In this edition of Inverse Daily, read stories about how far the James Webb Space Telescope has gone, why Axiom Space is building the station of the future, and more.

Category: space – Page 603

Mysterious Cosmic “Spider” Found To Be Source of Powerful Gamma-Rays

Investigated by the SOAR Telescope operated by NOIRLab, the binary system is the first to be found at the penultimate stage of its evolution. Using the 4.1-meter SOAR Telescope in Chile, astronomers have discovered the first example of a binary system where a star in the process of becoming a white.

MIT physicists and colleagues have discovered the “secret sauce” behind some of the exotic properties of a new quantum material that has transfixed physicists due to those properties, which include superconductivity. Although theorists had predicted the reason for the unusual properties of the material, known as a kagome metal, this is the first time that the phenomenon behind those properties has been observed in the laboratory.

A 1,000 light year bubble unveils link between supernovae and new stars

The Buddha once described our world as “a star at dawn, a bubble in a stream.”

By chance, our Sun wandered into the middle of a cosmic bubble 5 million years ago. Astronomers now know that gave us front row seats to the star formation show.

A massive asteroid will zip past Earth next week. Here’s how to spot it

An enormous asteroid more massive than two Empire State Buildings is heading our way, but unlike the so-called planet-killer comet in the recent movie “Don’t Look Up,” this space rock will zoom harmlessly past Earth.

The stony asteroid, known as (7482) 1994 PC1, will pass at its closest on Jan. 18 at 4:51 p.m. EST (2151 GMT), traveling at 43,754 mph (70,415 km/h) and hurtling past Earth at a distance of 0.01324 astronomical units — 1.2 million miles (nearly 2 million kilometers), according to NASA JPL-Caltech’s Solar System Dynamics (SSD).

Adriano V. Autino — a lecture on Space Philosophy at International Space University, Strasburgh

As an invited lecturer, was giving a lecture on Space Renaissance Philosophy at the International Space University, Strasburgh, the January 11th 2022, in the Auditorium.

Woodside pitches massive solar and battery plant, minuscule dent in emissions

Oil and gas giant submits plans for up to 500MW of solar and battery storage to supply renewable power to industrial customers — including its own LNG operations — in WA Pilbara region.

Oil and gas giant Woodside has kicked off the new year by firming up plans to develop a massive solar and battery project in Western Australia’s Pilbara region, to supply renewable electricity to local industrial customers, including its own Pluto LNG facility.

In a submission to the W.A. Environmental Protection Authority on Monday, the company proposed the Woodside Solar Facility to be built in 100MW phases to a total capacity of up to 500MW, ultimately comprising around 1,000,000 solar panels and including battery energy storage infrastructure of up to 400MWh.

Woodside confirmed in its proposal that the solar farm and battery would deliver solar power to customers on the Burrup Peninsula, including at the Maitland Industrial Park, and likely including the company’s own onshore Pluto gas processing plant.

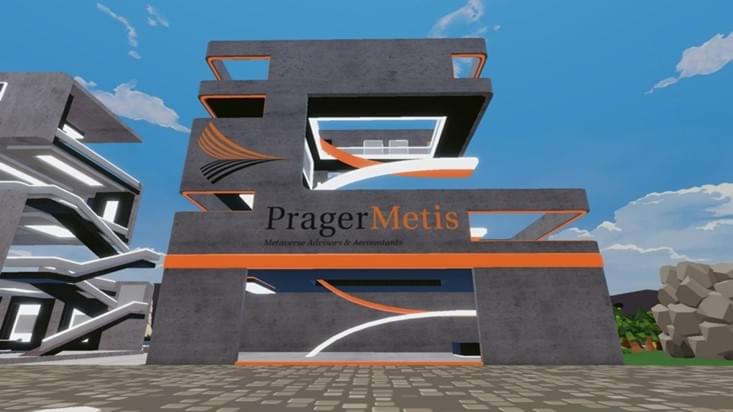

Prager Metis sets up first CPA firm in metaverse

Prager Metis has become the first CPA firm to open up a metaverse headquarters. The firm, which in real life is based in New York, is setting up shop in Decentraland, a 3D virtual world, as part of a joint venture with Banquet LLC, a metaverse studio.

The firm purchased the piece of virtual real estate on Dec. 28, a three-story digital structure. On the first floor is an open floor plan that doubles as a gallery space for nonfungible tokens from Prager Metis clients along with a large entertainment area. The second floor will provide more of a working space with meeting rooms and conference capabilities. The third floor will serve as a rooftop space where Prager Metis intends to host events and even live entertainment.

The metaverse has been attracting attention ever since Facebook’s parent company announced a name change last October to Meta to highlight its interest in developing technology for virtual reality and augmented reality. More businesses have followed suit in setting up shop in the metaverse. Prager Metis isn’t the first firm to dip its toes in the waters: PricewaterhouseCoopers’ Hong Kong firm announced last month that it had bought virtual land on another metaverse platform, the Sandbox, but Prager Metis is going further by setting up an actual headquarters in Decentraland. It plans to focus on advisory services for clients and potentially for other accounting firms as well. The firm already has clients who have entered the rapidly growing market for nonfungible tokens, or NFTs, which use blockchain technology to create collectibles and artwork that people bid on to buy and trade.

Research Shows Gravitational Action of Sun and Moon Influences Behavior of Plants and Animals

Research conducted at the University of Campinas in Brazil was driven by observations of fluctuations in autoluminescence caused by seed germination in cycles regulated by gravitational tides.

The rhythms of activity in all biological organisms, both plants and animals, are closely linked to the gravitational tides created by the orbital mechanics of the Sun-Earth-Moon system. This truth has been somewhat neglected by scientific research but is foregrounded in a study by Cristiano de Mello Gallep at the University of Campinas (UNICAMP) in the state of São Paulo, Brazil, and Daniel Robert at the University of Bristol in the United Kingdom. An article on the study is published in the Journal of Experimental Botany.

“All matter on Earth, both live and inert, experiences the effects of the gravitational forces of the Sun and Moon expressed in the form of tides. The periodic oscillations exhibit two daily cycles and are modulated monthly and annually by the motions of these two celestial bodies. All organisms on the planet have evolved in this context. What we sought to show in the article is that gravitational tides are a perceptible and potent force that has always shaped the rhythmic activities of these organisms,” Gallep told Agência FAPESP.

Scientists Say the Universe Itself May Be “Pixelated”

Here’s a brain teaser for you: scientists are suggesting spacetime may be made out of individual “spacetime pixels,” instead of being smooth and continuous like it seems.

Rana Adhikari, a professor of physics at Caltech, suggested in a new press blurb that these pixels would be “so small that if you were to enlarge things so that it becomes the size of a grain of sand, then atoms would be as large as galaxies.”

Adhikari’s goal is to reconcile the conventional laws of physics, as determined by general relativity, with the more mysterious world of quantum physics.