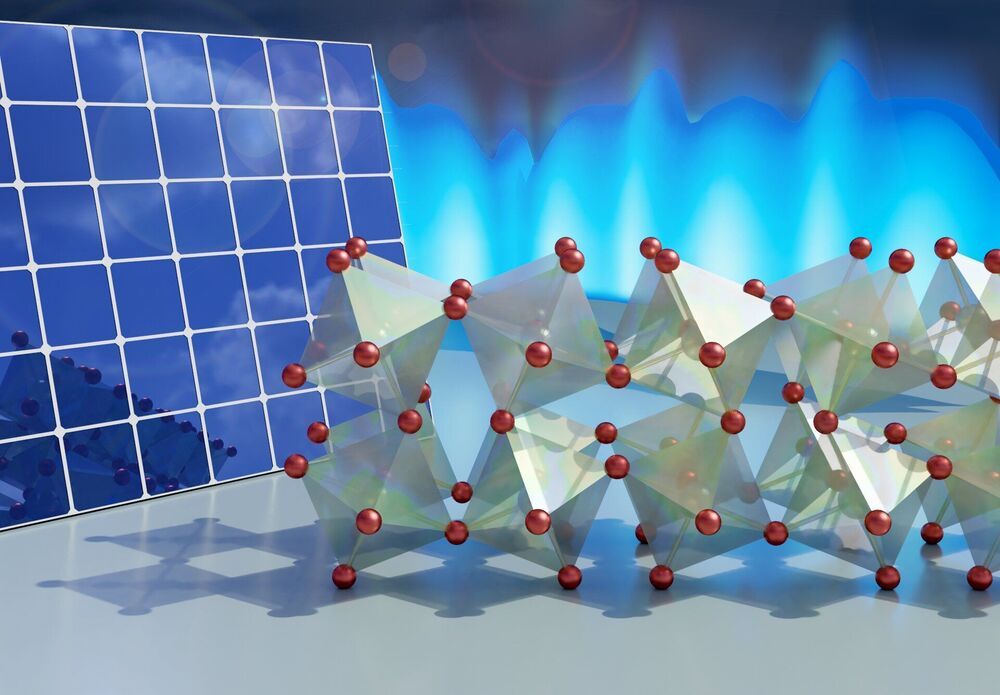

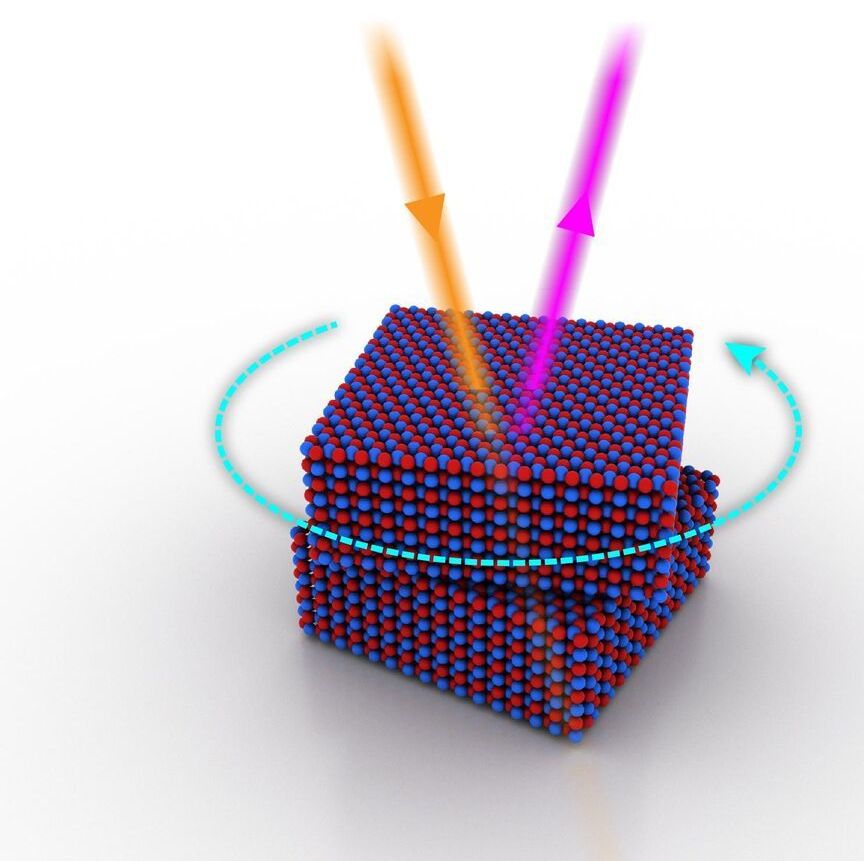

A new, simpler solution process for fabricating stable perovskite solar cells overcomes the key bottleneck to large-scale production and commercialization of this promising renewable-energy technology, which has remained tantalizingly out of reach for more than a decade.

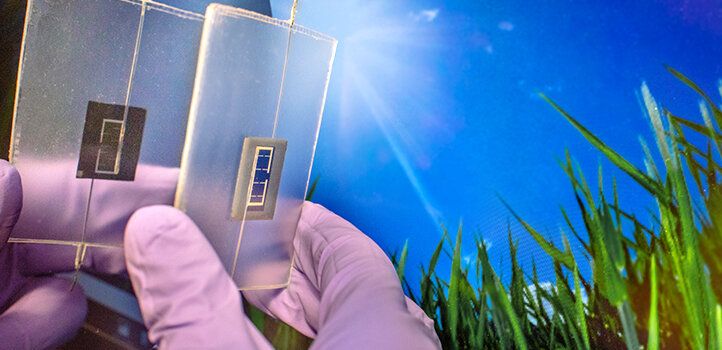

“Our work paves the way for low-cost, high-throughput commercial-scale production of large-scale solar modules in the near future,” said Wanyi Nie, a research scientist fellow in the Center of Integrated Nanotechnologies at Los Alamos National Laboratory and corresponding author of the paper, which was published today in the journal Joule. “We were able to demonstrate the approach through two mini-modules that reached champion levels of converting sunlight to power with greatly extended operational lifetimes. Since this process is facile and low cost, we believe it can be easily adapted to scalable fabrication in industrial settings.”

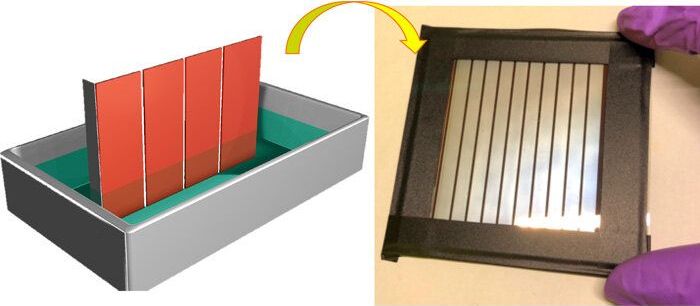

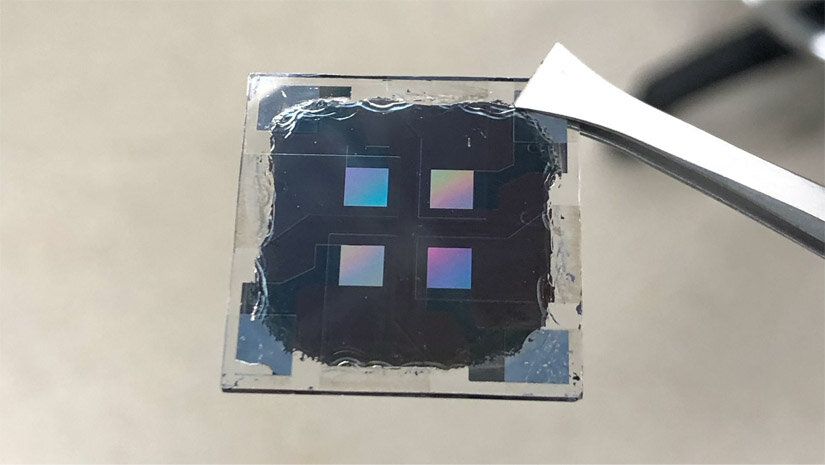

The team invented a one-step spin coating method using sulfolane, a liquid solvent. The new process allowed the team, a collaboration among Los Alamos and researchers from National Taiwan University (NTU), to produce high-yield, large-area photovoltaic devices that are highly efficient in creating power from sunlight. These perovskite solar cells also have a long operational lifetime.