Caltech research shows Barkhausen noise in magnets can also arise from quantum mechanics, not just classical methods.

The results, continuing the legacy of late Columbia professor Aron Pinczuk, are a step toward a better understanding of gravity.

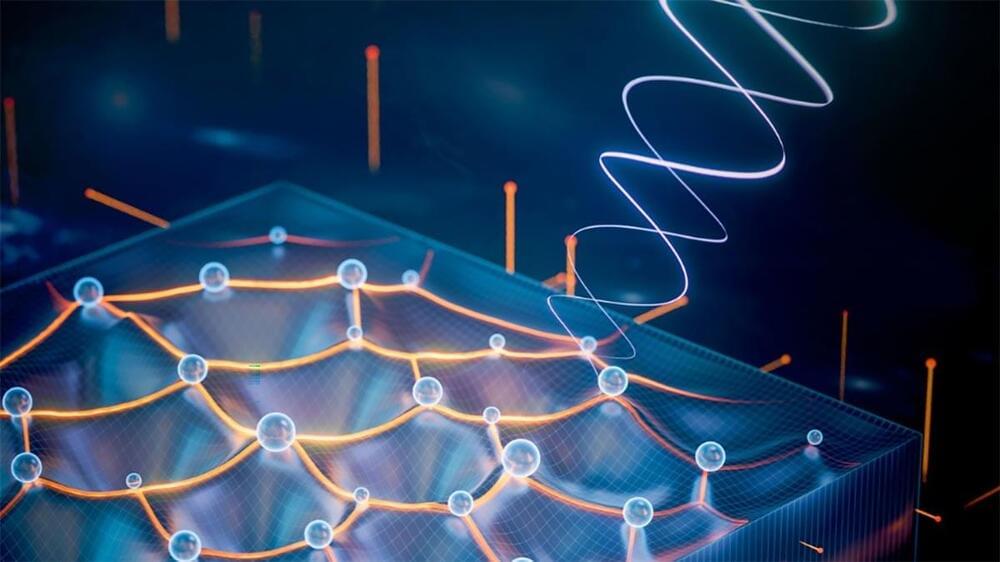

A team of scientists from Columbia, Nanjing University, Princeton, and the University of Munster, writing in the journal Nature, have presented the first experimental evidence of collective excitations with spin called chiral graviton modes (CGMs) in a semiconducting material.

A CGM appears to be similar to a graviton, a yet-to-be-discovered elementary particle better known in high-energy quantum physics for hypothetically giving rise to gravity, one of the fundamental forces in the universe, whose ultimate cause remains mysterious.

A new device consisting of a semiconductor ring produces pairs of entangled photons that could be used in a photonic quantum processor.

Quantum light sources produce entangled pairs of photons that can be used in quantum computing and cryptography. A new experiment has demonstrated a quantum light source made from the semiconductor gallium nitride. This material provides a versatile platform for device fabrication, having previously been used for on-chip lasers, detectors, and waveguides. Combined with these other optical components, the new quantum light source opens up the potential to construct a complex quantum circuit, such as a photonic quantum processor, on a single chip.

Quantum optics is a rapidly advancing field, with many experiments using photons to carry quantum information and perform quantum computations. However, for optical systems to compete with other quantum information technologies, quantum-optics devices will need to be shrunk from tabletop size to microchip size. An important step in this transformation is the development of quantum light generation on a semiconductor chip. Several research teams have managed this feat using materials such as gallium aluminum arsenide, indium phosphide, and silicon carbide. And yet a fully integrated photonic circuit will require a range of components in addition to quantum light sources.

A nanoresonator trapped in ultrahigh vacuum features an exceptionally high quality factor, showing promise for applications in force sensors and macroscopic tests of quantum mechanics.

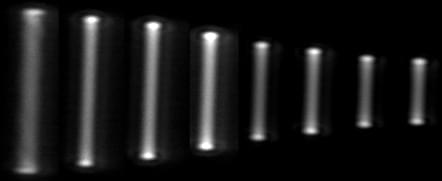

Nanomechanical oscillators could be used to build ultrasensitive sensors and to test macroscopic quantum phenomena. Key to these applications is a high quality factor (Q), a measure of how many oscillation cycles can be completed before the oscillator energy is dissipated. So far, clamped-membrane nanoresonators achieved a Q of about 1010, which was limited by interactions with the environment. Now a team led by Tracy Northup at the University of Innsbruck, Austria, reports a levitated oscillator—a floating particle oscillating in a trap—competitive with the best clamped ones [1]. The scheme offers potential for order-of-magnitude improvements, the researchers say.

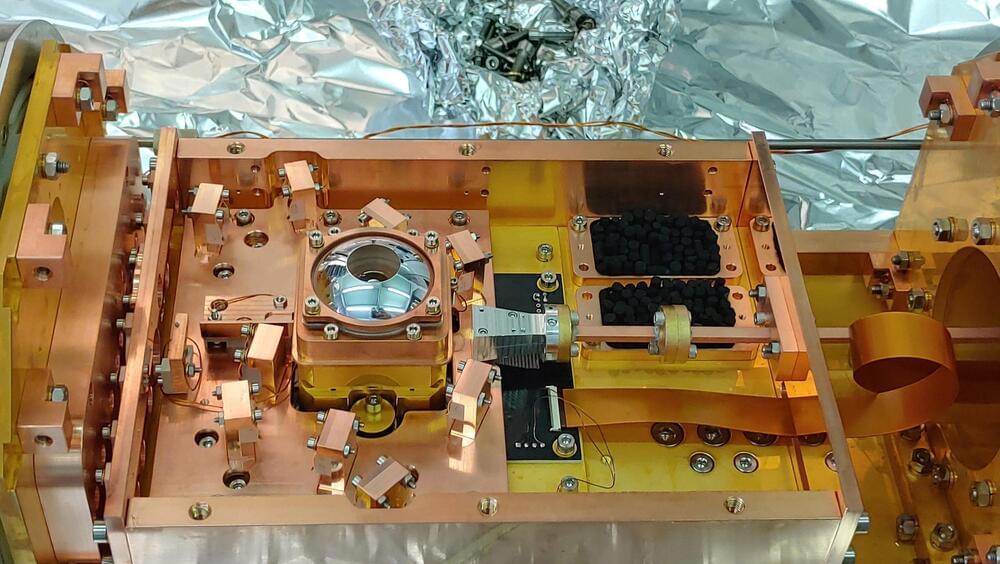

Theorists have long predicted that levitated oscillators, by eliminating clamping-related losses, could reach a Q as large as 1012. Until now, however, the best levitated schemes, based on optically trapped nanoparticles, achieved a Q of only 108. To further boost Q, the Innsbruck researchers devised a scheme that mitigated two important dissipation mechanisms. First, they replaced the optical trap with a Paul trap, one that confines a charged particle using time-varying electric fields instead of lasers. This approach eliminates the dissipation associated with light scattering from the trapped particle. Second, they trapped the particle in ultrahigh vacuum, where the nanoparticle collides with only about one gas molecule in each oscillation cycle.

Check out my course about quantum mechanics on Brilliant! First 30 days are free and 20% off the annual premium subscription when you use our link ➜ https://brilliant.org/sabine.

If you flip a light switch, the light will turn on. A cause and its effect. Simple enough… until quantum gravity come into play. Once you add quantum gravity, lights can turn on and make switches flip. And some physicists think that this could help build better computers. Why does quantum physics make causality so strange? And how can we use quantum gravity to build faster computers? Let’s have a look.

The paper on indefinite causal structures is here: https://arxiv.org/abs/quant-ph/0701019

🤓 Check out my new quiz app ➜ http://quizwithit.com/

💌 Support me on Donatebox ➜ https://donorbox.org/swtg.

📝 Transcripts and written news on Substack ➜ https://sciencewtg.substack.com/

👉 Transcript with links to references on Patreon ➜ / sabine.

📩 Free weekly science newsletter ➜ https://sabinehossenfelder.com/newsle…

👂 Audio only podcast ➜ https://open.spotify.com/show/0MkNfXl…

🔗 Join this channel to get access to perks ➜

/ @sabinehossenfelder.

🖼️ On instagram ➜ / sciencewtg.

#science #sciencenews #physics

Programming the Universe: A Quantum Computer Scientist Takes on the Cosmos. Seth Lloyd. xii + 221 pp. Alfred A. Knopf, 2006. $25.95.

In the 1940s, computer pioneer Konrad Zuse began to speculate that the universe might be nothing but a giant computer continually executing formal rules to compute its own evolution. He published the first paper on this radical idea in 1967, and since then it has provoked an ever-increasing response from popular culture (the film The Matrix, for example, owes a great deal to Zuse’s theories) and hard science alike.

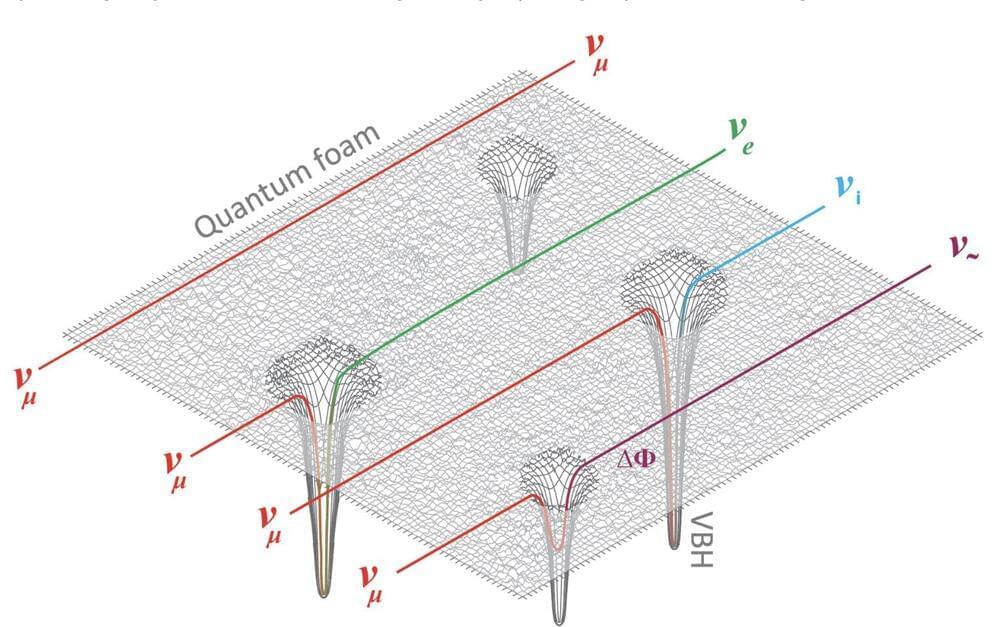

The manifestation of the quantum gravitational field becomes evident when observing phenomena at the Planck’s length scale. Hence, the tiniest constituent of our cosmos, which is not even perceptible, must exist at the scale of Planck’s length.