Twentieth Century technology has relied on the use of fuels and chemical propellants to propel our ships, planes, and cars. The propulsion technology of the future will not use chemical combustion to produce thrust, and the 21st century will see the emergence of propellant-less propulsion systems. Such technologies will provide the means to travel faster than ever before at a fraction of current costs and with no pollution by-products.

This becomes absolutely crucial for interplanetary and interstellar travel, as we have stated before in RSF commentary1 reporting on Resonance-based technology may provide inertial mass reduction—the future of space travel will not be performed with chemical propellants. As an example, to date the most viable proposal for an interstellar mission with current technological capabilities is the Breakthrough Starshot project which will use a fleet of light sail probes propelled to 20% percent the speed of light via laser pulses.

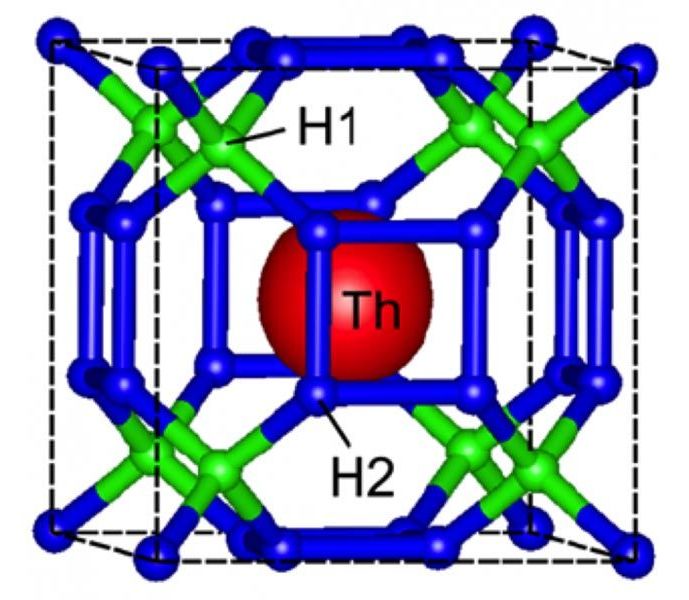

Considering the significant limitations of combustion-based propulsion (as well as the harmful environmental impacts), there is a strong drive to develop the next-generation propulsion systems that will move us into the next phase of technological advancement. Torus Tech, a research and development company founded by Nassim Haramein, the founder of the Resonance Science Foundation, is researching quantum vacuum engineering technologies that will enable gravitational control and zero-point energy production.