Y. Sun et al. Route to a superconducting phase above room temperature in electron-doped hydride compounds under high pressure. Physical Review Letters. Vol. 123, August 30, 2019. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.123.097001.

Y. Sun et al. Route to a superconducting phase above room temperature in electron-doped hydride compounds under high pressure. Physical Review Letters. Vol. 123, August 30, 2019. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.123.097001.

Most of my professional life is centered on synthetic biology, an industry and movement to make biology easier to engineer. So far, this emerging discipline has yielded everything from living medicines and spider silk jackets to impossible hamburgers. But what will humankind be growing in the next century?

Credit: MIT Engineers from the MIT and Analog Devices have created the most complex chip design yet that uses transistors made of carbon nanotubes instead of silicon. The chip was manufactured using new technologies proven to work in a commercial chip-manufacturing facility.

The researchers seem to have chosen the RISC-V instruction set architecture (ISA) for the design of the chip, presumably due to the open source nature that didn’t require hassling with licensing restrictions and costs. The RISC-V processor handles 32-bit instructions and does 16-bit memory addressing. The chip is not meant to be used in mainstream devices quite yet, but it’s a strong proof of concept that can already run “hello world”-type applications.

One advantage transistors made out of carbon nanotubes have over silicon transistors is that they can be manufactured in multiple layers, allowing for very dense 3D chip designs. DARPA also believes that carbon nanotubes may allow for the manufacturing of future 3D chips that have performance similar or better than silicon chips, but they can also be manufactured for much lower costs.

Go to https://wix.com/go/Unbox to create your own website! Use code Unbox15 for 15% off a yearly premium plan!

Human Headphones are the World’s first true wireless over-ear headphones.

FOLLOW ME IN THESE PLACES FOR UPDATES

Twitter — http://twitter.com/unboxtherapy

Facebook — http://facebook.com/lewis.hilsenteger

Instagram — http://instagram.com/unboxtherapy

Ira Pastor, CEO, Bioquark Inc., Hosting The Regenerage Show — Episode 2 — “What Causes Biological Aging?”

Around the world, people are living longer — not just because child mortality is dropping, but also because we’re staying healthy for more years as we age. In the future, regenerative medicine and other new developments may help most people remain youthful much longer than they do today. In this talk, Aubrey de Grey, Chief Science Officer at the SENS Research Foundation, discusses the biology and sociology of what could be a massive shift in the way we live.

To learn more about effective altruism, visit effectivealtruism.org

This talk was filmed at EA Global 2019: San Francisco. You can learn more about these conferences at eaglobal.org

SUBSCRIBE to Barcroft TV: http://bit.ly/Oc61Hj

A DETERMINED TEENAGER with bionic arms champions diversity by showing the world it’s ‘cool to be different.’ Tilly Lockey, from County Durham, UK had both her arms amputated at 15 months old after contracting Group B meningococcal septicaemia. The 13-year-old was the first teenager in Britain to receive a pair of the 3D-printed bionic arms in 2016. Constantly in demand for her modelling work, Tilly extensively travels the world raising awareness for meningitis — the condition which almost took her life as a baby. Follow her story here:

https://www.instagram.com/tilly.lockey/

https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC5hrVolbwN8XsWbNTRpoIMA

Barcroft TV would like to thank Debbie Todd for her photography in this video: https://www.instagram.com/debbietoddphotographer

Video Credits:

Videographer / director: Ian Paine

Producer: Gareth Shoulder, Ruby Coote

Editor: Ciara Cecil

Click here to follow your favourite Barcroft shows on Instagram!

Barcroft TV — https://www.instagram.com/barcroft_tv/

Born Different — https://www.instagram.com/borndifferentshow/

Shake My Beauty — https://www.instagram.com/shakemybeauty/

Hooked On The Look — https://www.instagram.com/hookedonthelookshow/

Beast Buddies — https://www.instagram.com/beastbuddiesshow/

Ridiculous Rides — https://www.instagram.com/ridiculousridesshow/

Snapped In The Wild — https://www.instagram.com/snappedinthewild/

Dog Dynasty — https://www.instagram.com/dogdynastyshow/

For more amazing content, click here!

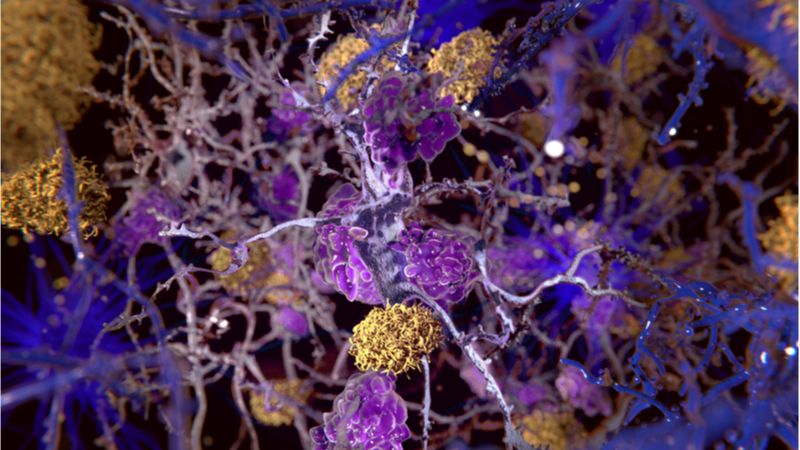

The macrophages resident in the brain and spinal cord appear to be a key element in the progression of Alzheimer’s disease, according to the results of a new mouse study.

Microglial mayhem

As we age, our immune cells become increasingly dysfunctional; once-helpful cells can behave in harmful ways, promoting persistent inflammation, impairing tissue regeneration, and possibly also facilitating the progression of age-related diseases.

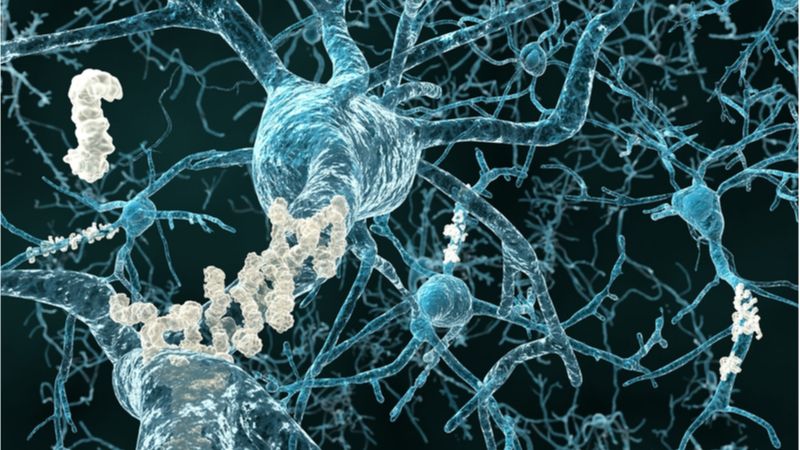

In a recent study, a team of researchers has discovered that a naturally occurring protein called Lipocalin-type prostaglandin D synthase (L-PGDS) prevents, and can destroy, the protein aggregates associated with Alzheimer’s disease.

Surprisingly common and with critical functions

L-PGDS is a common protein, second only to albumin, in the human brain. It provides several critical functions, including regulation of processes and protection against further damage from ischemic strokes. It has been shown to be a molecular chaperone, preventing amyloid beta from forming the deadly aggregates associated with Alzheimer’s, and, perhaps most importantly, it has been shown to destroy aggregates that already exist. Not surprisingly, people who suffer from Alzheimer’s disease lack adequate amounts of this critical protein.