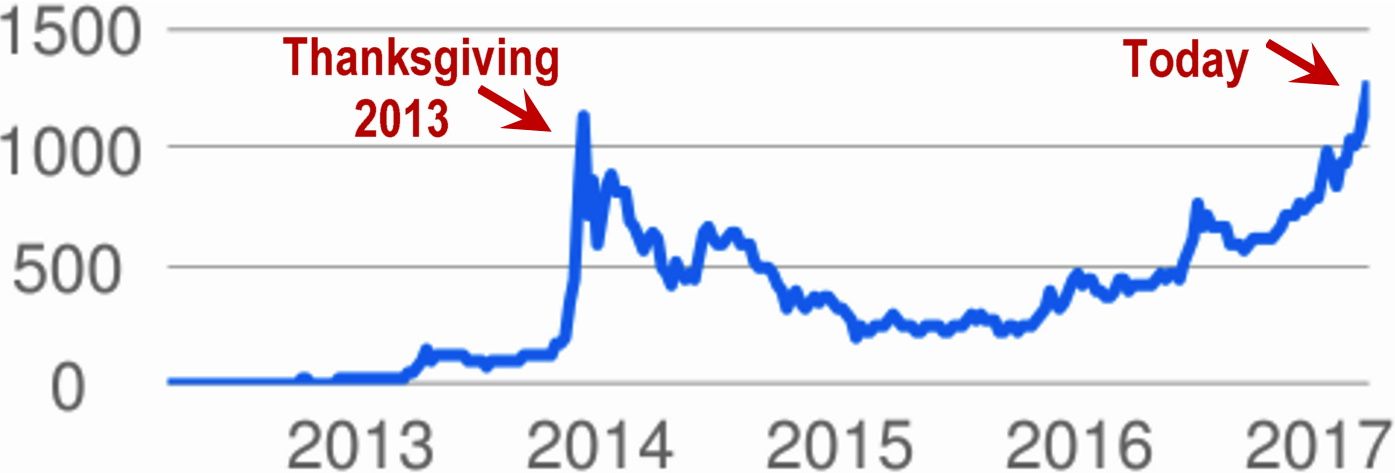

If you follow Bitcoin at all, then you know that its value is spiking. It has already surpassed a massive spike on Thanksgiving night 2013, and it has just surpassed the cost of an ounce of gold. [continue below image]

Like any commodity, the exchange value of Bitcoin is driven by supply and demand. But, unlike most commodities, including the US Dollar, the Euro or even gold, the eventual supply is capped. It is a mathematical certainty. Yet, demand is affected by many factors: Adoption as a payment instrument, early signs that it is being considered as a reserve currency, fascination by Geeks and early adopters and its use as a preferred tool by some criminals.

But chief among reasons for acquiring Bitcoin is speculation. Whether it is buy-and-hold or day trading, speculators still outnumber those who use Bitcoin to settle debts or to buy and sell other products and services. (Earlier this week, I argued that speculation is responsible for 85% of demand and of transactions—but that’s another story).

It’s a bit ironic that speculation—in the early days of a new market—retards organic adoption. It contributes to uncertainty and volatility, and it reduces the fraction available to the markets that make it both useful and liquid. Yet, in free markets, speculation is a necessary and critical antecedent to adoption.

This week, short term speculators have an unusually keen opportunity to profit, especially if they know how to buy a ‘put’ or sell a ‘call’ (i.e. to leverage a bet for or against the direction of Bitcoin, without actually acquiring any). For example, you can bet that an exchange-traded stock will fall, because there is a market for puts & calls. But it’s not as easy to bet against commodities that are not yet listed for options trading.

I am not going to give advice in this article. I am not a licensed investment professional and although I am bullish on long term, organic adoption of Bitcoin, I really don’t have an opinion on the current news or the short term prospects for a pull back. But, if you have an opinion on a current news event, then there is an immediate opportunity for you to make (or lose) a significantly leveraged sum in the next few days…

SEC and ETFs (Alphabet soup of investment banks)

Next weekend, on Saturday March 11, the United States Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) will approve or deny an application for the first regulated, recognized and significantly backed Bitcoin Exchange Traded Fund (ETF). Why is this significant? Because most investments are not hand picked by individual investors. Investors choose the level of risk or diversification that seems reasonable for their life stage and then leave stock-picking decisions to a formula, a market sector basket, or a fund manager. That is, invest or park their money in a fund rather than betting on Space-X, PayPal or the local electric company. [continue below image]

If approved, an ETF potentially adds massive new demand for a commodity, by offering a financial instrument than can be subscribed by the vast fraction of funds, investors, pensioners and speculators who prefer to leave asset management to an organization, outside broker or formula.

The first ETF application is created and backed by the Winkelvoss Twins. They were Olympic rowers, but found fame & fortune by contracting Marc Zuckerberg to create an early design for Facebook. If their application is approved, a dozen more investment banks, brokers and hedge funds are standing by to jump in with both feet.

This morning, Cointelegraph put the odds that the ETF will be approved at 50%. Some analysts place the chances even higher. But consider that Bitcoin has already spiked dramatically in the past few weeks. The excitement is already reflected in the price. So, where is the opportunity?

The opportunity, as with any speculative decision, is in the dissonance between your research and hunch compared with the overall market expectation reflected in the current price. So, for example, if Bitcoin is accepted as the basis for an ETF (and if it continues to grow in more fundamental adoption), the current price is actually remarkably low. Under these assumptions, it hasn’t even begun its period of rapid ascent. Perhaps more obviously (and even more short-term), if you believe that an ETF will be blocked by regulators, then the recent rise is likely to be reversed quickly, at least in the minutes after the March 11 decision is announced.

So how can you profit from your belief that a commodity will drop in value? I leave that to your personal investment knowledge and research or your financial advisor. My purpose is not to advise, nor even to teach about puts and calls. It is to point out that a few people will win or lose a lot of real money this coming weekend—at least on paper. And it all hinges on whether they can correctly predict the outcome of a regulatory decision process.

Again, Bitcoin is a very limited commodity, There are only 15.2 million coins today, and there will never be more than 21 million coins. This does not present an obstacle to adoption, because the coins can be sliced smaller and smaller as needed. In a noteworthy demonstration of ‘good deflation’, there will always be enough units for everyone—even if the entire world adopts it for every transaction under the sun.

Philip Raymond co-chairs Crypsa & Bitcoin Event, columnist & board member at Lifeboat, editor

at WildDuck and will deliver the keynote address at Digital Currency Summit in Johannesburg.