Please make sure your browser supports JavaScript and cookies and that you are not blocking them from loading. For more information you can review our Terms of Service and Cookie Policy.

The policy vacuum could impact refugees warns lawmaker.

The federal government in Australia has left it to the various departments to decide on the usage of artificial intelligence (AI) tools like ChatGPT instead of formulating a common policy for public services, ABC News.

Millions of users have experimented with tools like ChatGPT since it was introduced last year, and private organizations have jumped to make AI an integral part of their products and services to improve productivity and cut costs.

Biden’s energy policy is paying off big time.

SEOUL, May 26 (Reuters) — South Korea’s Hyundai Motor Group and LG Energy Solution Ltd (LGES) (373220.KS) on Friday said they will build a $4.3 billion electric vehicle (EV) battery plant in the United States amid a push to take advantage of tax credits.

Manufacturers must adhere to new U.S. sourcing requirements for EV battery components and critical minerals so that buyers of their vehicles can qualify for up to $7,500 in tax credits under the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA).

Vehicles from Hyundai Motor Co (005380.KS) and sister automaker Kia Corp (000270.KS) are currently not eligible.

Summary.

As businesses and governments race to make sense of the impacts of new, powerful AI systems, governments around the world are jostling to take the lead on regulation. Business leaders should be focused on who is likely to win this race, moreso than the questions of how or even when AI will be regulated. Whether Congress, the European Commission, China, or even U.S. states or courts take the lead will determine both the speed and trajectory of AI’s transformation of the global economy, potentially protecting some industries or limiting the ability of all companies to use the technology to interact directly with consumers.

Page-utils class= article-utils—vertical hide-for-print data-js-target= page-utils data-id= tag: blogs.harvardbusiness.org, 2007/03/31:999.357112 data-title= Who Is Going to Regulate AI? data-url=/2023/05/who-is-going-to-regulate-ai data-topic= Government policy and regulation data-authors= Blair Levin; Larry Downes data-content-type= Digital Article data-content-image=/resources/images/article_assets/2023/05/May23_28_5389503-383x215.jpg data-summary=

As the world reckons with the impact of powerful new AI systems, governments are jostling to lead the regulatory charge — and shape how this technology will grow.

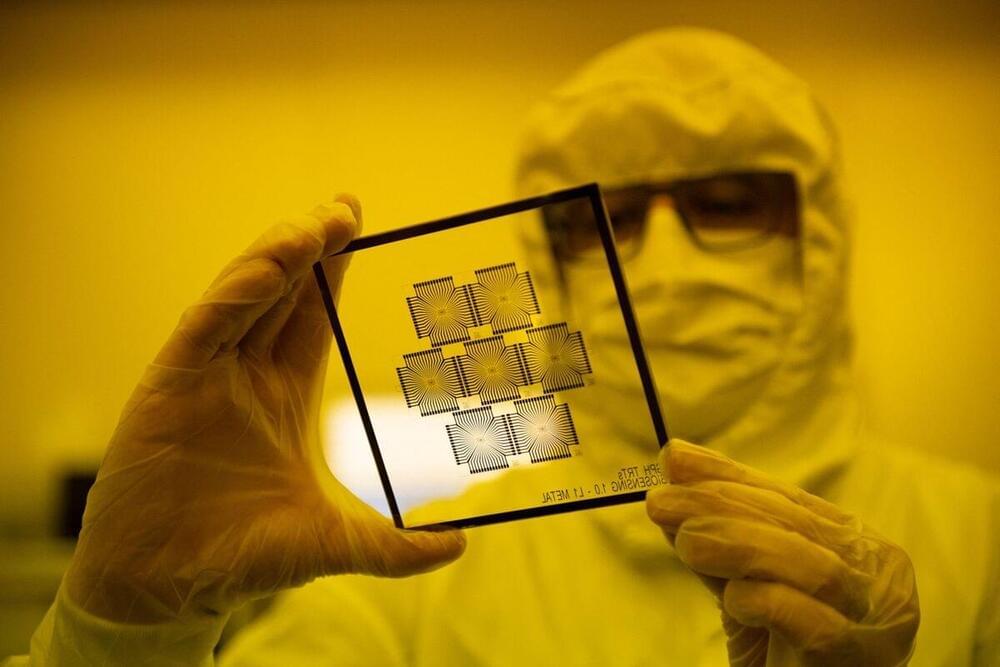

Researchers at the university of chicago.

Founded in 1,890, the University of Chicago (UChicago, U of C, or Chicago) is a private research university in Chicago, Illinois. Located on a 217-acre campus in Chicago’s Hyde Park neighborhood, near Lake Michigan, the school holds top-ten positions in various national and international rankings. UChicago is also well known for its professional schools: Pritzker School of Medicine, Booth School of Business, Law School, School of Social Service Administration, Harris School of Public Policy Studies, Divinity School and the Graham School of Continuing Liberal and Professional Studies, and Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering.

Our technological age is witnessing a breakthrough that has existential implications and risks. The innovative behemoth, ChatGPT, created by OpenAI, is ushering us inexorably into an AI economy where machines can spin human-like text, spark deep conversations and unleash unparalleled potential. However, this bold new frontier has its challenges. Security, privacy, data ownership and ethical considerations are complex issues that we must address, as they are no longer just hypothetical but a reality knocking at our door.

The G7, composed of the world’s seven most advanced economies, has recognized the urgency of addressing the impact of AI.

To understand how countries may approach AI, we need to examine a few critical aspects.

Clear regulations and guidelines for generative AI: To ensure the responsible and safe use of generative AI, it’s crucial to have a comprehensive regulatory framework that covers privacy, security and ethics. This framework will provide clear guidance for both developers and users of AI technology.

Public engagement: It’s important to involve different viewpoints in policy discussions about AI, as these decisions affect society as a whole. To achieve this, public consultations or conversations with the general public about generative AI can be helpful.