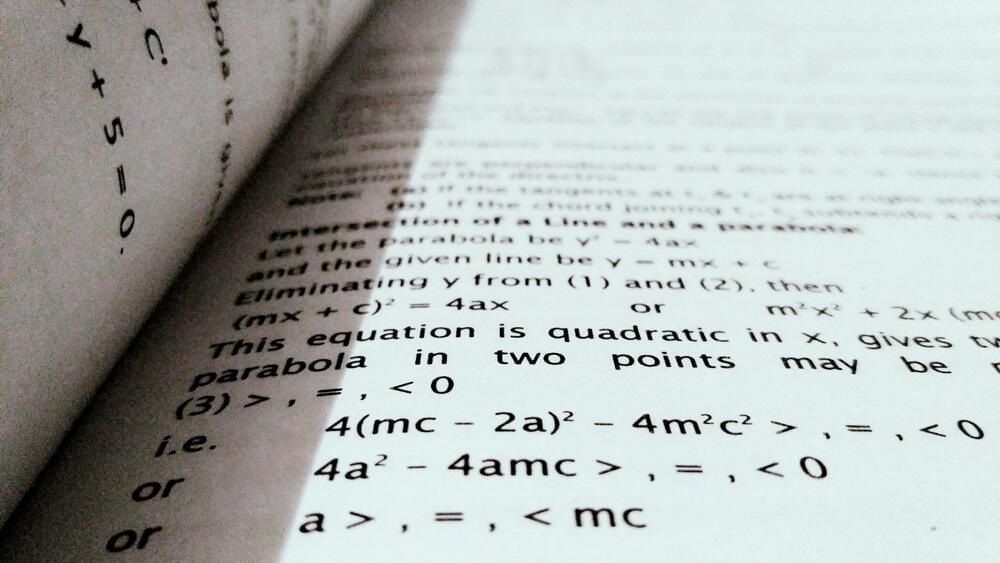

A small team of AI researchers at Microsoft reports that the company’s Orca-Math small language model outperforms other, larger models on standardized math tests. The group has published a paper on the arXiv preprint server describing their testing of Orca-Math on the Grade School Math 8K (GSM8K) benchmark and how it fared compared to well-known LLMs.

Many popular LLMs such as ChatGPT are known for their impressive conversational skills—less well known is that most of them can also solve math word problems. AI researchers have tested their abilities at such tasks by pitting them against the GSM8K, a dataset of 8,500 grade-school math word problems that require multistep reasoning to solve, along with their correct answers.

In this new study, the research team at Microsoft tested Orca-Math, an AI application developed by another team at Microsoft specifically designed to tackle math word problems, and compared the results with larger AI models.