Time may be a human construct but that hasn’t stopped physicists from perfecting it.

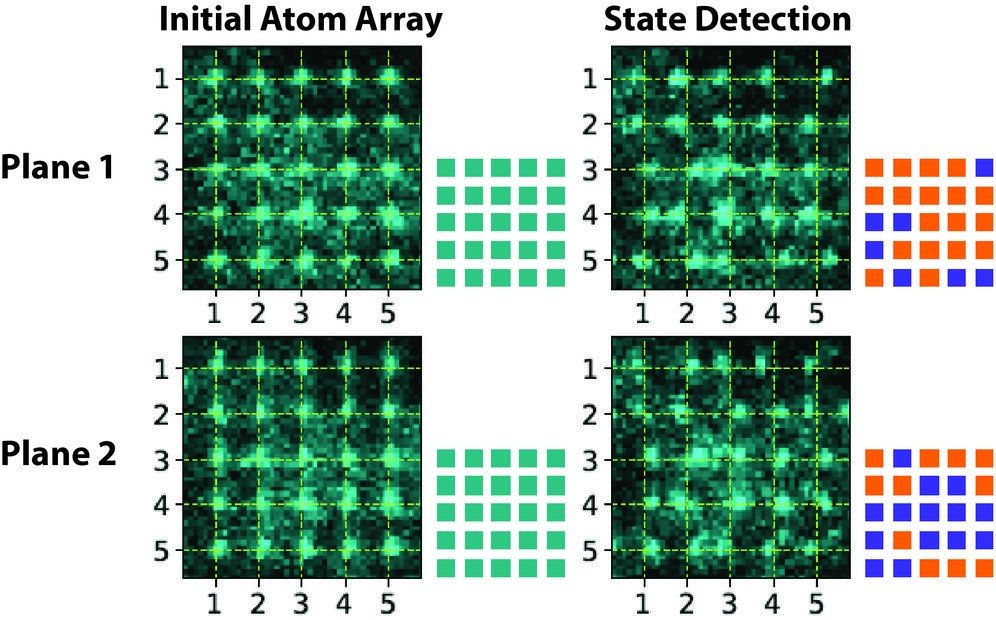

JILA’s 3D Quantum Gas Atomic Clock Offers New Dimensions in Measurement

https://www.nist.gov/news-events/news/2017/10/jilas-3-D-quan…easurement

“JILA physicists have created an entirely new design for an atomic clock, in which strontium atoms are packed into a tiny three-dimensional (3D) cube at 1,000 times the density of previous one-dimensional (1-D) clocks. In doing so, they are the first to harness the ultra-controlled behavior of a so-called “quantum gas” to make a practical measurement device.”

Jun Ye: Let There Be Light (and Thus, Time)

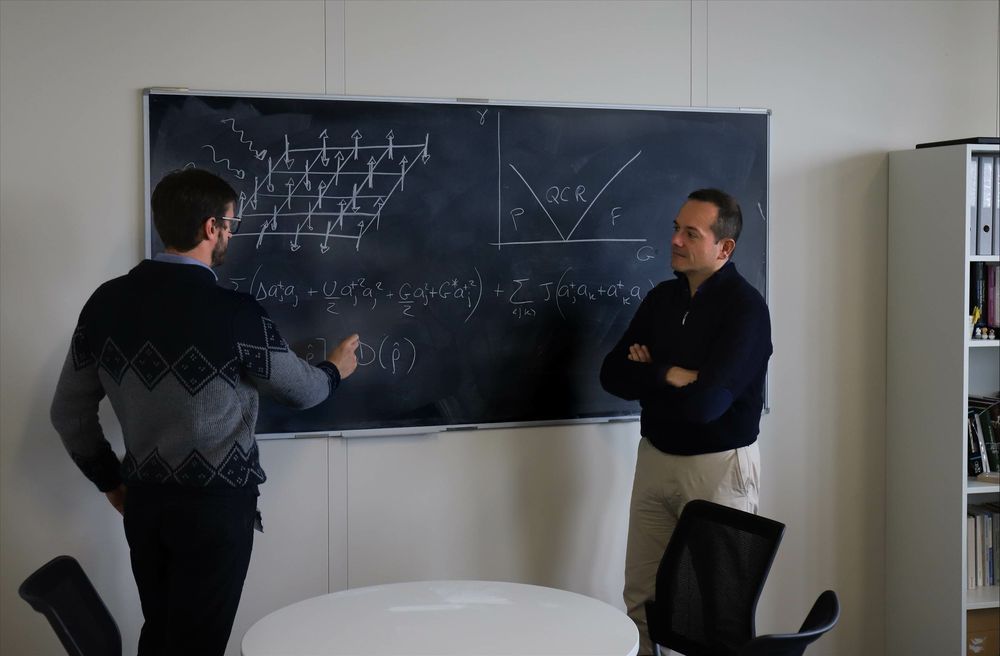

Dr. Jun Ye, professor of physics at the University of Colorado at Boulder and a fellow of both the National Institute of Standards and Technology and JILA, explains how lasers are used to manipulate atoms inside and out for ultra-precise clocks.

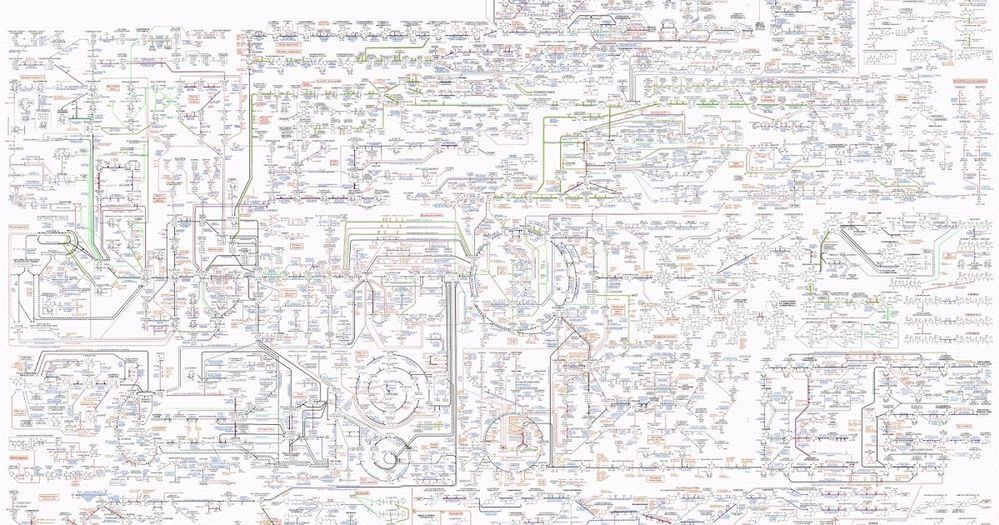

Ultra-Accurate Clocks Lead Search for New Laws of Physics.

Atomic clocks are letting physicists tighten the lasso around elusive phenomena such as dark matter.

Sign Up For The Seeker Newsletter Here — http://bit.ly/1UO1PxI

____________________