Many quantum technologies function only at ultralow temperatures. Managing the flow of heat in these systems is crucial for protecting their sensitive components. Now Matteo Pioldi and his colleagues at the CNR Institute of Nanoscience and the Scuola Normale Superiore, both in Pisa, Italy, have devised a thermal analogue of a transistor that could facilitate this heat management [1]. Just as a transistor can control electric currents, the new device has the potential to control heat currents in cryogenic quantum systems.

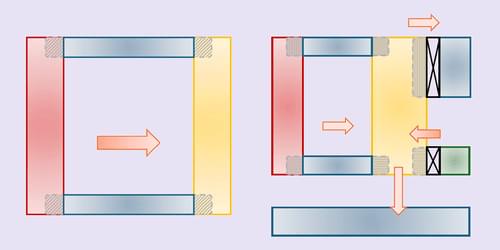

The most common type of transistor has three electrical terminals: the source, the gate, and the drain. Adjusting the voltage applied to the gate alters the strength of the electric current flowing from the source to the drain. In the proposed device, a semiconductor-based thermal reservoir serves as the source, and metallic thermal reservoirs serve as the gate and the drain. A second semiconductor-based reservoir exchanges heat with the source through photons and with the gate and the drain through electrons. Changing the gate’s temperature affects how easily heat flows through the device and, in turn, alters the strength of the heat current flowing from the source to the drain.

Pioldi and his colleagues performed numerical simulations of their device in a realistic setup at ultralow temperatures. They found that a small change in the strength of the heat current coming from the gate could cause the strength of the current between the source and the drain to increase by an amount that was 15 times larger. They say that their device could improve heat management in quantum circuits and thus help optimize quantum sensors, quantum computers, and other temperature-sensitive quantum systems.