Watch the full documentary on TUBI (free w/ads):

https://tubitv.com/movies/613341/consciousness-evolution-of-the-mind.

IMDb-accredited film, rated TV-PG

Director: Alex Vikoulov.

Narrator: Forrest Hansen.

Copyright © 2021 Ecstadelic Media Group, Burlingame, California, USA

*Based on The Cybernetic Theory of Mind eBook series (2022) by evolutionary cyberneticist Alex M. Vikoulov, available on Amazon:

as well as his magnum opus The Syntellect Hypothesis: Five Paradigms of the Mind’s Evolution (2020), available as eBook, paperback, hardcover, and audiobook on Amazon:

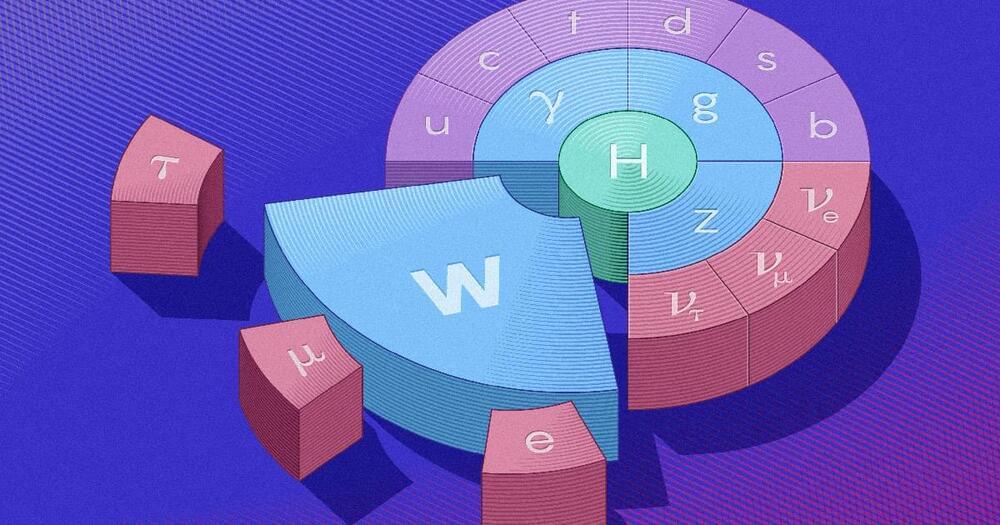

“You can’t explain consciousness in terms of classical physics or neuroscience alone. The best description of reality should be monistic. Quantum physics and consciousness are thus somehow linked by a certain mechanism… It is consciousness that assigns measurement values to entangled quantum states (qubits-to-digits of qualia, if you will). If we assume consciousness is fundamental, most phenomena become much easier to explain.

The Mind-Body dilemma has been known ever since René Descartes as Cartesian Dualism and later has been reformulated by the Australian philosopher David Chalmers as the ‘hard problem’ of consciousness. Western science and philosophy have been trying for centuries now, rather unsuccessfully, to explain how mind emerges from matter while Eastern philosophy dismisses the hard problem of consciousness altogether by teaching that matter emerges from mind. The premise of Experiential Realism is that the latter must be true: Despite our common human intuitions, Mind over Matter proves to be valid again and again in quantum physics experiments.

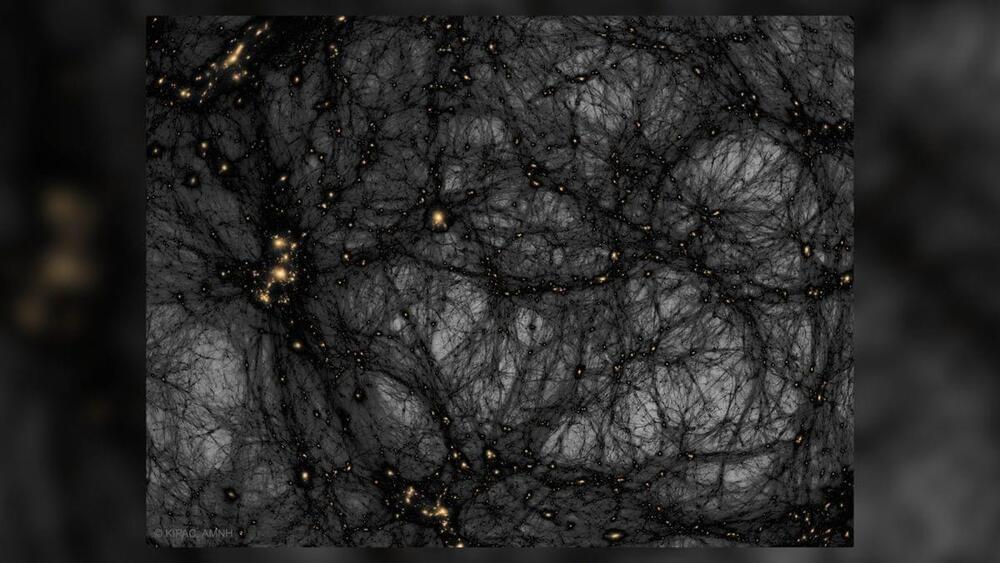

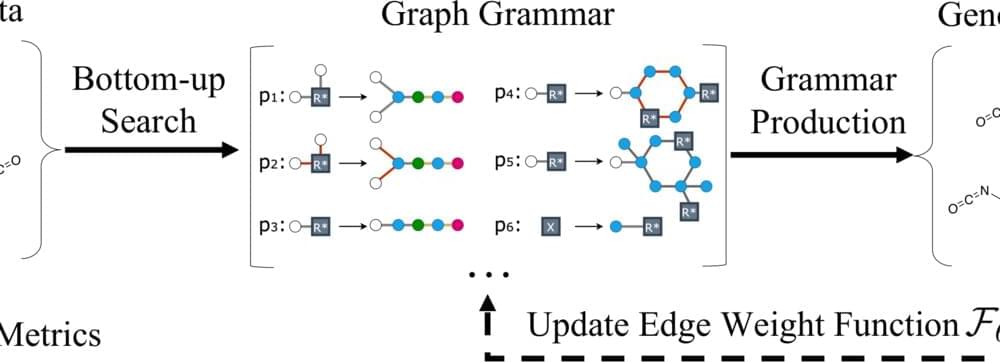

From the Digital Physics perspective, particles of matter are pixels, or voxels if you prefer, on the screen of our perception. Your Universe is in consciousness. And it’s a teleological process of unfolding patterns, evolution of your core self, ‘non-local’ consciousness instantiating into the phenomenal mind for the duration of a lifetime.