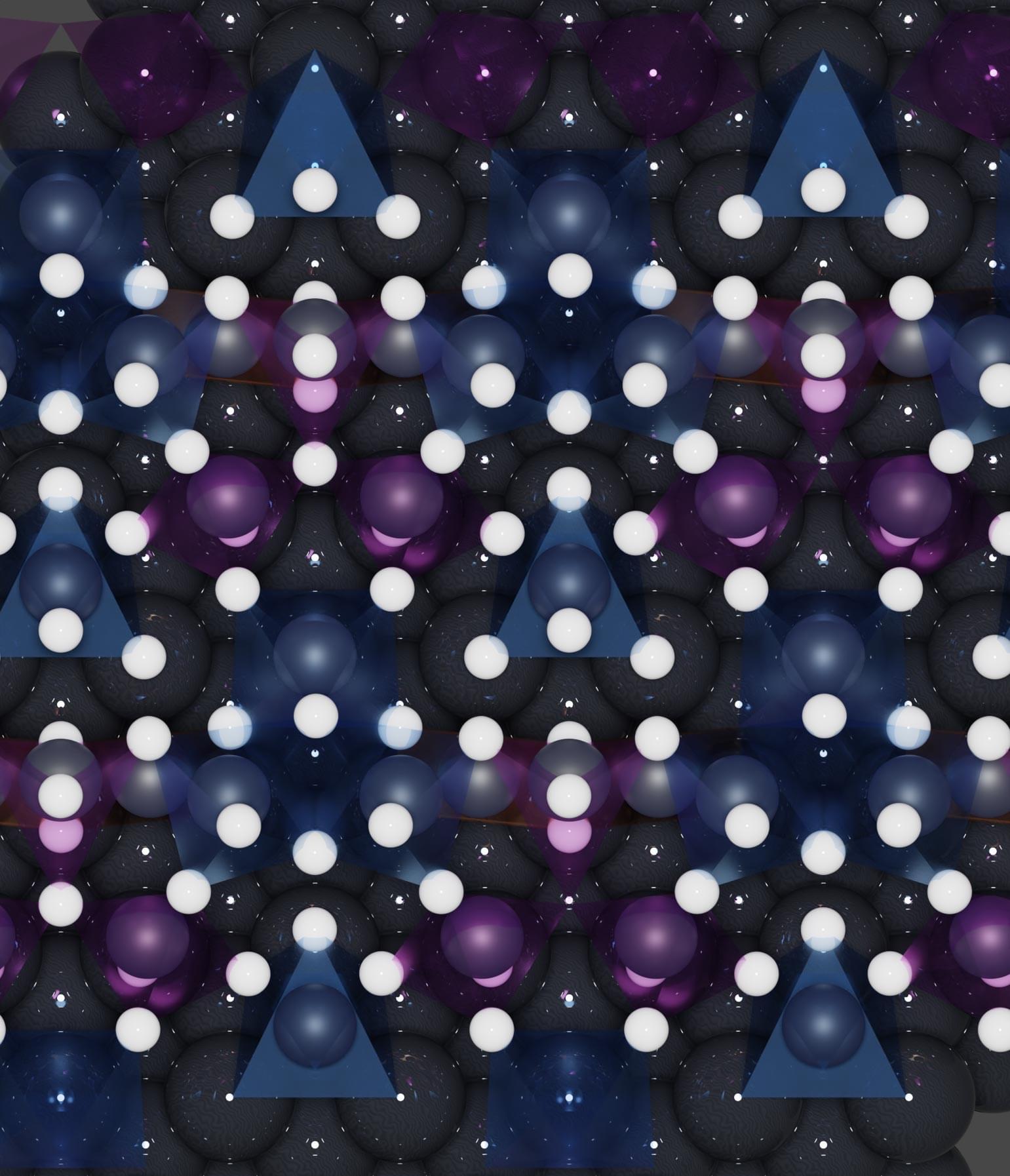

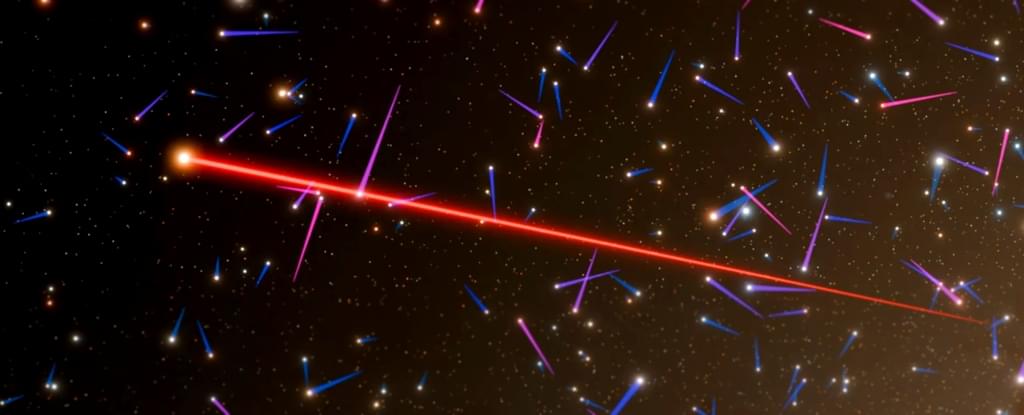

Lead-208 is the heaviest known doubly magic nucleus and its structure is therefore of special interest. Despite this magicity, which acts to provide a strong restorative force toward sphericity, it is known to exhibit both strong octupole correlations and some of the strongest quadrupole collectivity observed in doubly magic systems. In this Letter, we employ state-of-the-art experimental equipment to conclusively demonstrate, through four Coulomb-excitation measurements, the presence of a large, negative, spectroscopic quadrupole moment for both the vibrational octupole 3_1^- and quadrupole 2_1^+$ state, indicative of a preference for prolate deformation of the states.