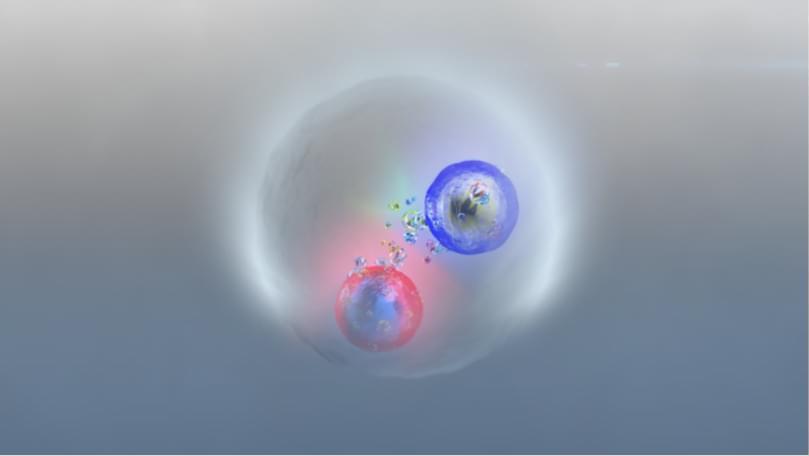

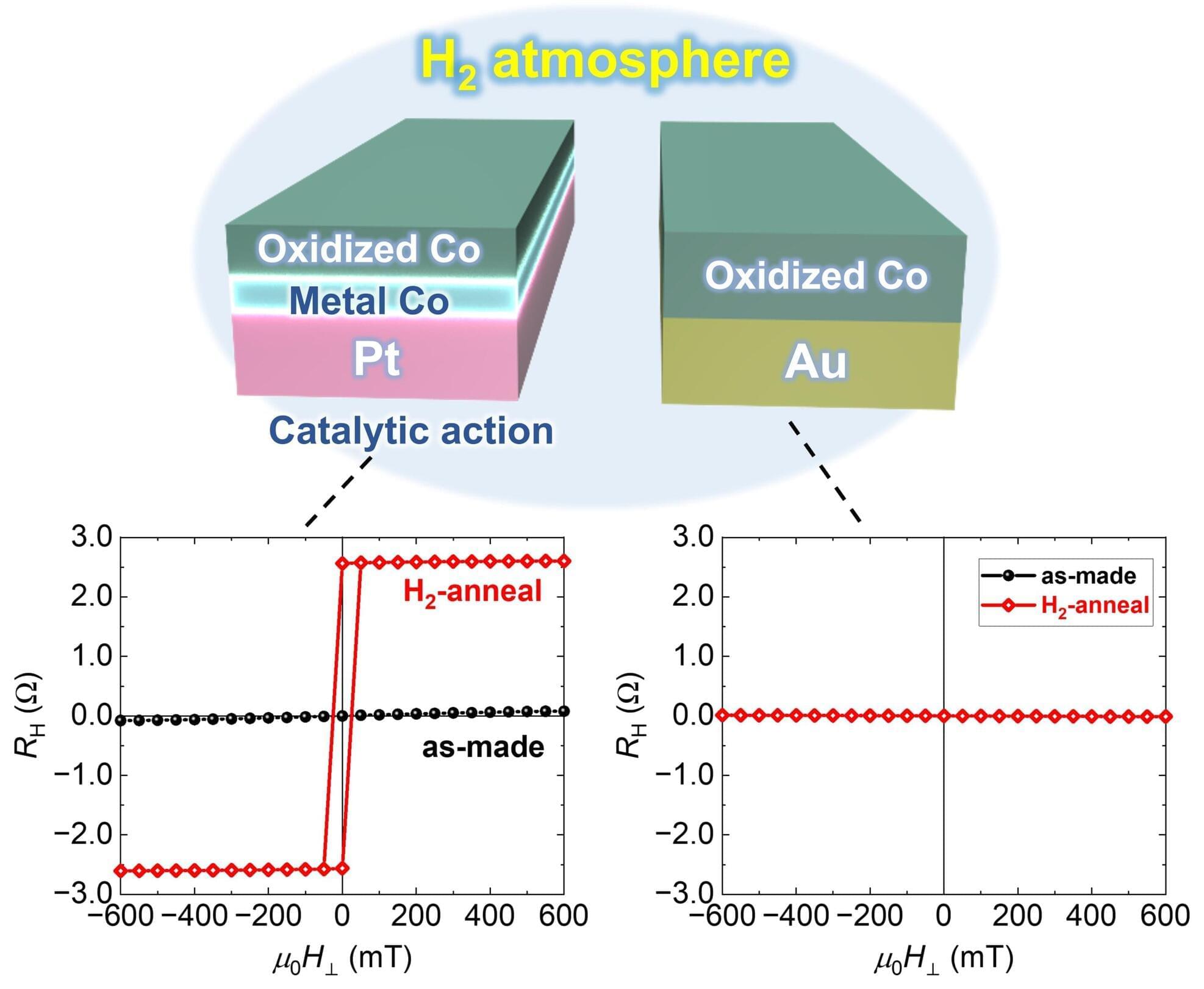

An unforeseen feature in proton-proton collisions previously observed by the CMS experiment at CERN’s Large Hadron Collider (LHC) has now been confirmed by its sister experiment ATLAS. The result, reported yesterday at the European Physical Society’s High-Energy Physics conference in Marseille, suggests that top quarks – the heaviest and shortest-lived of all the elementary particles – can momentarily pair up with their antimatter counterparts to produce a “quasi-bound-state” called toponium. Further input based on complex theoretical calculations of the strong nuclear force — called quantum chromodynamics (QCD) — will enable physicists to understand the true nature of this elusive dance.

High-energy collisions between protons at the LHC routinely produce top quark–antiquark pairs. Measuring the probability, or cross section, of this process is both an important test of the Standard Model of particle physics and a powerful way to search for the existence of new particles that are not described by the theory.

Last year, CMS researchers were analysing a large sample of top quark–antiquark production data collected from 2016 to 2018 to search for new types of Higgs bosons when they observed something unusual. The team saw a surplus of top quark–antiquark pairs, which is often considered as a smoking gun for the presence of new particles. Intriguingly, the excess appeared at the very minimum energy required to produce such a pair of top quarks. This led the team to consider an alternative hypothesis of something that had long been considered too difficult to detect at the LHC: a short-lived union of a top quark and a top antiquark.