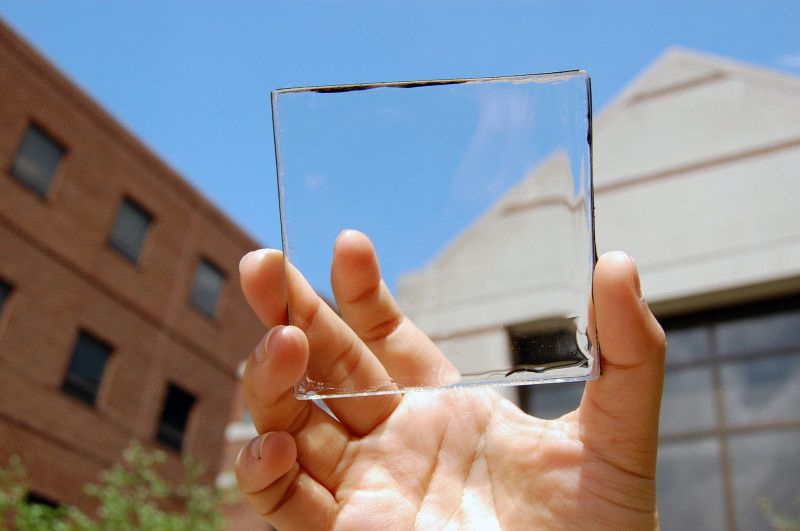

Back in August 2014, researchers at Michigan State University created a fully transparent solar concentrator, which could turn any window or sheet of glass (like your smartphone’s screen) into a photovoltaic solar cell. Unlike other “transparent” solar cells that we’ve reported on in the past, this one really is transparent, as you can see in the photos throughout this story. According to Richard Lunt, who led the research at the time, the team was confident the transparent solar panels can be efficiently deployed in a wide range of settings, from “tall buildings with lots of windows or any kind of mobile device that demands high aesthetic quality like a phone or e-reader.”

Now Ubiquitous Energy, an MIT startup we first reported on in 2013, is getting closer to bringing its transparent solar panels to market. Lunt cofounded the company and remains assistant professor of chemical engineering and materials science at Michigan State University. Essentially, what they’re doing is instead of shrinking the components, they’re changing the way the cell absorbs light. The cell selectively harvests the part of the solar spectrum we can’t see with our eye, while letting regular visible light pass through.

Scientifically, a transparent solar panel is something of an oxymoron. Solar cells, specifically the photovoltaic kind, make energy by absorbing photons (sunlight) and converting them into electrons (electricity). If a material is transparent, however, by definition it means that all of the light passes through the medium to strike the back of your eye. This is why previous transparent solar cells have actually only been partially transparent — and, to add insult to injury, they usually they cast a colorful shadow too.