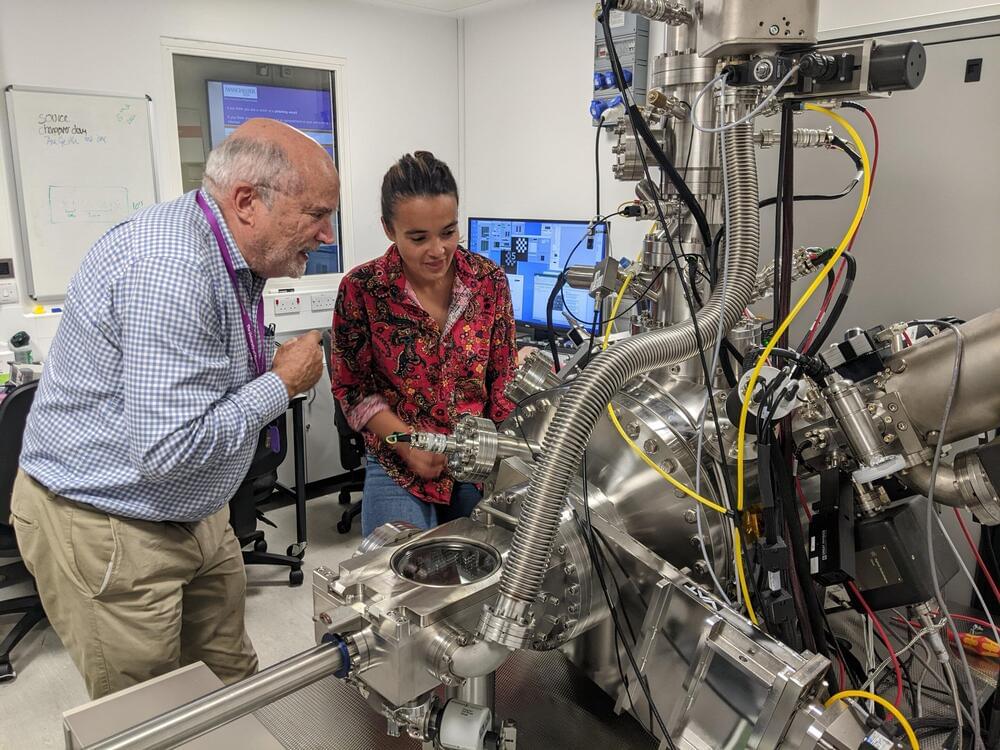

Researchers at AMOLF, working alongside colleagues from Germany, Switzerland, and Austria, have realized a new type of metamaterial through which sound waves flow in an unprecedented fashion. It provides a novel form of amplification of mechanical vibrations, which has the potential to improve sensor technology and information processing devices.

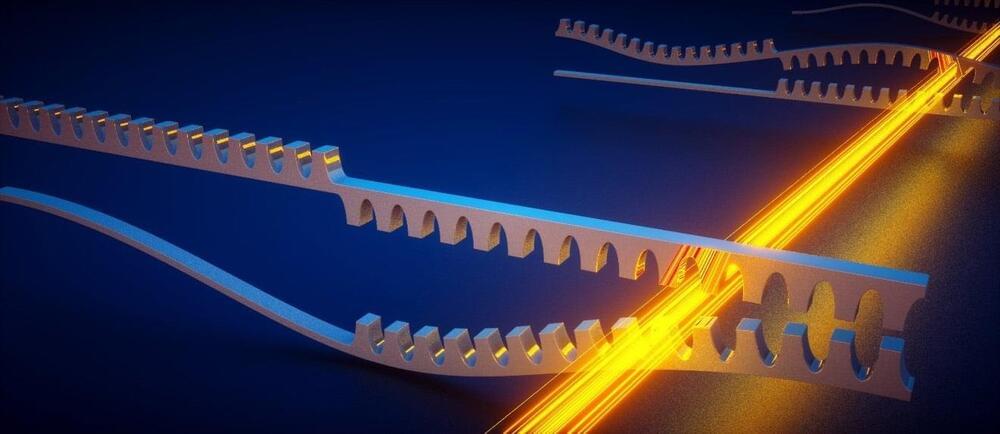

This metamaterial is the first instance of a so-called ‘bosonic Kitaev chain’, which gets its special properties from its nature as a topological material. It was realized by making nanomechanical resonators interact with laser light through radiation pressure forces. The discovery, which is published on March 27 in the renowned scientific journal Nature, was achieved in an international collaboration between AMOLF, the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Light, the University of Basel, ETH Zurich, and the University of Vienna.

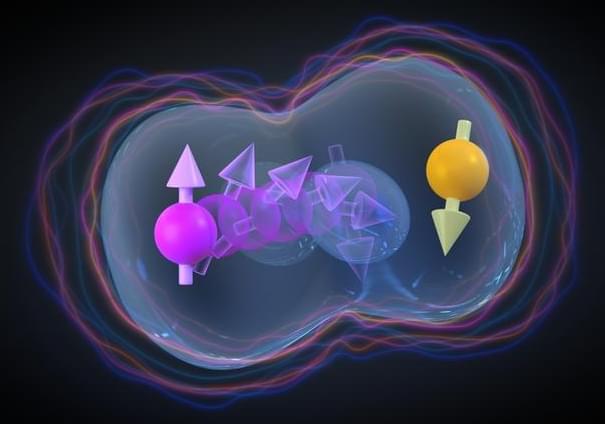

The ‘Kitaev chain’ is a theoretical model that describes the physics of electrons in a superconducting material, specifically a nanowire. The model is famous for predicting the existence of special excitations at the ends of such a nanowire: Majorana zero modes. These have gained intense interest because of their possible use in quantum computers.