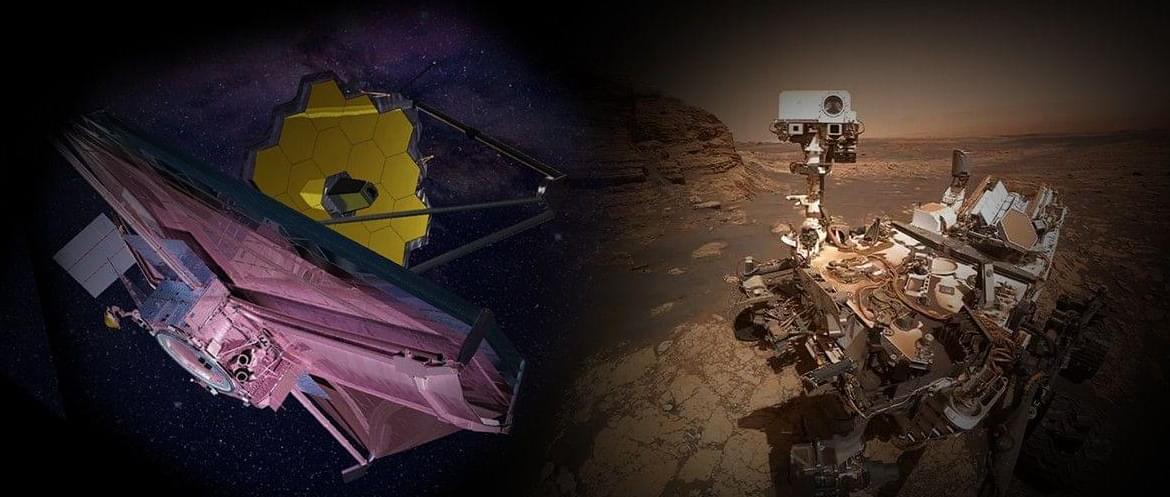

Two icons of discovery, NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope and NASA’s Curiosity rover, have earned places in TIME’s “Best Inventions Hall of Fame,” which recognizes the 25 groundbreaking inventions of the past quarter century that have had the most global impact, since TIME began its annual Best Inventions list in 2000. The inventions are celebrated in TIME’s December print issue.

“NASA does the impossible every day, and it starts with the visionary science that propels humanity farther than ever before,” said Nicky Fox, associate administrator, Science Mission Directorate, NASA Headquarters in Washington. “Congratulations to the teams who made the world’s great engineering feats, the James Webb Space Telescope and the Mars Curiosity Rover, a reality. Through their work, distant galaxies feel closer, and the red sands of Mars are more familiar, as they expanded and redefined the bounds of human achievement in the cosmos for the benefit of all.”

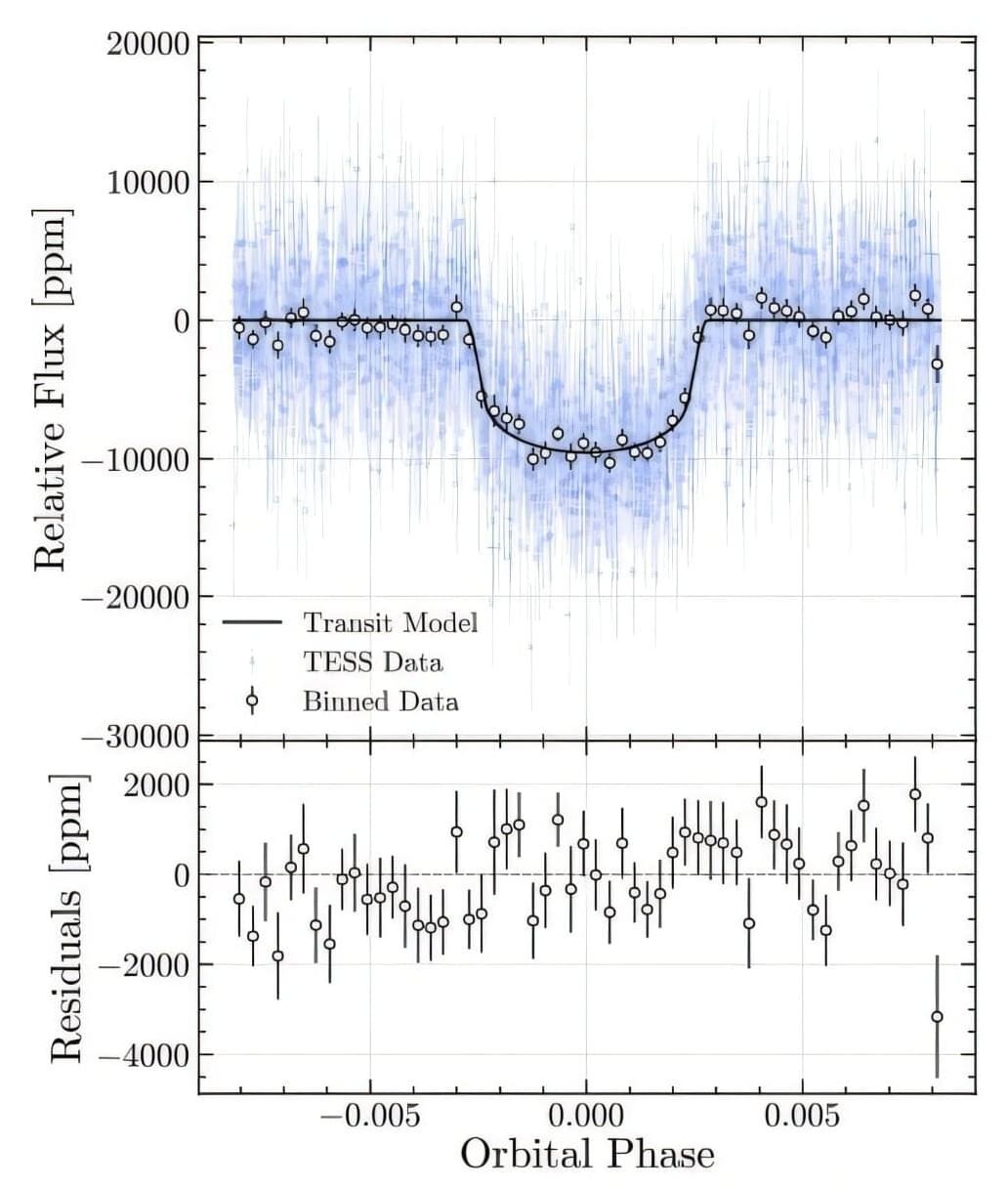

Decades in the making and operating a million miles from Earth, Webb is the most powerful space telescope ever built, giving humanity breathtaking views of newborn stars, distant galaxies, and even planets orbiting other stars. The new technologies developed to enable Webb’s science goals – from optics to detectors to thermal control systems – now also touch Americans’ everyday lives, improving manufacturing for everything from high-end cameras and contact lenses to advanced semiconductors and inspections of aircraft engine components.