In advance of a star called T Coronae Borealis (T CrB) or the “Blaze Star” exploding in a very rare event, NASA is advising sky-watchers to get to know its constellation.

Tesla is ramping up production of its Semi trucks to 50,000 units annually by 2026, while enhancing performance, charging infrastructure, and electrification solutions to support the transition from diesel ## ## Questions to inspire discussion ## Production and Delivery.

🏭 Q: When will Tesla Semi production and deliveries begin? A: Tesla Semi customer deliveries will start in 2026, with production ramping throughout the year to reach a goal of 50,000 units/year at the Nevada plant.

🚚 Q: What are the key features of the new Tesla Semi? A: The Tesla Semi offers 500 mile long range and 300 mile standard range options, with improved mirror design, better sight lines, enhanced aerodynamics, and drop glass for easier driver interaction. Technology and Efficiency.

🔋 Q: How does the new HP battery improve the Tesla Semi? A: The new HP battery is cheaper to manufacture, maintains the same range with less battery energy, and achieves over 7% efficiency improvements, creating a positive feedback loop for cost and weight reduction.

⚡ Q: What is the e-PTO feature in the Tesla Semi? A: The electric power takeoff (EPTO) enables support for longer combinations, more trailer equipment, and helps electrify additional pieces of equipment, facilitating broader industry transition to electric solutions. Charging Infrastructure.

🔌 Q: What charging solutions is Tesla developing for the Semi? A: Tesla is building a publicly available charging network with 46 sites along truck routes and in major industrial areas, including stations at truck stops, to ensure low-cost, reliable, and available charging for every semi.

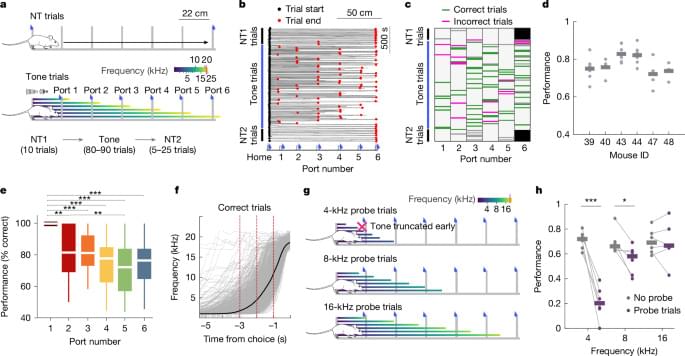

Is the nearest galaxy to ours being torn apart? Research suggests so. A team led by Satoya Nakano and Kengo Tachihara at Nagoya University in Japan has revealed new insights into the motion of massive stars in the Small Magellanic Cloud (SMC), a small galaxy neighboring the Milky Way. Their findings suggest that the gravitational pull of the Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC), the SMC’s larger companion, may be tearing the smaller one apart. This discovery reveals a new pattern in the motion of these stars that could transform our understanding of galaxy evolution and interactions. The results were published in The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series.

“When we first got this result, we suspected that there might be an error in our method of analysis,” Tachihara said. “However, upon closer examination, the results are indisputable, and we were surprised.”

The SMC remains one of the closest galaxies to the Milky Way. This proximity allowed the research team to identify and track approximately 7,000 massive stars within the galaxy. These stars, which are over eight times the mass of our Sun, typically survive for only a few million years before exploding as supernovae. Their presence indicates regions rich in hydrogen gas, a crucial component of star formation.

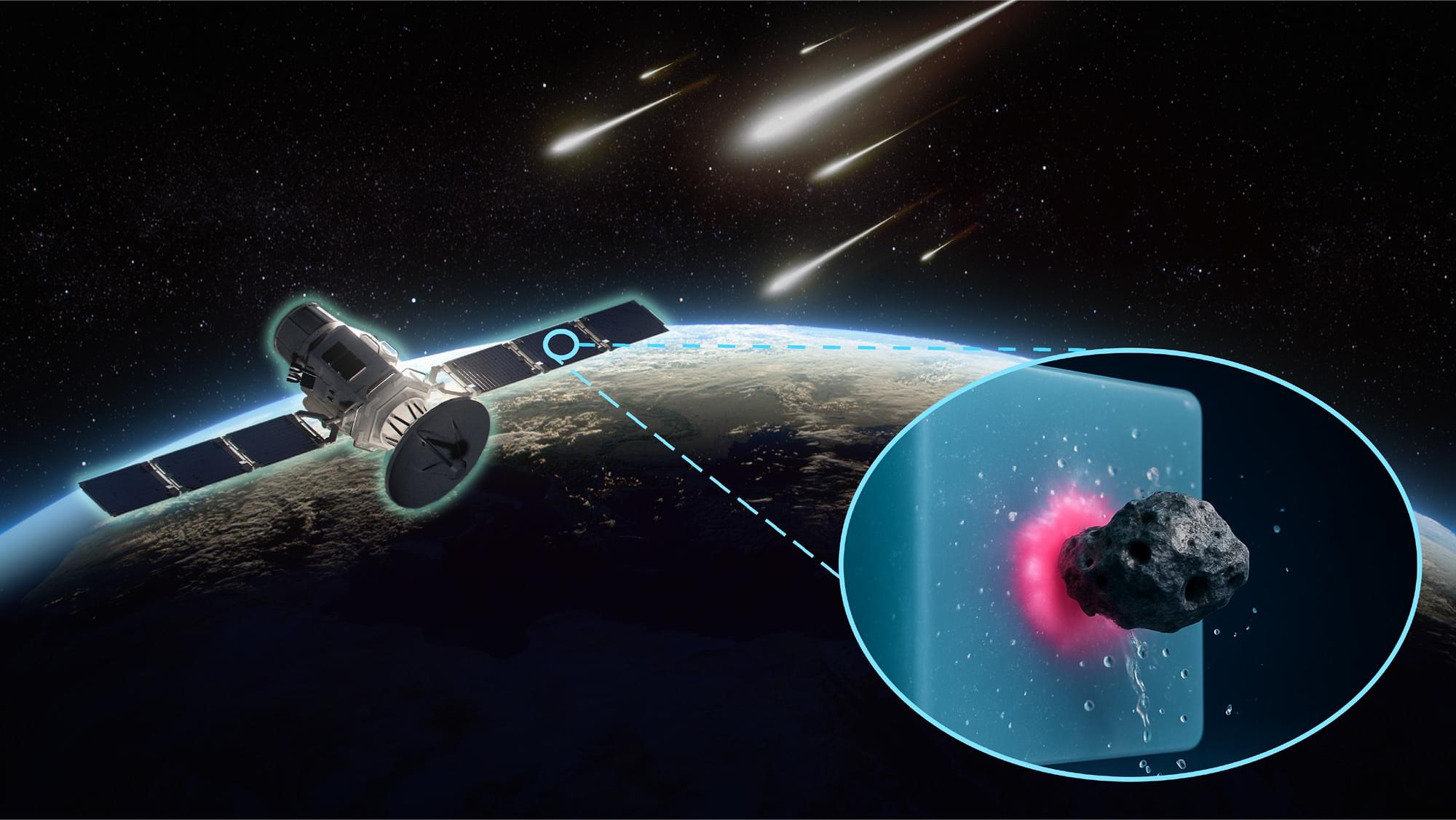

What if there were a fabric that, like Superman, could take a bullet and self-heal? Such a super-dynamic, action-powered polymer might actually help protect real-life flyers in space.

Material scientists at Texas A&M University have developed just such a polymer with a unique self-healing property never before seen at any scale. When struck by a projectile, this material stretches so much that when the projectile manages to pass through, it takes only a small amount of the polymer with it. As a result, the hole left behind is much smaller than the projectile itself.

However, for now, this effect has only been observed under extreme temperatures and at the nanoscale.

A UNSW Sydney mathematician has discovered a new method to tackle algebra’s oldest challenge—solving higher polynomial equations.

Polynomials are equations involving a variable raised to powers, such as the degree two polynomial: 1 + 4x – 3x2 = 0.

The equations are fundamental to math as well as science, where they have broad applications, like helping describe the movement of planets or writing computer programs.

A theoretical study by RIKEN physicists, published in Physics Letters B, has accurately determined the interaction between a charmonium and a proton or neutron for the first time.

From two galaxies colliding to an electron jettisoned from a nucleus, all interactions in the universe can be described in terms of just four fundamental forces.

Gravity and the electromagnetic force are the two we are familiar with in everyday life, while the weak and strong forces operate over minuscule distances—roughly the size of an atomic nucleus or smaller.

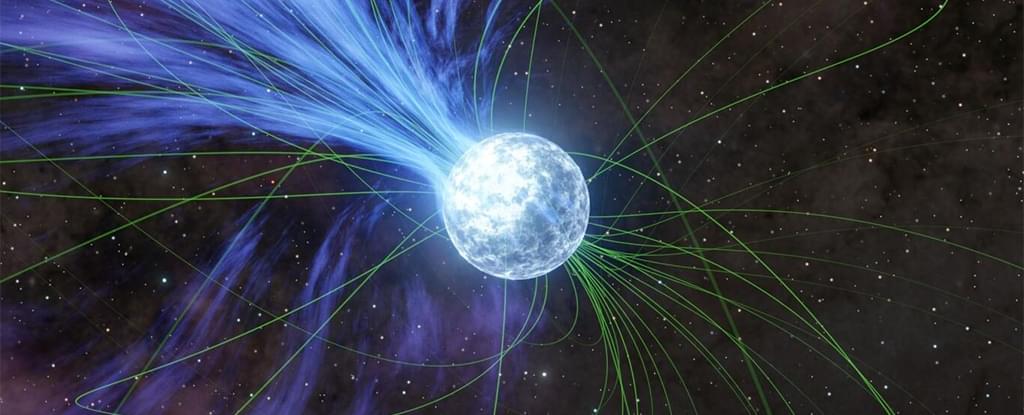

Scientists have long been trying to determine how elements heavier than iron, including gold and platinum, were first created and scattered through the Universe, and new research may give us another part of the answer: magnetars.

Rare, giant flares erupting from these highly magnetized neutron stars could contribute to the production of the heavy elements, based on a fresh analysis of a magnetar burst captured in 2004.

The full story of that burst wasn’t understood at the time. The latest work, from an international team of scientists, suggests the flash of gamma ray light captured back then originated from heavy elements being shot out into space.

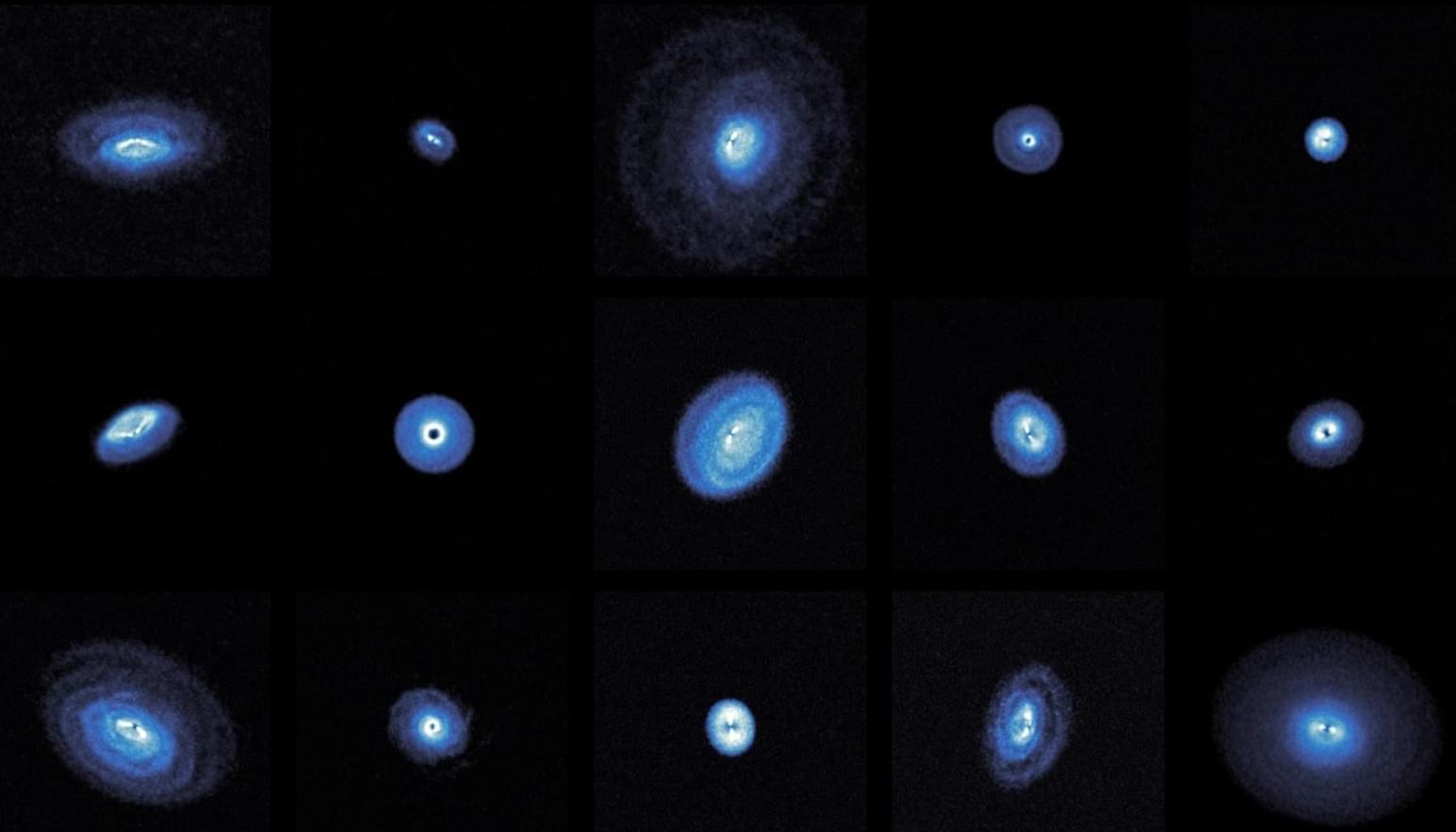

Using ALMA, Teague’s team captured images of 15 young star systems sprinkled in space between a few hundred to 1,000 light-years from Earth. Rather than rely on direct detection of a young planet’s faint light, Teague’s team looked for the subtle clues these infant worlds imprint on their surroundings — such as gaps and rings in dusty disks, swirling gas motions caused by a planet’s gravity, and other physical disturbances that hint at a planet’s presence. To uncover these signatures, the researchers used ALMA to map the motion of gas within over a dozen protoplanetary disks.

“It’s like trying to spot a fish by looking for ripples in a pond, rather than trying to see the fish itself,” Christophe Pinte, an astrophysicist at the Institute for Planetary sciences and Astrophysics in France, who was also a principal investigator of the project, said in the statement.