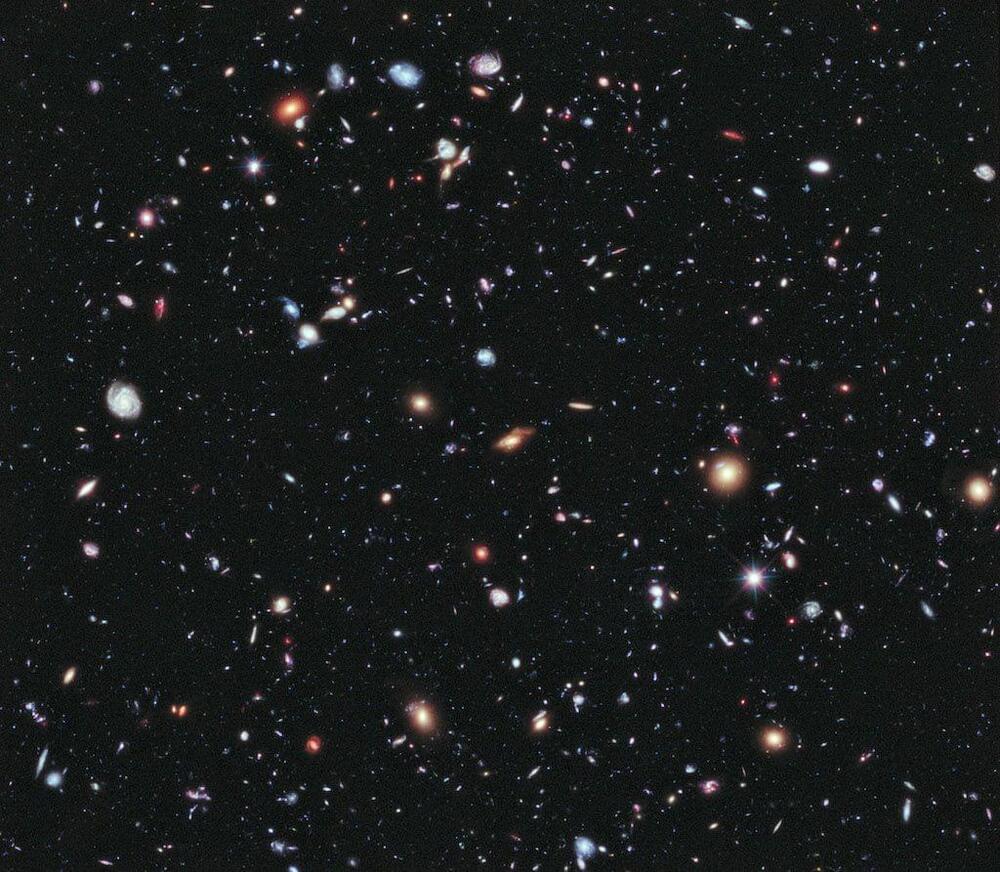

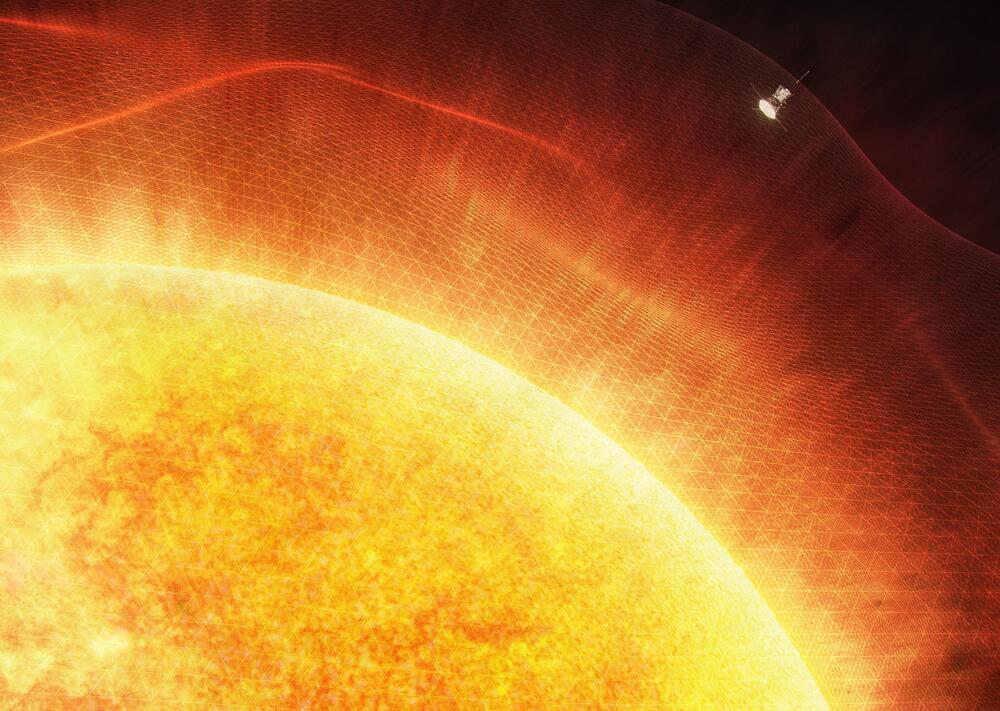

The nature of dark matter continues to perplex astronomers. As the search for dark matter particles continues to turn up nothing, it’s tempting to throw out the dark matter model altogether, but indirect evidence for the stuff continues to be strong. So what is it? One team has an idea, and they’ve published the results of their first search.

The conditions of dark matter mean that it can’t be regular matter. Regular matter (atoms, molecules, and the like) easily absorbs and emits light. Even if dark matter were clouds of molecules so cold they emitted almost no light, they would still be visible by the light they absorb. They would appear like dark nebulae commonly seen near the galactic plane. But there aren’t nearly enough of them to account for the effects of dark matter we observe. We’ve also ruled out neutrinos. They don’t interact strongly with light, but neutrinos are a form of “hot” dark matter since neutrinos move at nearly the speed of light. We know that most dark matter must be sluggish, and therefore “cold.” So if dark matter is out there, it must be something else.

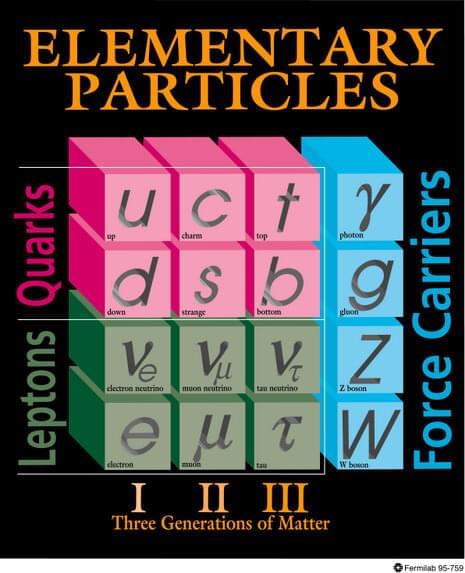

In this latest work, the authors argue that dark matter could be made of particles known as scalar bosons. All known matter can be placed in two large categories known as fermions and bosons. Which category a particle is in depends on a quantum property known as spin. Fermions such as electrons and quarks have fractional spin such as 1/2 or 3/2. Bosons such as photons have an integer spin such as 1 or 0. Any particle with a spin of 0 is a scalar boson.