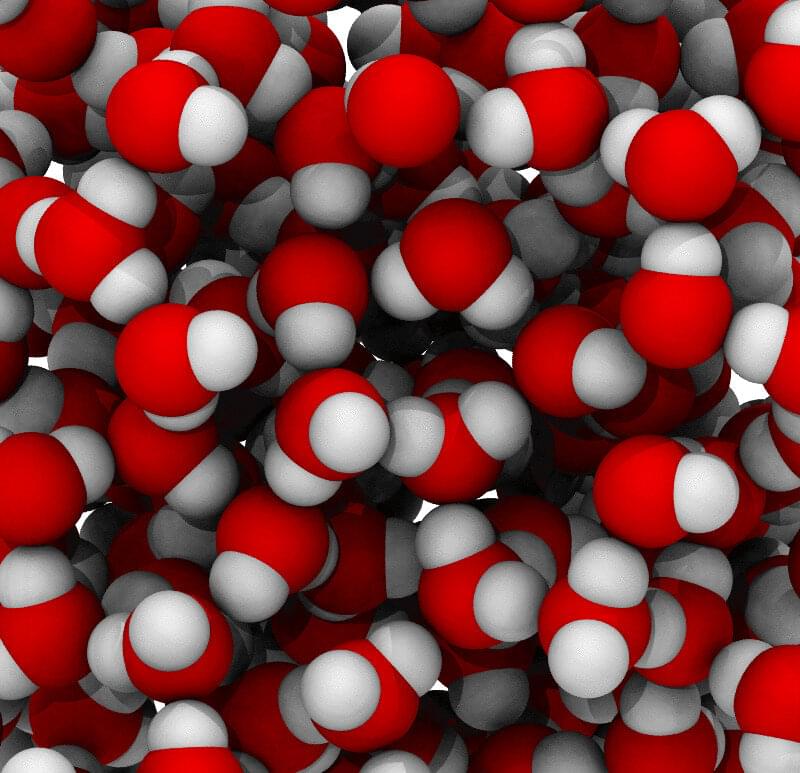

For decades, physicists have been hunting for a quantum-gravity model that would unify quantum physics, the laws that govern the very small, and gravity. One major obstacle has been the difficulty in testing the predictions of candidate models experimentally. But some of the models predict an effect that can be probed in the lab: a very small violation of a fundamental quantum tenet called the Pauli exclusion principle, which determines, for instance, how electrons are arranged in atoms.

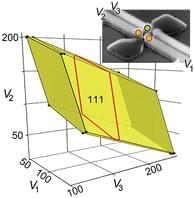

A project carried out at the INFN underground laboratories under the Gran Sasso mountains in Italy, has been searching for signs of radiation produced by such a violation in the form of atomic transitions forbidden by the Pauli exclusion principle.

In two papers appearing in the journals Physical Review Letters (published on September 19, 2022) and Physical Review D (accepted for publication on December 7, 2022) the team reports that no evidence of violation has been found, thus far, ruling out some quantum-gravity models.