The advent of quantum simulators in various platforms8,9,10,11,12,13,14 has opened a powerful experimental avenue towards answering the theoretical question of thermalization5,6, which seeks to reconcile the unitarity of quantum evolution with the emergence of statistical mechanics in constituent subsystems. A particularly interesting setting is that in which a quantum system is swept through a critical point15,16,17,18, as varying the sweep rate can allow for accessing markedly different paths through phase space and correspondingly distinct coarsening behaviour. Such effects have been theoretically predicted to cause deviations19,20,21,22 from the celebrated Kibble–Zurek (KZ) mechanism, which states that the correlation length ξ of the final state follows a universal power-law scaling with the ramp time tr (refs. 3, 23,24,25).

Whereas tremendous technical advancements in quantum simulators have enabled the observation of a wealth of thermalization-related phenomena26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35, the analogue nature of these systems has also imposed constraints on the experimental versatility. Studying thermalization dynamics necessitates state characterization beyond density–density correlations and preparation of initial states across the entire eigenspectrum, both of which are difficult without universal quantum control36. Although digital quantum processors are in principle suitable for such tasks, implementing Hamiltonian evolution requires a high number of digital gates, making large-scale Hamiltonian simulation infeasible under current gate errors.

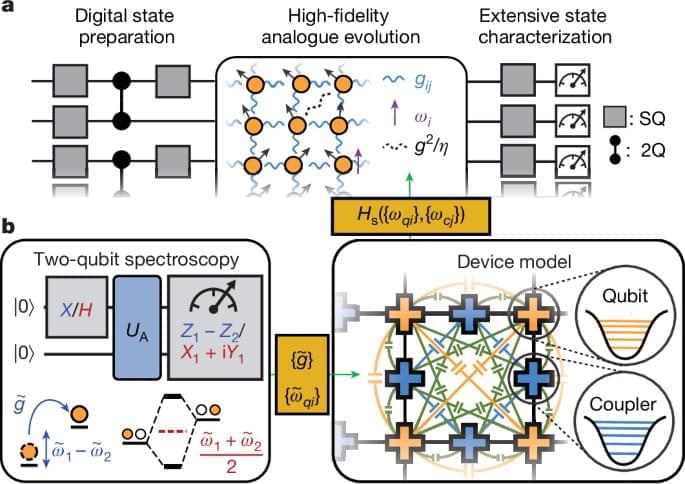

In this work, we present a hybrid analogue–digital37,38 quantum simulator comprising 69 superconducting transmon qubits connected by tunable couplers in a two-dimensional (2D) lattice (Fig. 1a). The quantum simulator supports universal entangling gates with pairwise interaction between qubits, and high-fidelity analogue simulation of a U symmetric spin Hamiltonian when all couplers are activated at once. The low analogue evolution error, which was previously difficult to achieve with transmon qubits due to correlated cross-talk effects, is enabled by a new scalable calibration scheme (Fig. 1b). Using cross-entropy benchmarking (XEB)39, we demonstrate analogue performance that exceeds the simulation capacity of known classical algorithms at the full system size.