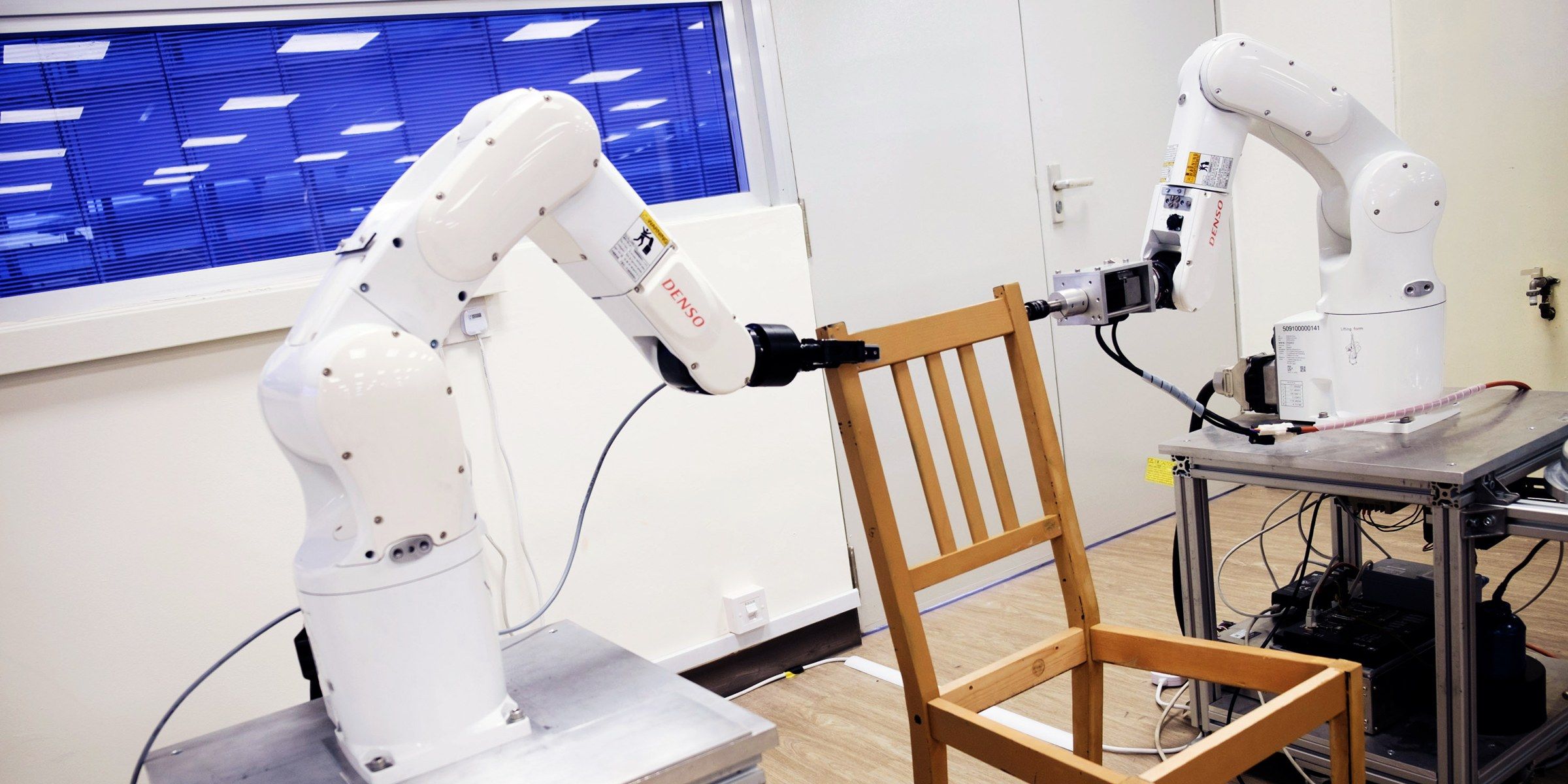

And just like that, humanity draws one step closer to the singularity, the moment when the machines grow so advanced that humans become obsolete: A robot has learned to autonomously assemble an Ikea chair without throwing anything or cursing the family dog.

Researchers report today in Science Robotics that they’ve used entirely off-the-shelf parts—two industrial robot arms with force sensors and a 3D camera—to piece together one of those Stefan Ikea chairs we all had in college before it collapsed after two months of use. From planning to execution, it only took 20 minutes, compared to the human average of a lifetime of misery. It may all seem trivial, but this is in fact a big deal for robots, which struggle mightily to manipulate objects in a world built for human hands.

To start, the researchers give the pair of robot arms some basic instructions—like those cartoony illustrations, but in code. This piece goes first into this other piece, then this other, etc. Then they place the pieces in a random pattern front of the robots, which eyeball the wood with the 3D camera. So the researchers give the robots a list of tasks, then the robots take it from there.