Artificial Intelligence (AI) is, without a doubt, the defining technological breakthrough of our time. It represents not only a quantum leap in our ability to solve complex problems but also a mirror reflecting our ambitions, fears, and ethical dilemmas. As we witness its exponential growth, we cannot ignore the profound impact it is having on society. But are we heading toward a bright future or a dangerous precipice?

This opinion piece aims to foster critical reflection on AI’s role in the modern world and what it means for our collective future.

AI is no longer the stuff of science fiction. It is embedded in nearly every aspect of our lives, from the virtual assistants on our smartphones to the algorithms that recommend what to watch on Netflix or determine our eligibility for a bank loan. In medicine, AI is revolutionizing diagnostics and treatments, enabling the early detection of cancer and the personalization of therapies based on a patient’s genome. In education, adaptive learning platforms are democratizing access to knowledge by tailoring instruction to each student’s pace.

These advancements are undeniably impressive. AI promises a more efficient, safer, and fairer world. But is this promise being fulfilled? Or are we inadvertently creating new forms of inequality, where the benefits of technology are concentrated among a privileged few while others are left behind?

One of AI’s most pressing challenges is its impact on employment. Automation is eliminating jobs across various sectors, including manufacturing, services, and even traditionally “safe” fields such as law and accounting. Meanwhile, workforce reskilling is not keeping pace with technological disruption. The result? A growing divide between those equipped with the skills to thrive in the AI-driven era and those displaced by machines.

Another urgent concern is privacy. AI relies on vast amounts of data, and the massive collection of personal information raises serious questions about who controls these data and how they are used. We live in an era where our habits, preferences, and even emotions are continuously monitored and analyzed. This not only threatens our privacy but also opens the door to subtle forms of manipulation and social control.

Then, there is the issue of algorithmic bias. AI is only as good as the data it is trained on. If these data reflect existing biases, AI can perpetuate and even amplify societal injustices. We have already seen examples of this, such as facial recognition systems that fail to accurately identify individuals from minority groups or hiring algorithms that inadvertently discriminate based on gender. Far from being neutral, AI can become a tool of oppression if not carefully regulated.

Who Decides What Is Right?

AI forces us to confront profound ethical questions. When a self-driving car must choose between hitting a pedestrian or colliding with another vehicle, who decides the “right” choice? When AI is used to determine parole eligibility or distribute social benefits, how do we ensure these decisions are fair and transparent?

The reality is that AI is not just a technical tool—it is also a moral one. The choices we make today about how we develop and deploy AI will shape the future of humanity. But who is making these decisions? Currently, AI’s development is largely in the hands of big tech companies and governments, often without sufficient oversight from civil society. This is concerning because AI has the potential to impact all of us, regardless of our individual consent.

A Utopia or a Dystopia?

The future of AI remains uncertain. On one hand, we have the potential to create a technological utopia, where AI frees us from mundane tasks, enhances productivity, and allows us to focus on what truly matters: creativity, human connection, and collective well-being. On the other hand, there is the risk of a dystopia where AI is used to control, manipulate, and oppress—dividing society between those who control technology and those who are controlled by it.

The key to avoiding this dark scenario lies in regulation and education. We need robust laws that protect privacy, ensure transparency, and prevent AI’s misuse. But we also need to educate the public on the risks and opportunities of AI so they can make informed decisions and demand accountability from those in power.

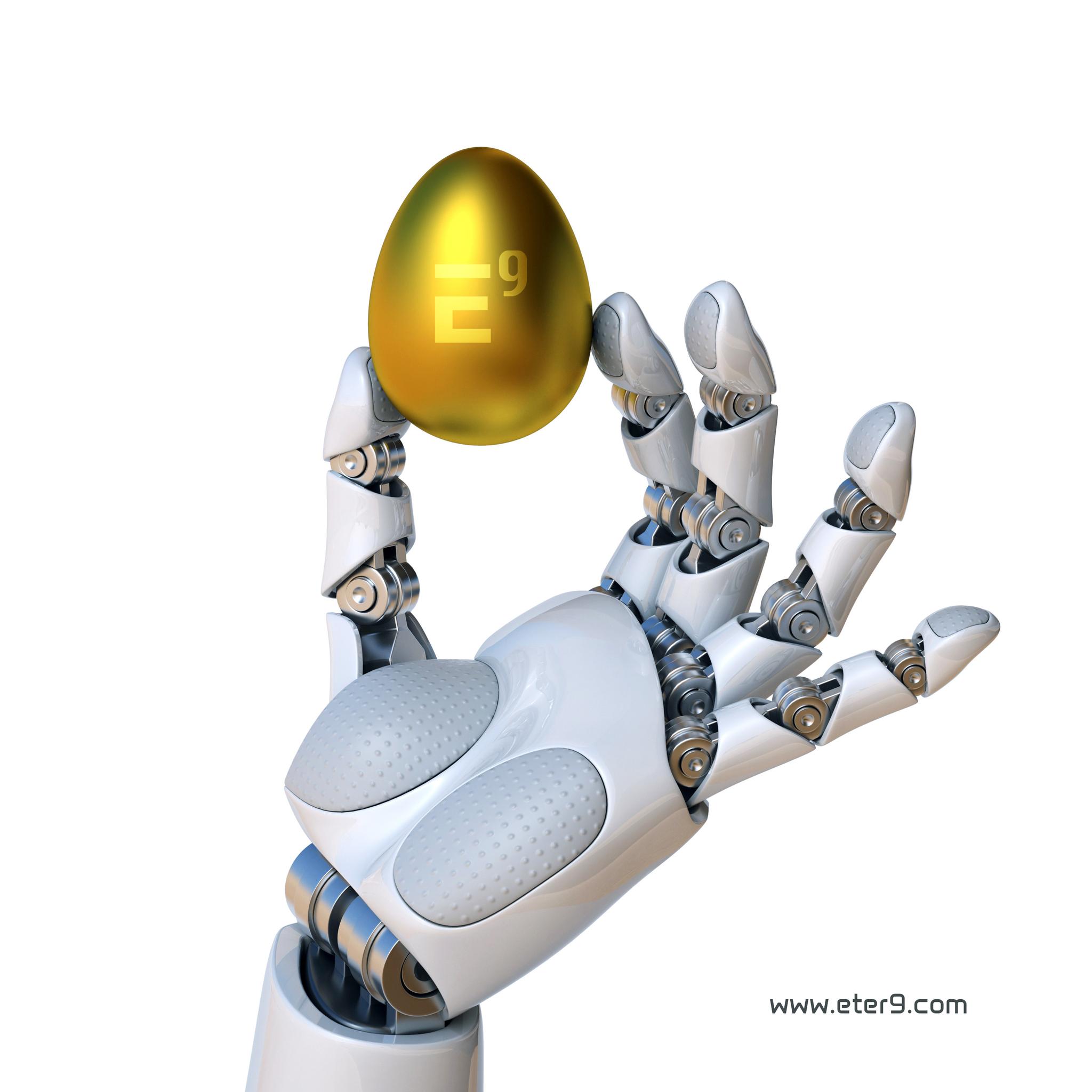

Artificial Intelligence is, indeed, the Holy Grail of Technology. But unlike the medieval legend, this Grail is not hidden in a distant castle—it is in our hands, here and now. It is up to us to decide how we use it. Will AI be a tool for building a more just and equitable future, or will it become a weapon that exacerbates inequalities and threatens our freedom?

The answer depends on all of us. As citizens, we must demand transparency and accountability from those developing and implementing AI. As a society, we must ensure that the benefits of this technology are shared by all, not just a technocratic elite. And above all, we must remember that technology is not an end in itself but a means to achieve human progress.

The future of AI is the future we choose to build. And at this critical moment in history, we cannot afford to get it wrong. The Holy Grail is within our reach—but its true value will only be realized if we use it for the common good.

__

Copyright © 2025, Henrique Jorge

[ This article was originally published in Portuguese in SAPO’s technology section at: https://tek.sapo.pt/opiniao/artigos/o-santo-graal-da-tecnologia ]