A quick overview of some of the most popular fictional architectural styles.

Which style did I miss? Let me know down below 👇

Please like and subscribe if you enjoyed this video. It helps a lot!

If you want to support me even more, consider becoming a member: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCsaIQHXEMymxrg4tMUkwJ1g/join.

00:00 Cyberpunk.

00:37 Steampunk.

01:14 Dieselpunk.

01:46 Atompunk.

02:22 Solarpunk.

02:58 Biopunk.

03:33 Post-Apocalyptic Salvagecore.

04:07 Brutalist Dystopia.

04:40 Arcology.

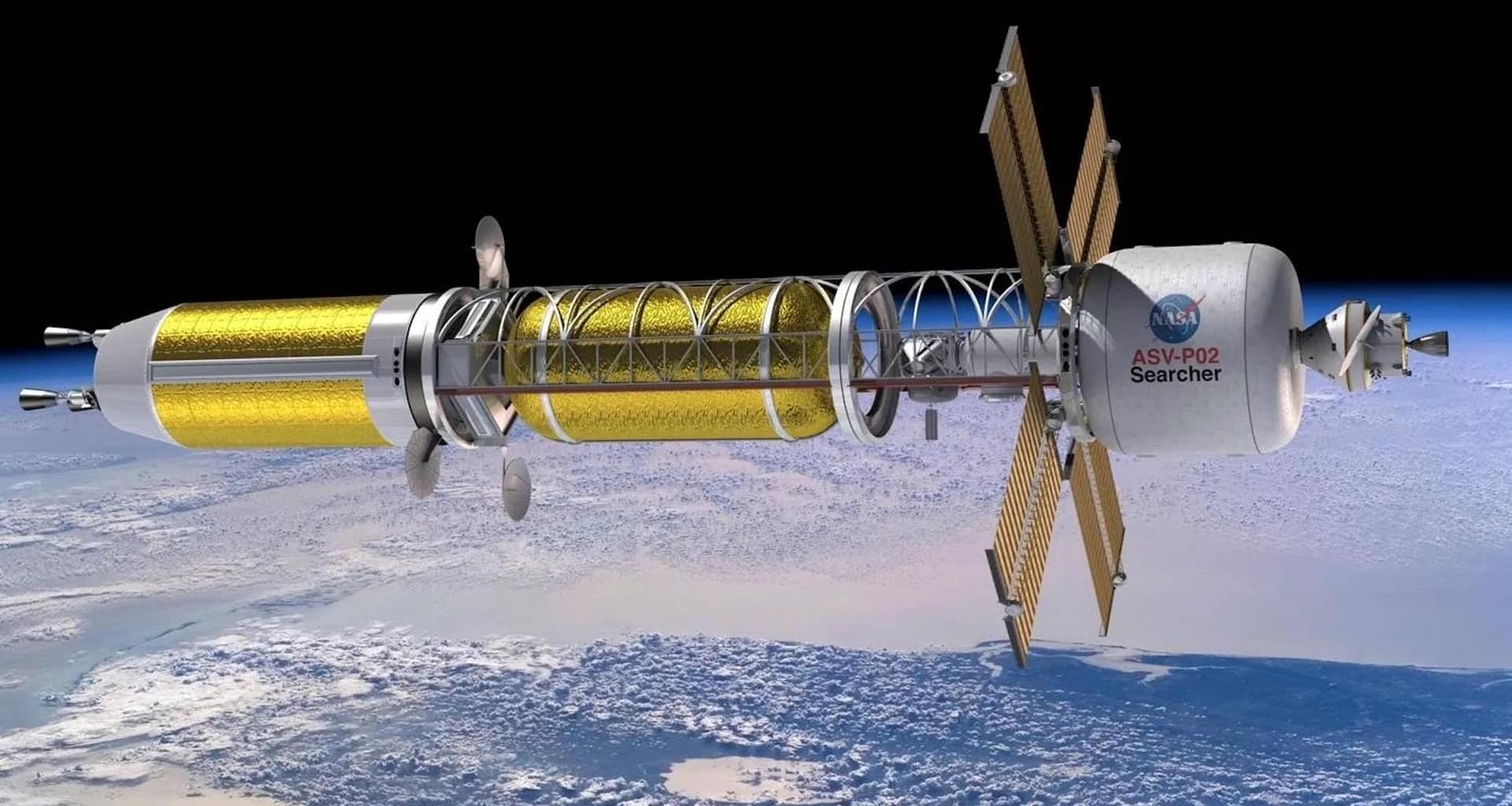

05:16 Space-Opera Modernism.

05:52 Dark Fantasy.

06:25 Clockpunk.

06:58 Teslapunk.

07:29 Afrofuturist.

08:02 Subnautical Artifice