View insights.

0 post reach.

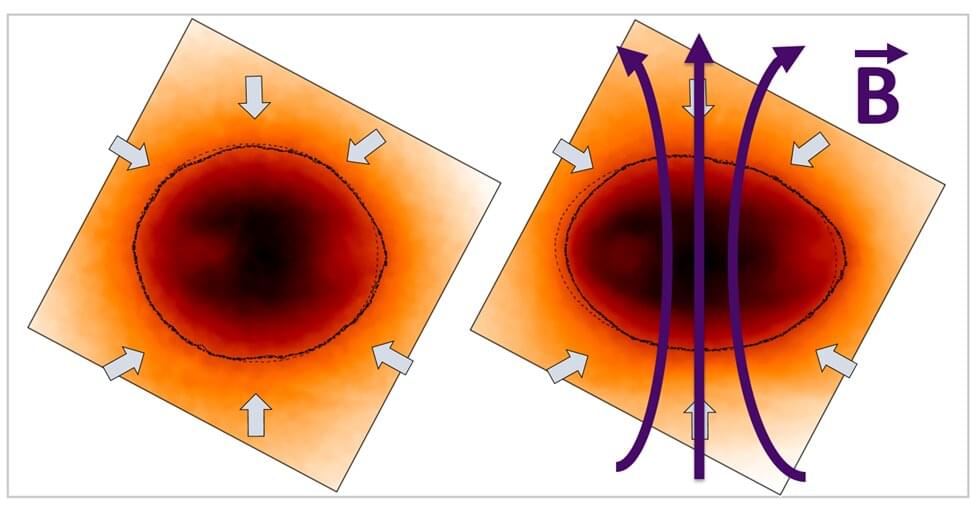

Noise in an electronic circuit is a nuisance that can scramble information or reduce a detector’s sensitivity. But noise also offers a way to learn about the microscopic quantum mechanisms at play in a material or device. By measuring a circuit’s “shot noise,” a form of white noise, researchers have previously shed light on conduction in quantum Hall and spintronic systems, for instance. Now, a collaboration led by Oren Tal at the Weizmann Institute of Science, Israel, and by Dvira Segal at the University of Toronto, Canada, has shown that an easier-to-measure form of noise, called “flicker noise,” can also be a powerful probe of quantum effects [1].

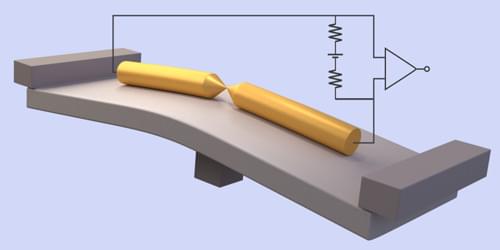

Flicker noise is a type of pink noise, whose spectrum is dominated by low frequencies—the kind of noise associated with light rainfall. Flicker noise also appears in electrical circuits, but its connection to microscopic transport channels remains poorly understood. To investigate this connection, the team studied an atomic-scale junction between two wires. They modeled the electrons passing through the junction as coherent quantum-mechanical waves that scatter off fluctuating defects located near the junction. These fluctuations can represent the trapping and releasing of electrons by static defects, the movement of charged impurities between lattice sites, and the fluctuations of atoms and molecules adsorbed on surfaces.

By comparing calculations with experiments on junctions with different parameters, the team showed that flicker noise can be connected to the number of quantum conduction channels and to the contributions of the individual channels to the overall conduction, providing similar information to shot noise. Since flicker-noise measurements are widely used, they could now be applied to shed light on quantum and many-body effects in a broad range of nanoscale electronic devices, the researchers say.