Physicists are exploring how life’s unique information-processing abilities might help us redefine what it means to be alive.

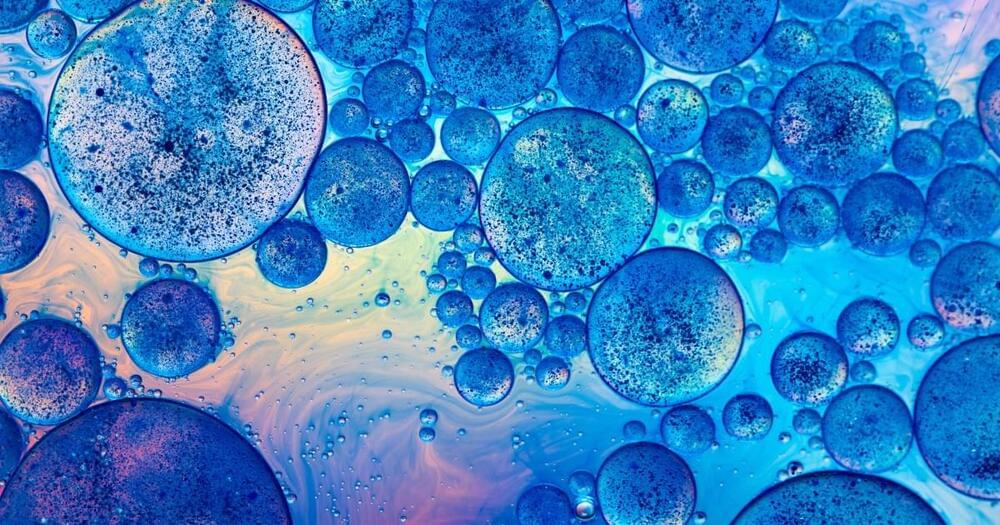

An international research group led by the Italian National Institute for Astrophysics (INAF) and comprising 34 research institutes and universities worldwide utilized the Near-Infrared Spectrograph (NIRSpec) on board the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) to witness the dramatic interaction between a quasar inside the PJ308–21 system and two massive satellite galaxies in the distant universe.

The observations, made in September 2022, unveiled unprecedented and awe-inspiring details, providing new insights into the growth of galaxies in the early universe. The results, presented July 5 during the European Astronomical Society (EAS 2024) meeting in Padua (Italy), will be published soon in Astronomy & Astrophysics.

Observations of this quasar (already described by the same authors in another study published last May), one of the first studied with NIRSpec when the universe was less than a billion years old (redshift z = 6.2342), have revealed data of sensational quality: the instrument “captured” the quasar’s spectrum with an uncertainty of less than 1% per pixel.

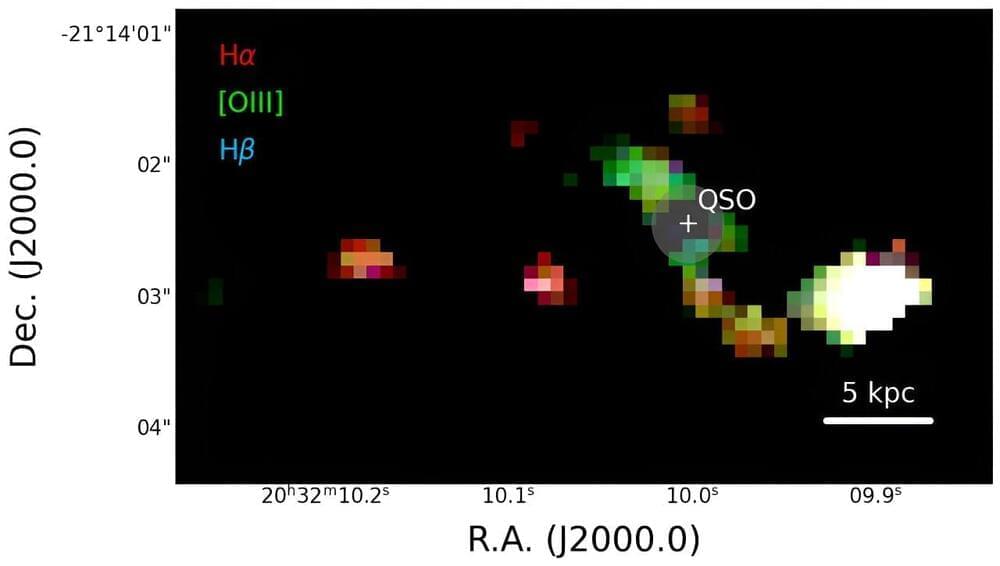

Researchers at Finland’s Aalto University have found a way to use magnets to line up bacteria as they swim. The approach offers more than just a way to nudge bacteria into order—it also provides a useful tool for a wide range of research, such as work on complex materials, phase transitions and condensed matter physics.

The paper is published in the journal Communications Physics.

Bacterial cells generally aren’t magnetic, so the magnets don’t directly interact with the bacteria. Instead, the bacteria are mixed into a liquid with millions of magnetic nanoparticles. This means the rod-shaped bacteria are effectively non-magnetic voids inside the magnetic fluid.

Speech recognition, weather forecasts, smart home applications: Artificial intelligence and the Internet of Things are enhancing our everyday lives. Systems based on reservoir computing are a very promising new field.

The research group led by Prof Dr. Karin Everschor-Sitte at the University of Duisburg-Essen (UDE), is conducting research in this area. They are primarily investigating new possibilities for reservoir computing, for example using magnetic materials.

Now, together with specialists from the field of ferroelectric materials, the team has shown that these systems are also suitable for processing complex data faster and more efficiently. Their results have been published in Nature Reviews Physics.

In an ongoing game of cosmic hide and seek, scientists have a new tool that may give them an edge. Physicists at the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory (PPPL) have developed a computer program incorporating machine learning that could help identify blobs of plasma in outer space known as plasmoids. In a novel twist, the program has been trained using simulated data.

The program will sift through reams of data gathered by spacecraft in the magnetosphere, the region of outer space strongly affected by Earth’s magnetic field, and flag telltale signs of the elusive blobs. Using this technique, scientists hope to learn more about the processes governing magnetic reconnection, a process that occurs in the magnetosphere and throughout the universe that can damage communications satellites and the electrical grid.

Scientists believe that machine learning could improve plasmoid-finding capability, aid the basic understanding of magnetic reconnection and allow researchers to better prepare for the aftermath of reconnection-caused disturbances.

As bristling with volcanoes as a porcupine with quills, Jupiter’s moon Io is the most volcanically active world in the Solar System. At any given time, around 150 of the 400 or so active volcanoes on Io are erupting. It’s constantly spewing out lava and gas; a veritable factory of volcanic excretions.

And, thanks to the Juno probe’s Jovian Infrared Auroral Mapper (JIRAM) imaging Jupiter and its surrounding environment, we now know a lot more about what a gloriously hot mess Io is.

“The high spatial resolution of JIRAM’s infrared images, combined with the favorable position of Juno during the flybys, revealed that the whole surface of Io is covered by lava lakes contained in caldera-like features,” says astrophysicist Alessandro Mura of the National Institute for Astrophysics in Italy.

Little more than a handful of corroded bronze wheels and heavily encrusted gears now remains of the ancient artifact called the Antikythera mechanism, leaving archaeologists to speculate over its functionality and purpose.

After decades of study, it’s largely agreed that the millennia-old device was something of an analog computer capable of keeping track of celestial movements. Yet with only fractured fragments to go by, researchers can only guess at the more intricate methods of its operation.

Researchers from the University of Glasgow in the UK have now used statistical modeling techniques borrowed from the study of gravitational waves to extrapolate missing details of a critical dial on Antikythera mechanism.

Shortform link: https://shortform.com/artemIn this video we will explore the concept of Hopfield networks – a foundational model of associative memory that u…

Patreon: https://bit.ly/3v8OhY7Sean Carroll is Homewood Professor of Natural Philosophy at Johns Hopkins University and fractal faculty at the Santa Fe Insti…

Dr. Georg Northoff is a neuroscientist, psychiatrist, and philosopher holding doctorates in all three disciplines. In this episode, we begin by discussing the self, and consciousness. We then enter into a dialogue about what he terms the world-brain problem, in contrast to the mind-body problem. He shares what he means by the neuroecological approach, why space and time are central to understanding the mind, and how it has foundational implications to diagnosis, treatment and research. We then talk about the practical implications of his viewpoint, for laymen and professionals alike. We follow by pivoting to cover topics such as the importance of philosophy in science, his stance on free will, and a series of rapid fire bonus questions that you don’t want to miss out on. We end on a review of his journey into becoming an MD, Ph.D, his future projects and words of wisdom for anyone listening. I invite you to skip around if you find any of these topics of particular interest to you.

Website: drchancnc.com.

Instagram: @draldrichan.

Guest website: http://www.georgnorthoff.com/

Books:

Reassembling Models of Reality: https://a.co/d/9s6Qu2J

The Spontaneous Brain: https://a.co/d/ewKjT0Y