He did groundbreaking work toward finding a “theory of everything.” He died in an Alpine rock-climbing accident.

This year’s other prizes include four in the life sciences, a special prize in fundamental physics for the invention of supergravity, one winner in mathematics, and a handful of $100,000 awards for early career researchers. Recipients will be honored at an awards gala to be held on November 3 at the NASA Ames Research Center in Mountain View, California, and broadcast live on National Geographic.

A record-setting black hole picture and advances in how we perceive pain are among the winners of this year’s $3-million prizes.

In the mid-1800’s to the early 1900’s Tesla file for more than 110 patents in varying technologies. From his magnifying transmitter, than uses an air coil or vortex to generate massive voltages, to wireless transmissions of power which Tesla used to prove transmission of data, power, and even lighting a layer of the strata as early as 1900. For this reason many consider Nikola Tesla to be one of the most brilliant scientists the world have ever seen.

Tesla’s dynamic theory of gravity explains the relation between gravity and electromagnetics in the same field. This was due to the presence of aether, also known as ether, which is a space-filling medium that is necessary for the propagation of forces either through electromagnetic or gravitational in nature. In plain English, Aether is the medium necessary for any exchange on these levels. Also, Aether was removed from theory in modern physics and was replaced with more abstract models. In looking at Tesla’s ideas and results; it appears that modern physics is wrong.

In the late 1800’s Tesla presented his Dynamic Theory of Gravity, which was a model over matter, Aether, and energy. Tesla’s version of this medium is closer to the gas theory and has extreme elasticity and a very high permeability. He also felt that Aether was much more common and filled all of the space.

“Dark energy is incredibly strange, but actually it makes sense to me that it went unnoticed,” said Noble Prize winning physicist Adam Riess in an interview. “I have absolutely no clue what dark energy is. Dark energy appears strong enough to push the entire universe – yet its source is unknown, its location is unknown and its physics are highly speculative.”

Physicists have found that for the last 7 billion years or so galactic expansion has been accelerating. This would be possible only if something is pushing the galaxies, adding energy to them. Scientists are calling this something “dark energy,” a force that is real but eludes detection.

One of the most speculative ideas for the mechanism of an accelerating cosmic expansion is called quintessence, a relative of the Higgs field that permeates the cosmos. Perhaps some clever life 5 billion years ago figured out how to activate that field, speculates astrophysicist Caleb Scharf in Nautil.us. How? “Beats me,” he says, “but it’s a thought-provoking idea, and it echoes some of the thinking of cosmologist Freeman Dyson’s famous 1979 paper ”Time Without End,” where he looked at life’s ability in the far, far future to act on an astrophysical scale in an open universe that need not evolve into a state of permanent quiescence. Where life and communication can continue for ever.

❤👍👍👍

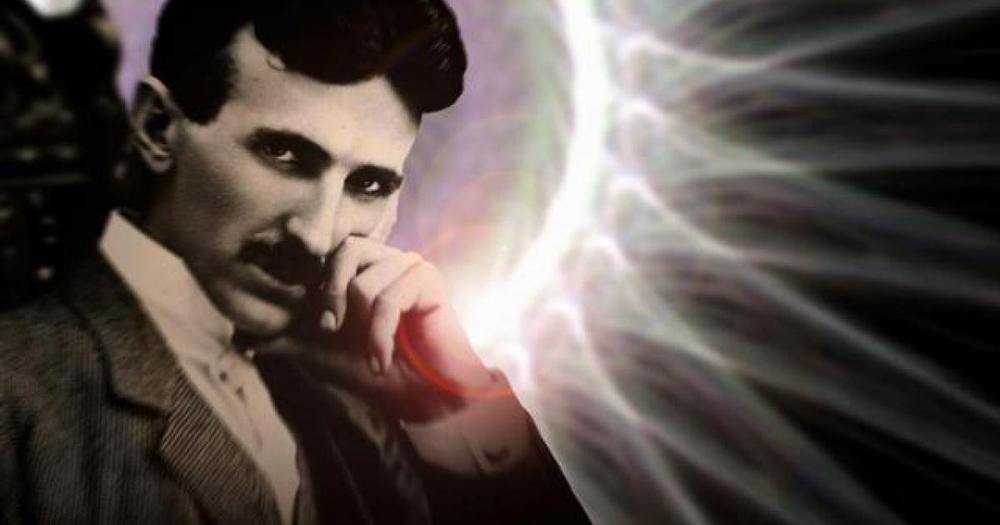

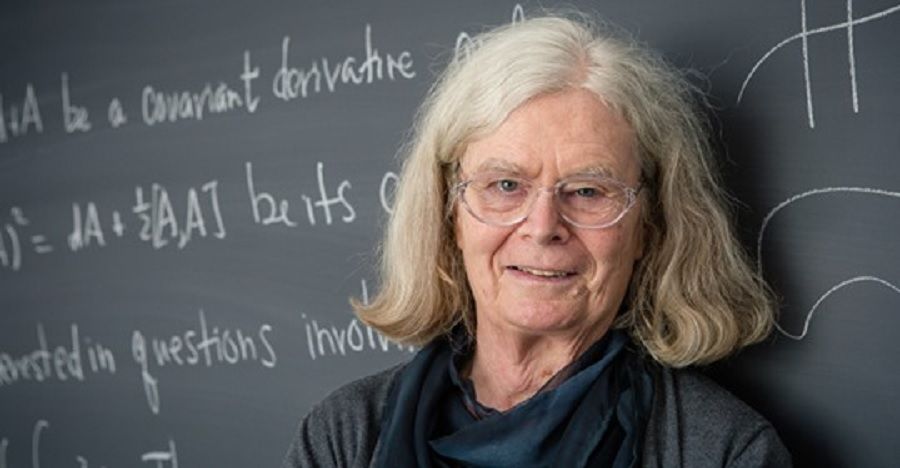

Greetings with some good news for the women’s world. Just recently, one of the most prestigious mathematics prizes in the world – The Abel Prize was awarded to a woman for the first time ever. Yes! Karen Uhlenbeck is a mathematician and a professor at the University of Texas and is now the first woman to win this prize in mathematics. You go Karen!

The award, which is modeled by the Nobel Prize, is awarded by the king of Norway to honor mathematicians who have made an influence in their field including a cash prize of around $700,000. The award to Karen cites for “the fundamental impact of her work on analysis, geometry and mathematical physics.” This award exists since 2003 but has only been won by men since.

Among her colleagues, Dr. Uhlenbeck is renowned for her work in geometric partial differential equations as well as integrable systems and gauge theory. One of her most famous contributions were her theories of predictive mathematics and in pioneering the field of geometric analysis.

PhD Project — Automating Scientific Discovery in Physics using Hybrid AI Models at University of Manchester, listed on FindAPhD.com.

Circa 2009

In just over a day, a powerful computer program accomplished a feat that took physicists centuries to complete: extrapolating the laws of motion from a pendulum’s swings.

Developed by Cornell researchers, the program deduced the natural laws without a shred of knowledge about physics or geometry.

The research is being heralded as a potential breakthrough for science in the Petabyte Age, where computers try to find regularities in massive datasets that are too big and complex for the human mind and its standard computational tools.

Dear Reader.

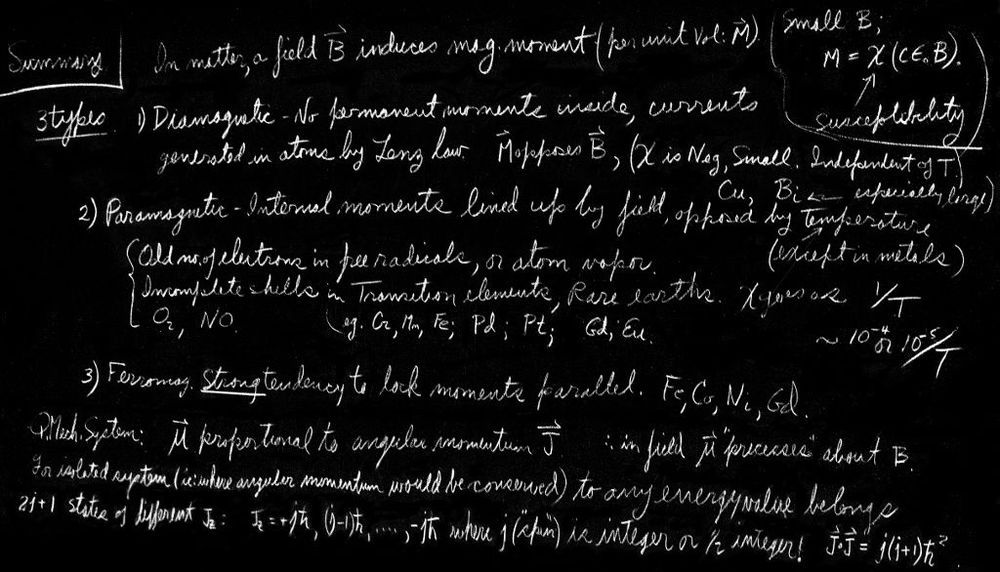

There are several reasons you might be seeing this page. In order to read the online edition of The Feynman Lectures on Physics, javascript must be supported by your browser and enabled. If you have have visited this website previously it’s possible you may have a mixture of incompatible files (.js,.css, and.html) in your browser cache. If you use an ad blocker it may be preventing our pages from downloading necessary resources. So, please try the following: make sure javascript is enabled, clear your browser cache (at least of files from feynmanlectures.caltech.edu), turn off your browser extensions, and open this page:

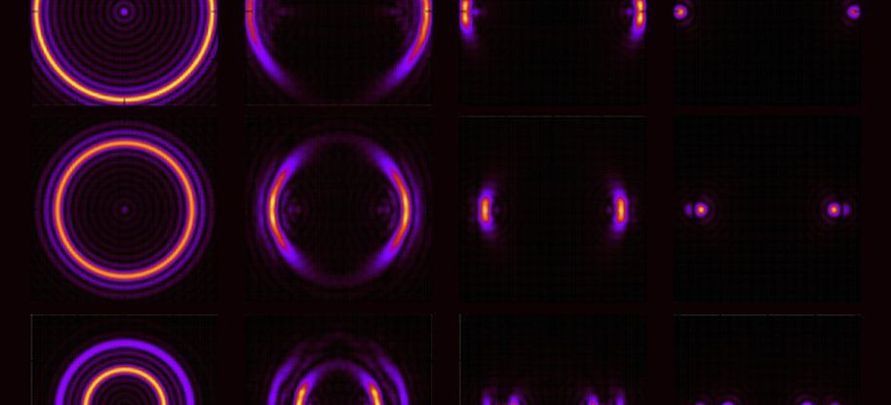

Black holes are some of the most powerful and fascinating phenomena in our Universe, but due to their tendency to swallow up anything nearby, getting up close to them for some detailed analysis isn’t possible right now.

Instead, scientists have put forward a proposal for how we might be able to model these massive, complex objects in the lab — using holograms.

While experiments haven’t yet been carried out, the researchers have put forward a theoretical framework for a black hole hologram that would allow us to test some of the more mysterious and elusive properties of black holes — specifically what happens to the laws of physics beyond its event horizon.