Nvidia Corp., the chipmaker at the center of a boom in artificial intelligence use, is teaming up with Alphabet Inc.’s Google to pursue another technology once relegated to science fiction: quantum computing.

The initial product from this collaboration will be a 20-qubit system integrated with NVIDIA’s Grace Hopper Superchip, facilitating hybrid quantum-classical computing. This integration is expected to drive advancements in various fields, including financial services and artificial intelligence.

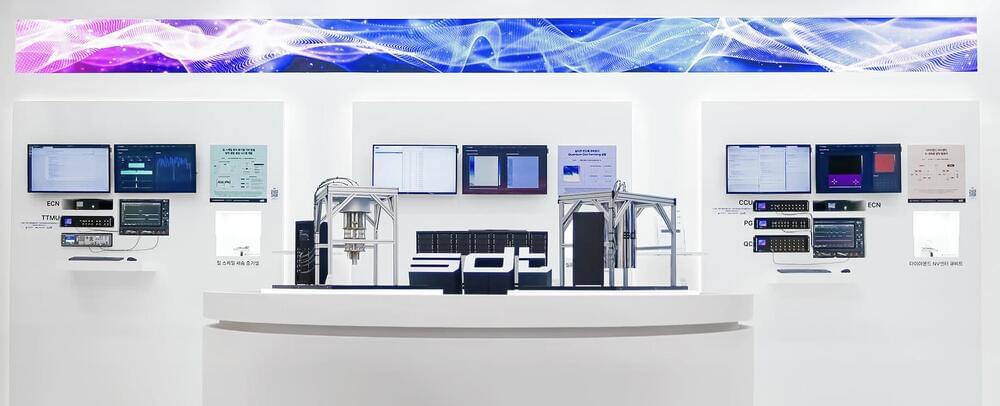

Through this joint venture, SDT and Anyon Technologies aim to establish a unique and robust partnership in the Asian quantum computing sector, leveraging their combined expertise to lead the commercialization and supply of superconducting quantum computers in the region.

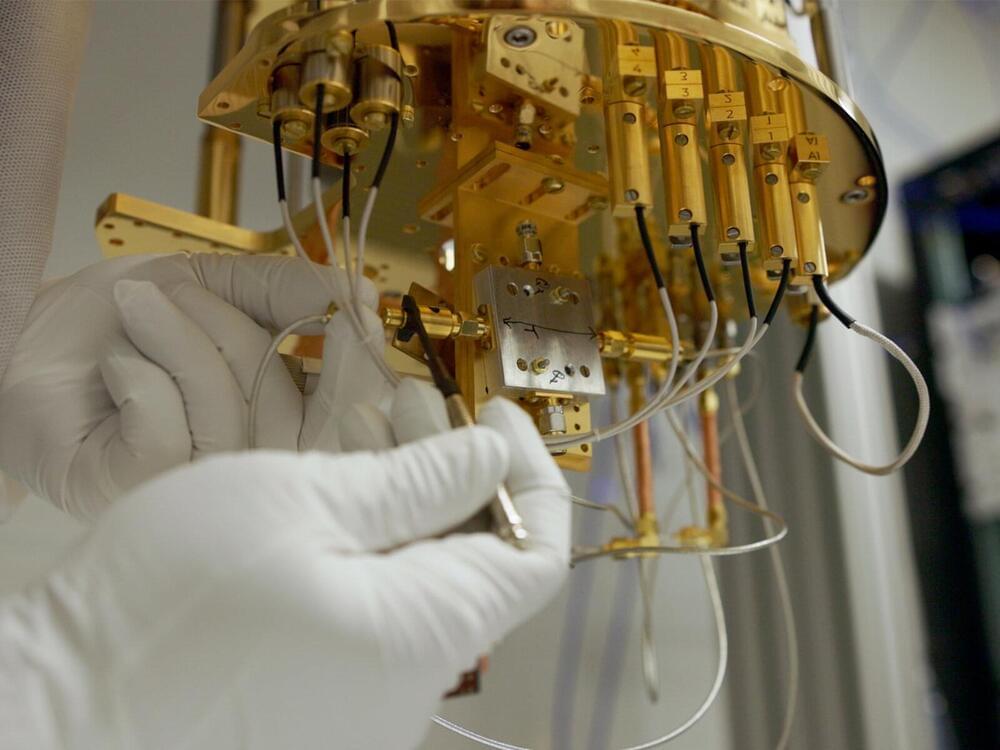

Now is the time to banish low-level radioactive energy sources from facilities that house and conduct experiments with superconducting qubits, according to a pair of recently published studies. Significantly improving quantum device coherence times is a key step toward an era of practical quantum computing.

Two complementary articles, published in the journal PRX Quantum and the Journal of Instrumentation, outline which sources of interfering ionizing radiation are most problematic for superconducting quantum computers and how to address them. The findings set the stage for quantitative study of errors caused by radiation effects in shielded underground facilities.

A research team led by physicists at the Department of Energy’s Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, in collaboration with colleagues at MIT’s Lincoln Laboratory, the National Institute of Standards and Technology, along with multiple academic partners, published their findings to assist the quantum computing community to prepare for the next generation of qubit development.

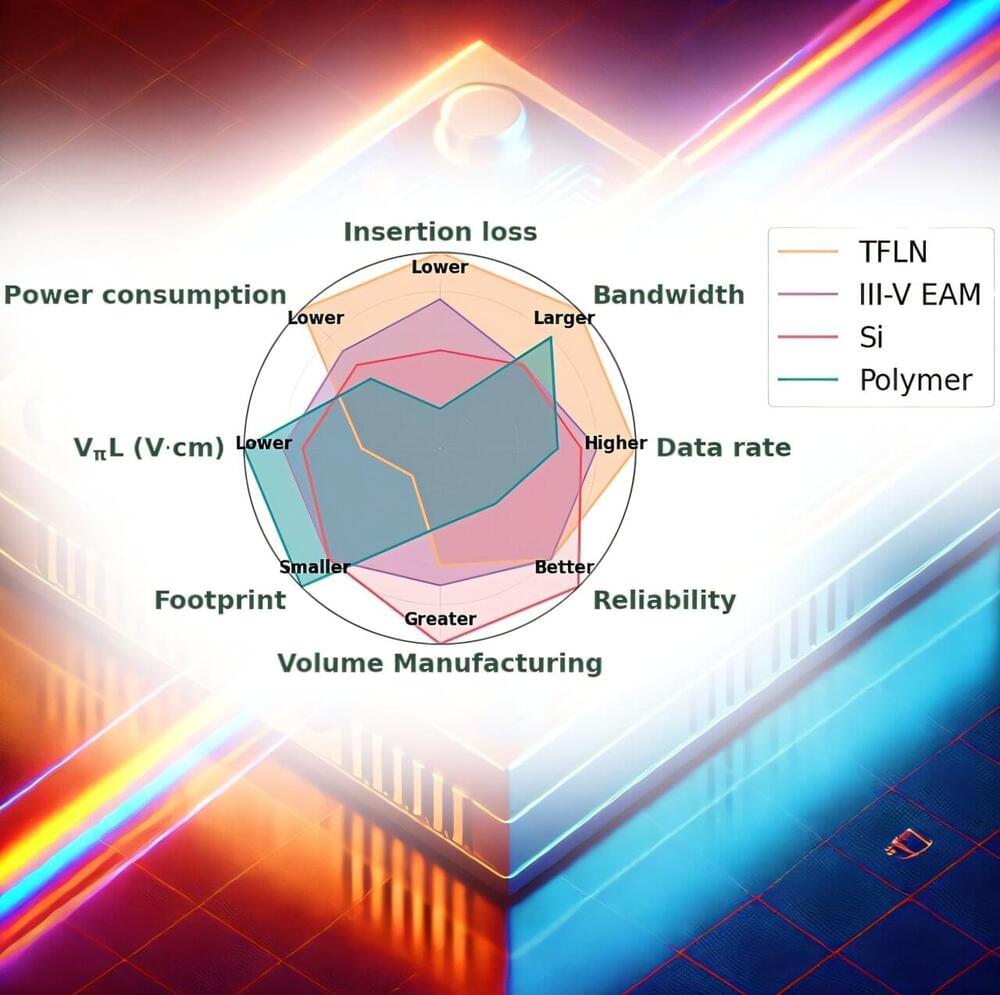

Despite being a mature technology in existence for over several decades, silicon photonic modulators face scrutiny from industry and academic experts. In a recent editorial interview, experts emphasize the need to explore alternatives beyond the traditional platforms. The discussion centers on innovative modulator materials and configurations that could cater to emerging applications in data centers, artificial intelligence, quantum information processing, and LIDAR. Experts also outline the challenges that lie ahead in this field.

Optical and photonic modulators are technologically advanced devices that enable the manipulation of light properties—such as power and phase—based on input signals. Over the decades, scientists have researched and developed silicon photonic modulators with wide-ranging applications, including optical data communication, sensing, biomedical technologies, automotive systems, astronomy, aerospace, and artificial intelligence (AI).

However, these modulators face bandwidth limitations and operational robustness issues stemming from the fundamental properties of silicon and other practical constraints, as highlighted by a panel of leading industry and academic experts in a recent editorial interview.

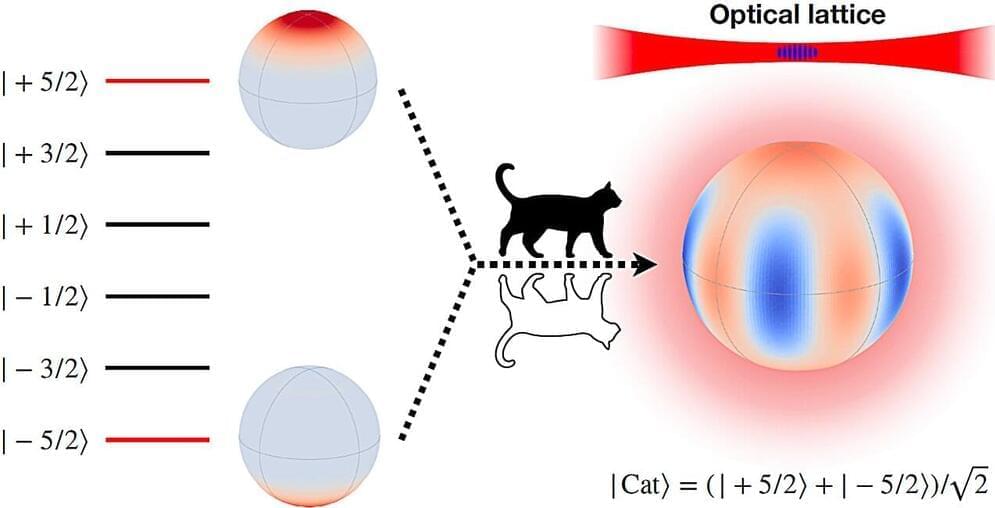

A team led by Prof. Lu Zhengtian and Researcher Xia Tian from the University of Science and Technology of China (USTC) realized a Schrödinger-cat state with minute-scale lifetime using optically trapped cold atoms, significantly enhancing the sensitivity of quantum metrology measurements. The study was published in Nature Photonics.

In quantum metrology, particle spin not only serves as a potent probe for measuring magnetic fields, inertia, and a variety of physical phenomena, but also holds the potential for exploring new physics beyond the Standard Model. The high-spin Schrödinger-cat state, a superposition of two oppositely directed and furthest-apart spin states, offers significant advantages for spin measurements.

On one hand, the high spin quantum number amplifies the precession frequency signal. On the other hand, the cat states are insensitive to some environmental interference, thus suppressing measurement noise. However, one major technical challenge in applying cat states in experiments is how to maintain a sufficiently long coherence time.

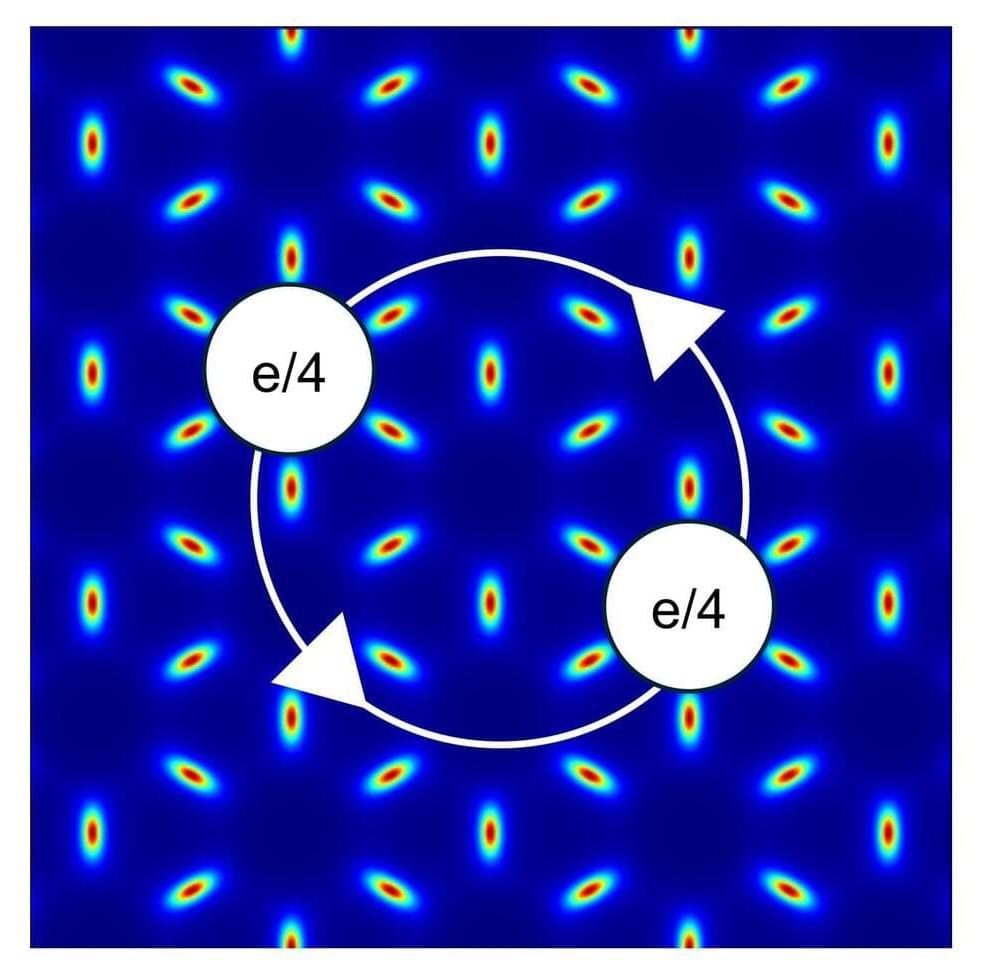

MIT physicists have shown that it should be possible to create an exotic form of matter that could be manipulated to form the qubit (quantum bit) building blocks of future quantum computers that are even more powerful than the quantum computers in development today.

The work builds on a discovery last year of materials that host electrons that can split into fractions of themselves but, importantly, can do so without the application of a magnetic field. The general phenomenon of electron fractionalization was first discovered in 1982 and resulted in a Nobel Prize.

That work, however, required the application of a magnetic field. The ability to create the fractionalized electrons without a magnetic field opens new possibilities for basic research and makes the materials hosting them more useful for applications.

In a groundbreaking experiment, scientists have achieved the remarkable feat of measuring the speed of quantum entanglement for the first time. This milestone in quantum physics research unveils new insights into one of nature’s most perplexing phenomena, opening doors to advanced quantum technologies and a deeper understanding of the universe’s fundamental workings.

Quantum computers have the potential to simulate complex materials, allowing researchers to gain deeper insights into the physical properties that emerge from interactions among atoms and electrons. This may one day lead to the discovery or design of better semiconductors, insulators, or superconductors that could be used to make ever faster, more powerful, and more energy-efficient electronics.

But some phenomena that occur in materials can be challenging to mimic using quantum computers, leaving gaps in the problems that scientists have explored with quantum hardware.

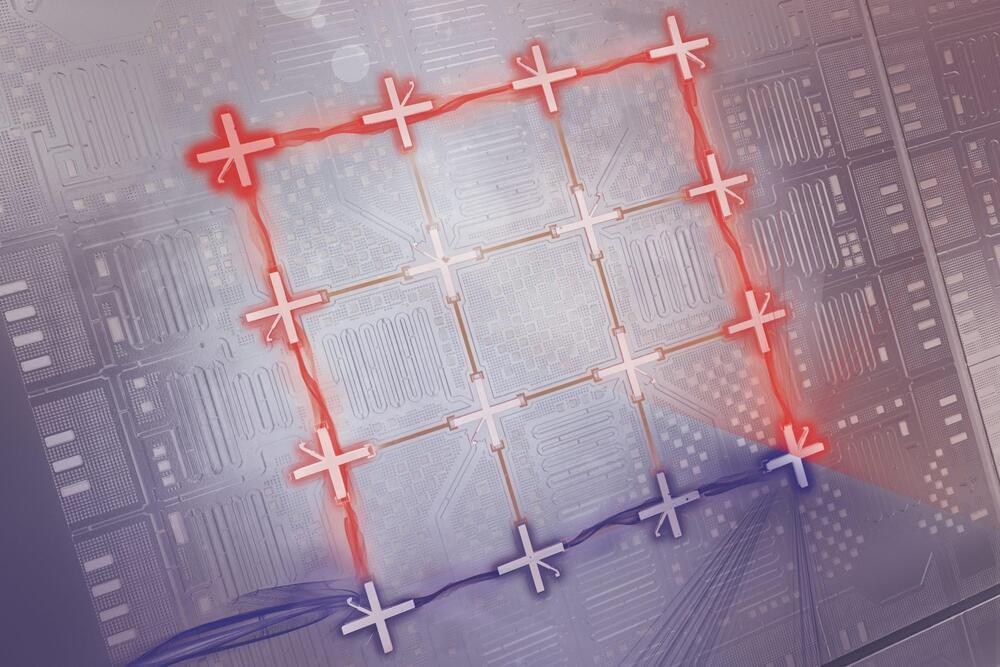

To fill one of these gaps, MIT researchers developed a technique to generate synthetic electromagnetic fields on superconducting quantum processors. The team demonstrated the technique on a processor comprising 16 qubits.

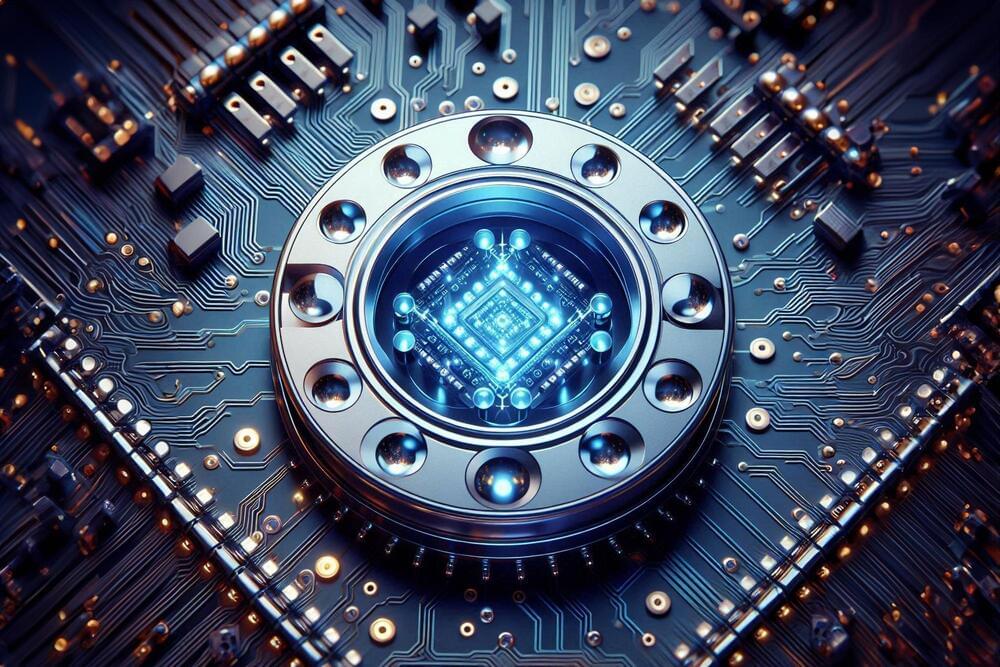

South Korean researchers have developed a groundbreaking photonic quantum circuit chip that promises to accelerate the global race in quantum computation.

This chip, capable of controlling up to eight photons, marks a significant leap forward in manipulating complex quantum phenomena like multipartite entanglement.

Breakthrough in photonic quantum circuit development.