Scientists Create Matter from Pure Light, Demonstrating Einstein’s E=mc² Equation in Action.

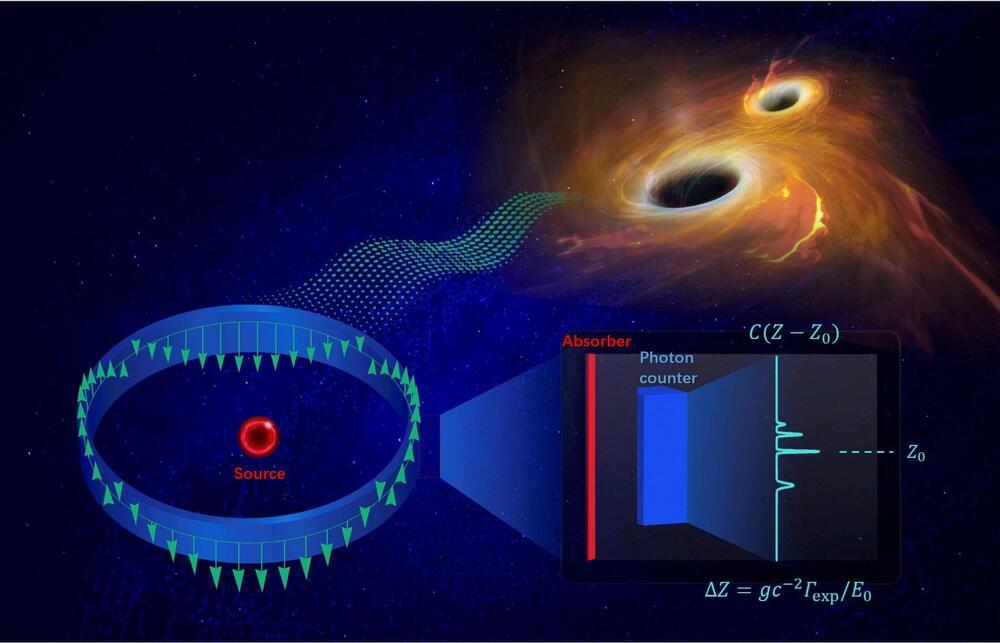

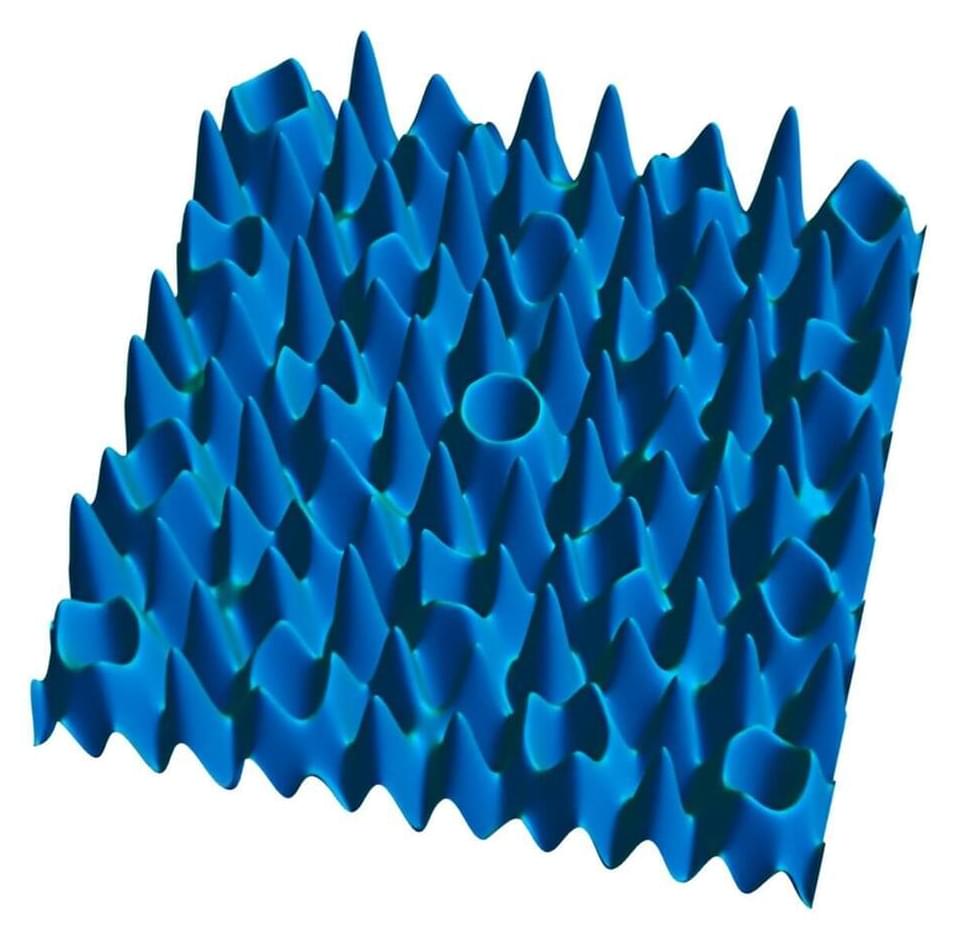

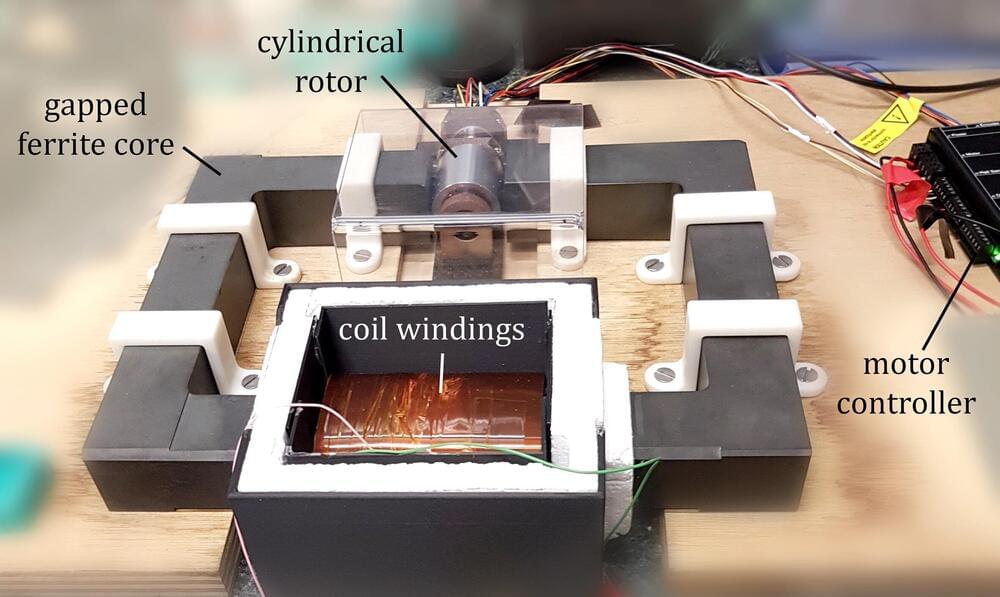

Physicists at Brookhaven National Laboratory have achieved a groundbreaking experiment, creating matter from light by demonstrating the Breit-Wheeler process. Using the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider, they accelerated heavy ions to generate nearly real photons, leading to the formation of electron-positron pairs. This experiment showcases Einstein’s E=mc² equation in action, aligning with predictions for transforming energy into matter. While these virtual photons act similarly to real ones, the experiment is a crucial step towards proving the process with real photons when technology advances to create gamma-ray lasers. Don’t forget to comment your thought about this!